Installation view of Urban Untitled

Urban Untitled Opens Capriccio Foundation in Santa Fe

Fabrication and myth-busting about making and its categories, all are part of the refreshing “Urban Untitled,” the inaugural show of a former private gallery space turned nonprofit, Capriccio Foundation for Modern and Contemporary Art (at 333 Montezuma in Santa Fe, with gallery hours.)

Four artists’ works are included: David McDonald, whose compositions of forms from found to handled track a certain distance toward the abject (heimlichkeit rips my flesh). Sarah Vanderlip has the fewest works in the show by number; her material choice of Mylar and paper backing is presented as bearing on the Japanese movement called “Mono Ha.” (More in a second.) Rebekah Potter who recently moved to Albuquerque, offers up stitched work that runs a risk in only one case of becoming so close a compare to Mike Kelley that her originality could be overlooked. Finally comes Drew Dominick, from whom the curator selected two disparate bodies of work, one of drawings on Plexiglas made by a grinder. The result: mandala shapes that resemble feather or lace. The second is “After Remington,” a body of constructed and also disturbing wrangles of cowboys and bull riders into expressionist torques that make you laugh – and simultaneously suspect the impulse.

As I contemplated David McDonald’s row of small objects, I found myself wanting to describe closely the there: tongue-shaped clay with a tiny gilded ball extruding; a four-deep pile of irregular painted wood slices with the color red forging capital E expression from out the blond of wood; and, my favorite, wax tranches, against which wedged pinky-white cubes looked as if the artist model-made a Philip Guston detail.

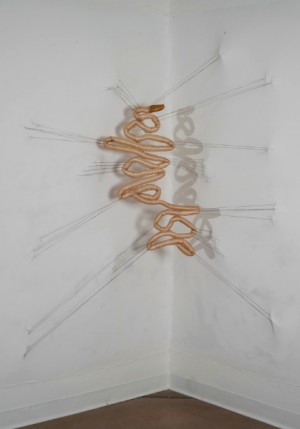

Next to McDonald’s shelf, is Rebekah Potter’s sewn snakey object knotted fast to its own convex surround. The “What Could Not Be Contained” coil is red; on the catty-corner wall across the gallery is its golden twin, with the evocative title, “Golden Tip for Fighting the Little People: Guts Wield Power.” The Little People are a Haruki Murakami joint; part of the contemporary dystopic myth that is 1Q1984, and are proving a very sexy idea for visual artists representing a far-out literary idea.

Bruce Brosnan's Air Chrysalis, shown at Feature in NY in March 2012

I happened to see at Feature Gallery in New York in March, another riff on 1Q84, in Bruce Brosnan’s Air Chrysalis which the gallery explained, quite aptly, as “mostly object and very little ground.” The same can be said of Rebekah Potter’s work.

Much more problematic for me in this show was Sarah Vanderlip’s work, titled, rather ponderously, “Drawing for Sculptures of Buildings #46 (After Tony Smith),” and “”””#48, #40, #41.” Apart from a titling convention which closely owes to (yes, of course), minimalism, the work itself has the feeling of having required something closer to an untouched surface than what it arrived at.

Much more problematic for me in this show was Sarah Vanderlip’s work, titled, rather ponderously, “Drawing for Sculptures of Buildings #46 (After Tony Smith),” and “”””#48, #40, #41.” Apart from a titling convention which closely owes to (yes, of course), minimalism, the work itself has the feeling of having required something closer to an untouched surface than what it arrived at.

Mylar being a particularly tricky material, which is puffy (think balloons) if filled up with air, physically pliant if not compliant, Vanderlip’s jousts with it are in the manner of something not mastered either for its incompletion or its finish. To install it she grounds it on paper backing but if the drawing for the structure is meant to show a model, in which parts are synthetic with one another, it’s a fault either of installation or fabrication that what is evident are small ways in which the material just finally wouldn’t cooperate.

Enter the reference to Mono-Ha, which was a movement of Japan late 1960s and ’70s, in which eliminating the act of making, the unrepresentable physicality of the earth, were its manifestos. Also, “contemptuous indifference” chalked its agitprop, if indifference can be equated with agitprop.

You see the problem. You can’t be “After Tony Smith” and also be “After Mono Ha.” So the trouble with this work is your eye goes to its flaw. Something not resolved between idea and making.

I had a similar issue, with Drew Dominick’s grinder drawings on Plexiglas. For a strategy of multiples and a strategy of repetition has to answer something about why also a strategy of frame? In order to show different sizes?

On the other hand, I greatly liked the “After Remington” sculptures, in which the material choices from leather to suede to chewing tobacco to wire made for torqued spirals, the Baroque gone absurd into a fractured fairy tale.

Individual issues aside, this show manifests a high point for Santa Fe in its experiment and sense of the lightness of making. Foundation (former gallery) director Tom Tavelli, who has a show of Gee’s Bend quilts on view now at the 222 Shelby Street location that is effectively a sister space of this new home to Capriccio Foundation, clearly looked hard at surfaces and issues of making from quilting to composing to contemptuously or indifferently proposing art’s rearrangement of how we see utility in materials and form.