The Light Years: James Turrell’s Retrospective at LACMA

Nearly 50 years of James Turrell’s holograms and geometries of light comprise the restless and revelatory retrospective at LACMA now through April 6, 2014. The comprehensive L.A. exhibition follows on the artist’s return to east-coast prominence at New York’s Guggenheim this summer after a 33-year gap. In its humming intensities, trompe l’oeil effects, and liminal atmospheres, Turrell’s work re-enchants perception: light returns as a pure object of contemplation.

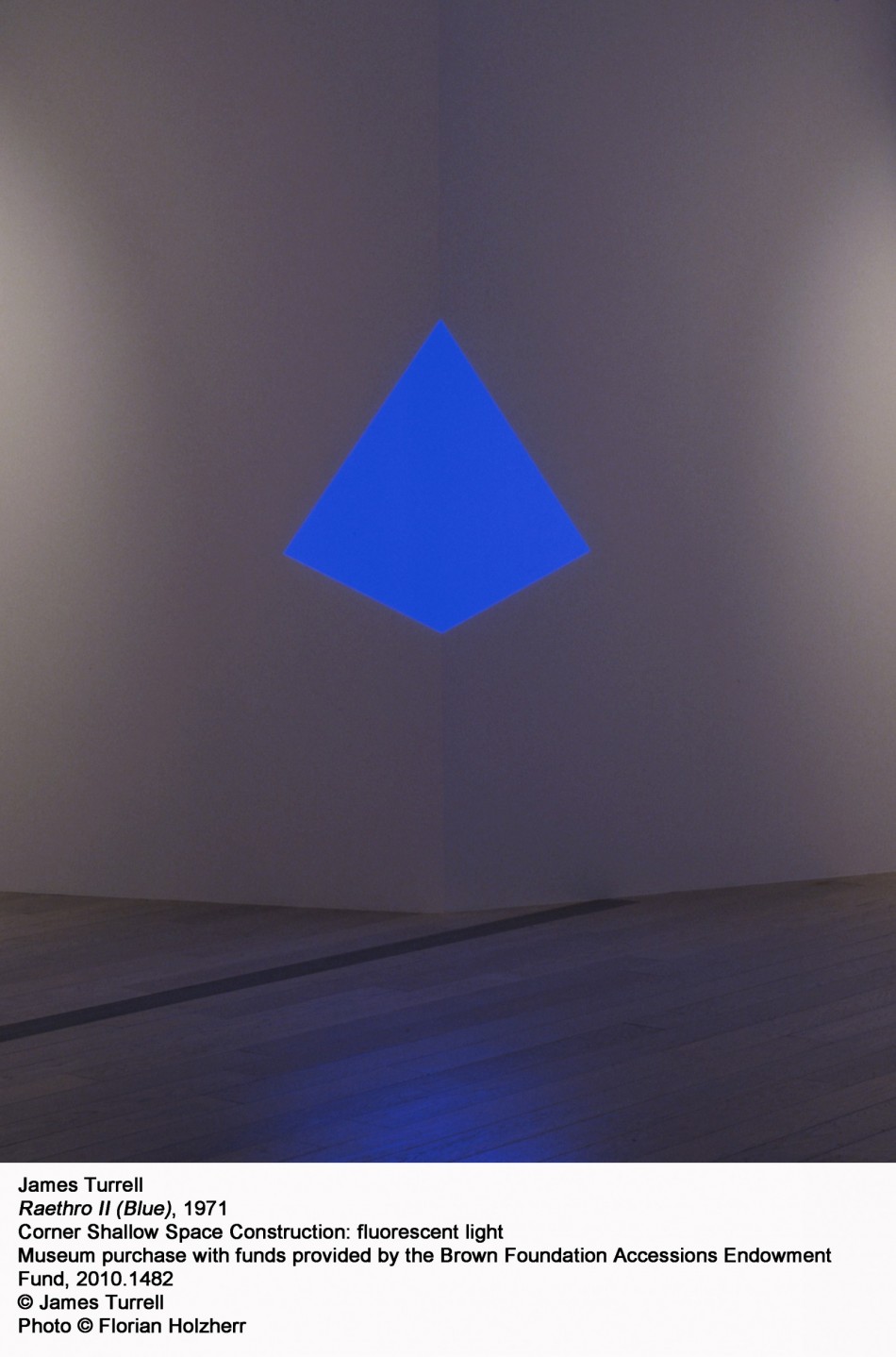

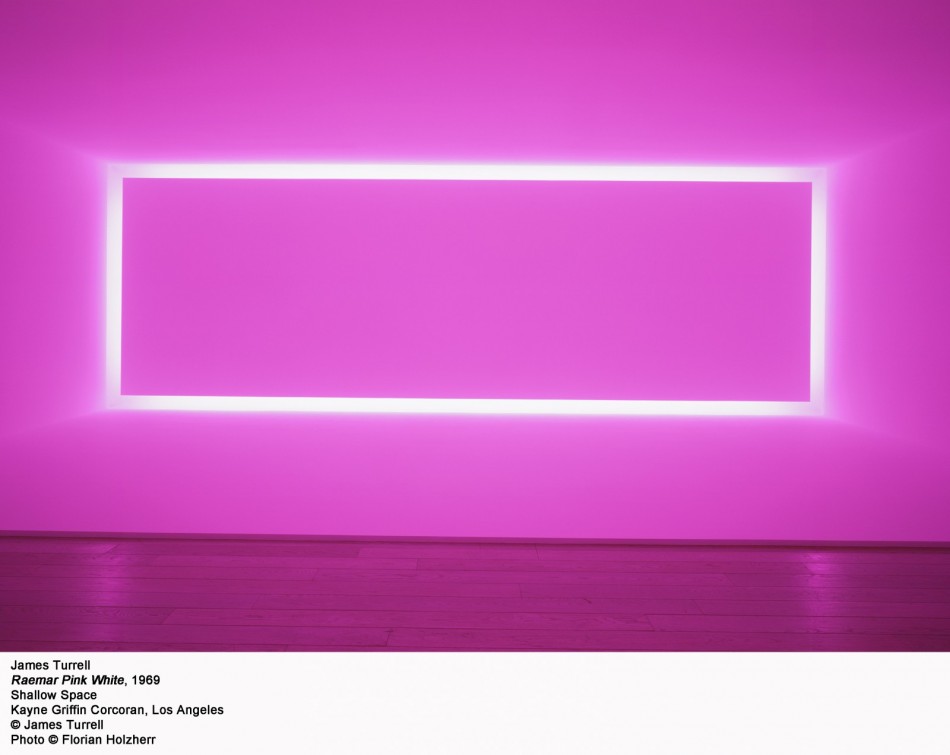

Of course, Turrell’s is also a manufactured light. LED technologies, ambitious environmental designs, fluorescent colors from lurid magenta to watery blue refer us back to the urban lightscape outside the museum. There perception encounters itself anew in the arresting singularity of a neon sign, or the complex play of light and reflection which, in a window pane, can evoke Turrell’s own mirrored holograms, also hanging in a separate gallery of the exhibit. “Raethro II Blue,” a sky-blue pyramid with a skitzy vibe, floats like a shard of commercial lighting in the corner of a bruised pastel wall. The massive plane of “Raemar Pink White,” brazen as glowing lipstick, glamorizes its own spiritual territory. Turrell conjures some of the wonder that must have been felt when light became an “invention,” a second Promethean theft that electrified into a light bulb the old optics of fire and sunlight.

To be in the same room with “St. Elmo’s Light,” a large rectangular inset of violet lighting flanked on each adjacent wall by soft small ovals of eggshell light, is to approach Turrell’s “experience of wordless thought.” Turrell, a California native with a degree in perceptual psychology, characterizes this quality as “the thingness of light itself.” Paint, even in the grandeur of Turner or Bierstadt, confines light to canvas. But St. Elmo’s three-dimensional vibrancy is everywhere — and not quite anywhere — transfixing with cerebral immediacy. “Wordless thought,” yes. Still, St. Elmo’s is light about light, the storied weather phenomenon known as St. Elmo’s fire: luminous discharges of plasma flaring from the tops of ship masts or the ends of airplane wings. Sailors once held the light in mystic regard. In this installation, Turrell, at one time a reconnaissance pilot, creates a sense of unearthly, violet altitudes: color without horizon.

