Alan Berliner’s First Cousin Once Removed: On Dementia and Poetry

Does poetry run deeper than perception?

Alan Berliner spent five years examining how Alzheimer’s disease closes down a poet’s creative life in First Cousin Once Removed. At the risk of making light of that affliction, this is a memorable film.

Edwin Honig Heads Toward the End in ‘First Cousin Once Removed’, by Alan Berliner

Always the narrator of personal stories, this time Berliner has connected with a dilemma that a generation faces with its parents (his mother’s cousin, in this case. The same generation dreads encountering it more personally farther down the road. It has a readymade public, and Berliner himself is part of it. His father also suffered from Alzheimer’s Disease.

As I said, Berliner’s films are nothing if not personal. But his relatives are closer to us all than you might think.

The doc, which premiered at the New York Film Festival, won the prize for Best Feature-Length Documentary at the International Documentary Festival Amsterdam. It will be aired on HBO in late 2013 – plenty of time for the film to play on theaters.

Exposure and awards on the festival circuit should position First Cousin for promising theatrical runs in English-speaking countries before its US cable date almost a year from now. Its affinities with Michael Haneke’s Amour –the wrenching Cannes-winning Alzheimers saga destined for more honors, including what should be an Oscar for Best Film — could help with showings beyond festivals internationally. Berliner, a veteran independent, has never been a bet for box-office – although critics have tended to be on his side — but raw honesty and improbable laughs make First Cousin his most commercial film.

The cousin in question is Edwin Honig (1919-2011), a poet, translator and once-eminent professor at Brown University. Honig’s memory and mind are trickling away. He can’t recall much, but what he says can come out as a quirky kind of poetry. Berliner forces viewers to wonder whether, in certain people, poetry is closer to the bone than consciousness. Don’t expect an answer from Honig, who makes blithe Delphic pronouncements on whatever reaches his psyche — like aging: “Prepare yourself, it’s worse than what you think.”

Not recognizing himself in a photograph, he declares, “I’m not impressed.” The laughs keep coming.

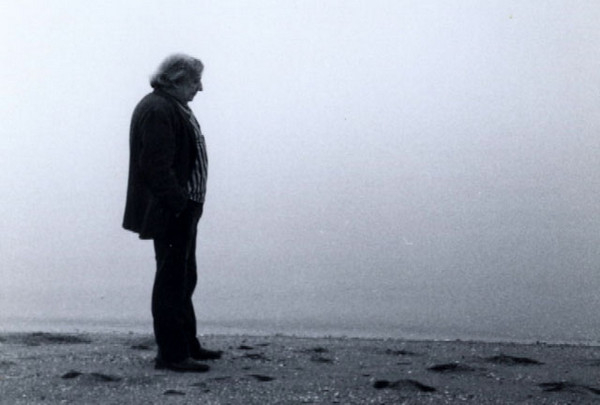

We accompany Berliner on visits to Honig’s residence, where the passage of time is reflected, often to magical effect, in the trees outside, which sprout leaves and shed them and sprout leaves again. Shifting among visits over five years, Berlin edits fragments with no impulse to give Honig’s illness a linear coherence, unless coherence is the inevitable deterioration of the mind that once made Honig the poet and scholar that he used to be.

In films like Intimate Stranger (1991) and Wide Awake (2007). Berliner crafted no-budget cinematic textures with typewritten text and still photographs – typewriter as percussion to a procession of black and white. Here he deploys the same pictorial language, this time drawn from Honig’s life and writings, but we watch as that structure eventually erodes and the flow of images oozes in and out of a kind of bluish mulch. Close-ups in chrystalline HD observe Honig’s unfocused eyes straying into a void beyond memory.

First Cousin Once Removed feels clinical at times, as Berliner tells the uncomprehending poet about his own memory lapses, expecting an answer that might show as much insight as Honig’s impromptu poetry. A special poignancy comes when it moves past the generic fatalism of Alzheimer’s into an individual’s life story. We see photos of Honig the translator being knighted by the prime minister of Portugal and the King of Spain. We also learn that Honig endured his father’s lifelong blame for the death of a younger brother who was hit by a truck. “I killed him” Honig tells Berliner bluntly.

Since Deborah Hoffman’s Notes of a Dutiful Daughter (1994), films about Alzheimer’s disease have tended to be stories of loss told by younger family members. Berliner’s story fits that mold, and it doesn’t. He’s not a son, which provides some distance from his subject, and Honig’s fading is a reality check on the boilerplate martyrology. There are those who won’t miss him. Two adopted sons, who lived with their adoptive mother when she left the eminent Honig, tell of his vicious cruelty honed by practicing criticism for decades, a grim case of art transforming life.

Not all the suffering in First Cousin Once Removed has its origin in a disease, but as Edwin Honig fades away there’s not much remedy for any of it.