CU Art Museum Sends “Through Soviet Jewish Eyes” To New York

The image is horrific. Dozens of men lie dead in a barren, muddy landscape. A silver, snow-filled trench winds off into the distance and dark clouds texturize the sky above. A woman in a heavy coat wails over a body in the foreground. Another women to the left is bent over, head hanging, body curling above another slaughtered man or boy. The photograph is called “Grief” and was taken in January 1942 in Kerch, Crimea (Ukraine) by Dmitrii Baltermants. Seven months after Germans invaded the Soviet Union. It was a news photograph that circulated widely in the Soviet press throughout that year and Soviet wire services sent the image around the world. But fearing it was propaganda; few news outlets picked it up.

It was not propaganda.

“Grief” is an image that captures the scope of human loss in the Soviet Union during WWII. Baltermants arrived at a trench on the outskirts of Kerch; days after the Soviet Army recaptured the city on December 30, 1941. (It would be re-occupied by the Germans in 1942). Older women and families were wandering, weeping and searching among dozens of corpses of civilians who it appears had been brought out into a field and shot en masse by the Einsatzgruppen (German army mobile killing units). The numbers vary, but it is estimated that the Einsatzgruppen killed 1.5 million Jewish men, women and children in the occupied Soviet territories in mass shootings.

Baltermants was one of the first photographers to document the discovery of Nazi atrocity sites, three years before better-known photographers Margaret Bourke-White and Lee Miller chronicled the liberation of German death camps. His photographs are on view in “Through Soviet Jewish Eyes: Photography, War and the Holocaust,” at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City.

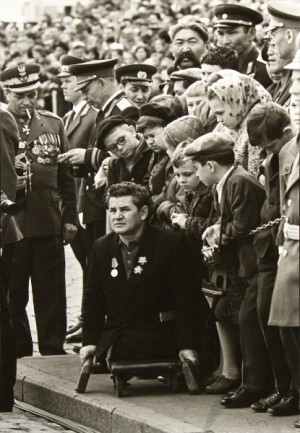

Based on David Shneer’s book Through Soviet Jewish Eyes, the exhibition presents more than 50 images seen through the lens of Soviet photojournalists, the majority of whom were Jewish. (Shneer is director of Jewish Studies at the University of Colorado, Boulder) and this exhibition debuted at the CU Art Museum in September 2011 and features other important Soviet photojournalists: Evgenii Khaldei and Georgii Zelma.

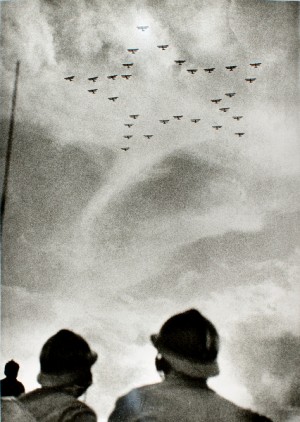

There is a striking duality in the images taken by these photographers. They include elements of Soviet agitprop, in the tradition of socialist realism, glorifying the Red Army and its patriotic soldiers and the nurses doing good work on the home front. On the other hand, these are Jewish photographers documenting the corpses of Jews and other civilians for Yiddish-language newspapers as well. Yet, according to Shneer, they survived by denying their heritage and few of the photojournalists ever embraced their patrimony, refusing to be buried in Jewish cemetery, learn Hebrew or leave for Israel. Their Soviet patriotism and survival came first. Shneer’s book and the exhibition, (which he curated along with Louis P. Singer, Professor of History at the University of Colorado, Boulder and Lisa Tamiris Becker, Director of the CU Art Museum) utilizes often unseen photographs to tell a story far different from the often-repeated claim that the Soviet Union tried to cover up Nazi atrocities. This exhibition shows that this idea is not only untrue, but that many of the photojournalists of the time were in fact Jewish and kept the violence against Jews on the front page of Soviet newspapers like Pravda.

The opening section of the show contextualizes the photographs within Constructivist and Socialist Realist traditions of Soviet photography in the 1920s and 1930s by including archival materials such as contact sheets, glass negatives, scrapbooks, diaries, Soviet publications and personal book maquettes created by the photographers.

The prints made by these photographers were often no larger than an index card, taken with beat up cameras, but with incredible skill, arranging light and form in a way that puts most landscape photographers to shame. On view are canonical images side-by-side with photographs that have not been widely exhibited. The images are printed in various sizes, with the larger-scale photographs blurring the line between fine art and photojournalism and challenging viewers to question contemporary societies interest in viewing these works in ever-larger scale. In many of these images, documenting horrific events merged with avant-garde modernist sensibilities to create an aesthetic that continues to echo across time— powerful and aesthetically compelling images of war.

Through Soviet Jewish Eyes: Photography, War and the Holocaust will be on view at the Museum of Jewish Heritage from Nov. 16 2012 to April 7, 2013. It will then travel to the Holocaust Museum Houston, Houston, Texas, and finally to the Paul and Lulu Hilliard University Art Museum, University of Louisiana at Lafayette.