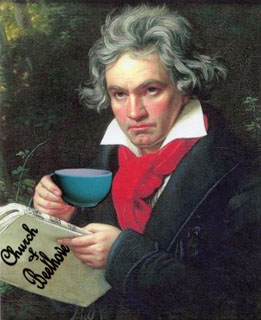

The Church of Beethoven: Fifth Street Praise

On almost any given Sunday, musical orthodoxy and a sometimes radical creationism reconcile, if not always harmoniously, inside the space of the Church of Beethoven. Both a physical place and a trope of musical devotion, the church, located in a 5th Street warehouse in Albuquerque aptly nicknamed the “Kosmos,” hosts some of the most consistently innovative and intellectually curious programming of contemporary music anywhere. Poets from Choctaw to slam read at every concert as well. It’s a kind of breakout moment of worship when, in the name of the god of the Moonlight and the Fifth, you can hear Massenet, Le Chat Lunatique, Steve Reich and SKUMBAG. There are, to be sure, plenty of eloquent offerings of Bach, Vivaldi, Ravel and Beethoven himself. You could say that true to its visionary founder, cellist Felix Vernum, who passed away in late 2009 after a courageous struggle with cancer, the church continues working out his musical unified field of everything. Consider a recent performance that included a blue grass, Dixieland style invention written for the Swiss Shoemaker’s Guild, and a string quartet composed by 16-year-old Celeste Lansing, who tore at the conventions of the form, reassembling them into a jagged, sometimes emotionally elegant 3-minute montage.

On almost any given Sunday, musical orthodoxy and a sometimes radical creationism reconcile, if not always harmoniously, inside the space of the Church of Beethoven. Both a physical place and a trope of musical devotion, the church, located in a 5th Street warehouse in Albuquerque aptly nicknamed the “Kosmos,” hosts some of the most consistently innovative and intellectually curious programming of contemporary music anywhere. Poets from Choctaw to slam read at every concert as well. It’s a kind of breakout moment of worship when, in the name of the god of the Moonlight and the Fifth, you can hear Massenet, Le Chat Lunatique, Steve Reich and SKUMBAG. There are, to be sure, plenty of eloquent offerings of Bach, Vivaldi, Ravel and Beethoven himself. You could say that true to its visionary founder, cellist Felix Vernum, who passed away in late 2009 after a courageous struggle with cancer, the church continues working out his musical unified field of everything. Consider a recent performance that included a blue grass, Dixieland style invention written for the Swiss Shoemaker’s Guild, and a string quartet composed by 16-year-old Celeste Lansing, who tore at the conventions of the form, reassembling them into a jagged, sometimes emotionally elegant 3-minute montage.

Lansing was a student at Whitehorse High when she composed “Pink Thunder” under the auspices of the Native American Composer Apprentice Project. (NACAP). The music is all about her exuberant, gifted experimentation with the possibilities of stringed instruments, the bow’s special effects and percussive tantrums, harmonics and scratches, the players’ deft conversations in a round of scale passages or hoofing chords. But it begins with one viola, one note, while a violin very slowly swings above it, seems to stop in mid-air, then resumes. There is a restless predatory texture that sets in, and an avian weirdness especially, in the progress of sudden trills, mewling, whines, and pizzicato. Some of the subsequent solo work conveys a beautifully realized lyrical solitude. Violinist David Felburg, the church’s co-artistic director and former colleague of Felix Vernum, led an exceptionally imaginative response to the score.

As part of the program’s spoken word, George Ann Gregory, poet and Fulbright Scholar, intoned hymns of the Choctaw and Cherokee sung to commemorate “The Trail of Tears,” their forced removal in the 1830s from Arkansas territory. Her unaccompanied voice, elemental, bare, and embered, wove a winter sorrow from indigenous pentatonic strands and traditional Christian melody. Her long historical narrative of Andrew Jackson’s betrayals, the tribal misery of a frozen Mississippi crossing, while delivered too prosaically, had the advantage of the warehouse’s natural morning light, worn, rose-colored brick and stained glass. The spacious, barreled ceiling was part Christian ark, part Native long house

How much music has been written for trombone and violin? It’s the kind of esoterica given a fantastical rendering by the Folk-Reimagined project, conceived and performed by the electro/acoustic duo of trombonist Steve Parker and violinist Molly Emerman. Their website page, with an almost deliberately droll text-message or AP wire brevity, suggests little of the project’s extravagance, its tropical electric musings on Boss Nova, or the kind of rapture and mischief in their Klezmer derivations. There’s slapstick virtuosity recalling a cattle auction along with heart-like pulsing out of digital delays and random time decays. Structurally sophisticated, technically demanding, the pieces, some commissioned by Parker himself, combine an assured, classical practice with folk’s soul and wit.

Avid Magahi’s “Parallel Worlds” for solo violin conjured Romanian dance, perhaps the liturgical voicings of the Ashkenazi. Emerman, who is 1st violin of the Austin Symphony, played impulsive and impetuous, making frequent trills and leaps.

The Schumascher Marsch written by Daniel Schnyder I already alluded to. Wildly contrapuntal but ever on the march, it’s a rousing tour de force in miniature. Think of Stephan Grappeli and a Dixie Land swing band of Zurich shoemakers chasing each other round through a Swiss Clock, while Parker’s trombone bass line periodically provides old sturdy baroque authority.

Perhaps the most digitally haunting, because of sensuous pre-recorded vocals and infectious rhythms of shakers, was Ian Dicke’s Musa. But the morning probably belonged to Steve Snowden’s “Ground Round,” a trombone and Macbook Pro collaboration that turned the Church of Beethoven into an auctioneer’s stall for Nebraskan cattle. Through both its pre-recorded effects and Parker’s considerable skill, we witnessed a Sunday transubstantiation of lowing cows, slow squealing gate hinges, and roaring trucks. I think I heard the knock of a gavel coming down to finalize a sale. Parker, currently an artist in residence at Austin’s Blanton Museum of Art, was at the center with an uncanny double-triple-flutter-tongued impersonation of the near unintelligible vocalizations of “Randy,” the world champ of cattle auctioneers. Here, “folk” re-imagined is not only a complex crossing of homely grass-fed tunefulness and modern antic anarchy. The recorded material takes the music into the realm of visual narrative, a brash Americana — not that different from Thomas Hart Benton — infused with the primary colors of place, work, dust and slaughter.