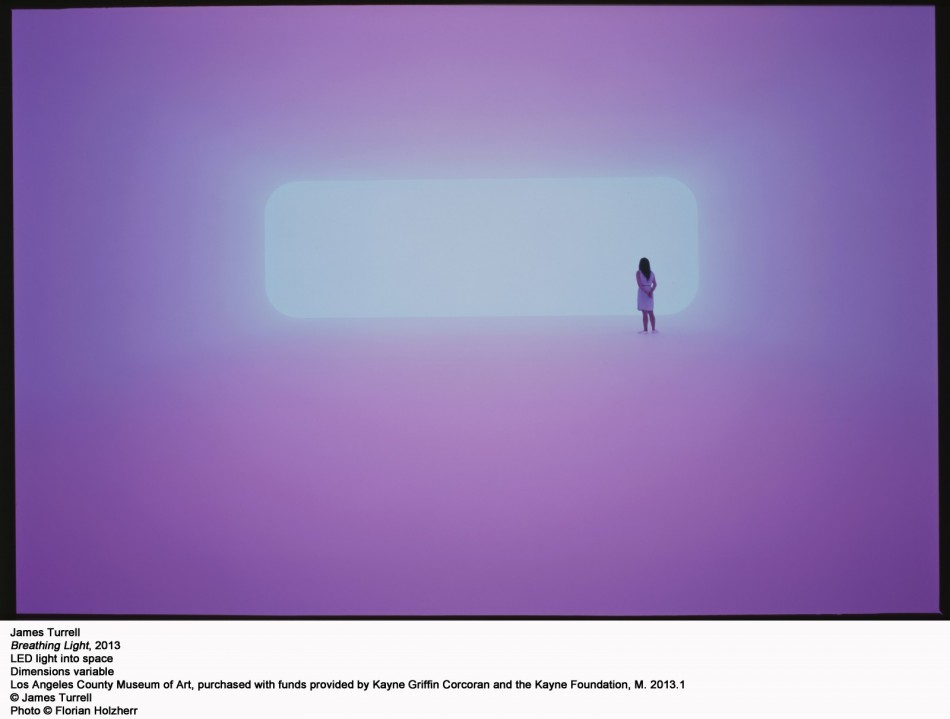

In the eloquent enclosure of “Light Breathing,” a viewer passes from a dramatic black-carpeted stairway through a square opening into a gently sloping world without edges: glacial quietude, slow metamorphic oscillations of magenta, pink, sky blue and aqua on the front wall beguile perception. Yet when “seeing” with the whole body, every step a slow breathing, the space suggests a funhouse of tilted floors and opalescent mist. You put up your hands to find the where of things. The entrance is now itself a thin square wafer of disquieting umber light beyond which human silhouettes mill about. We on the inside tend to pause, posed like strikingly realistic figures mannequined within Turrell’s installation.

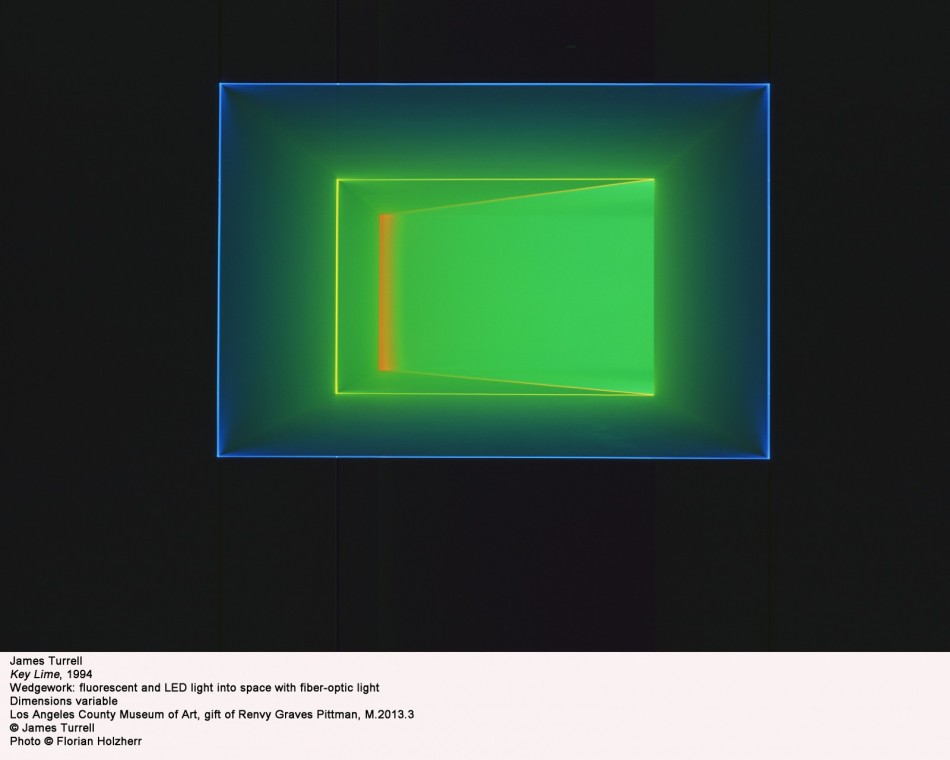

“Key Lime,” the most alluring architecturally, looks as if Turrell, with a yellow trapezoid and a yellow and blue receding rectangle, had left a door intriguingly ajar at the back of a luminous room, causing an entire long wall of glowing lime to swing open from its wide yellow frame. The effect is enhanced by the dark recess in which the installation is staged, a space made more odd and psychological by the differing lengths of the walls as they recede asymmetrically into the distance. “Key Lime” keeps much of its muted vibrancy to itself so that the viewer remains in near-total darkness. Turrell puts us in a black box theater, looking both into and inward, the three-dimensionality drawing us to the back of our own mind. The door of perception or an exit? Either way there seems nothing at all beyond.

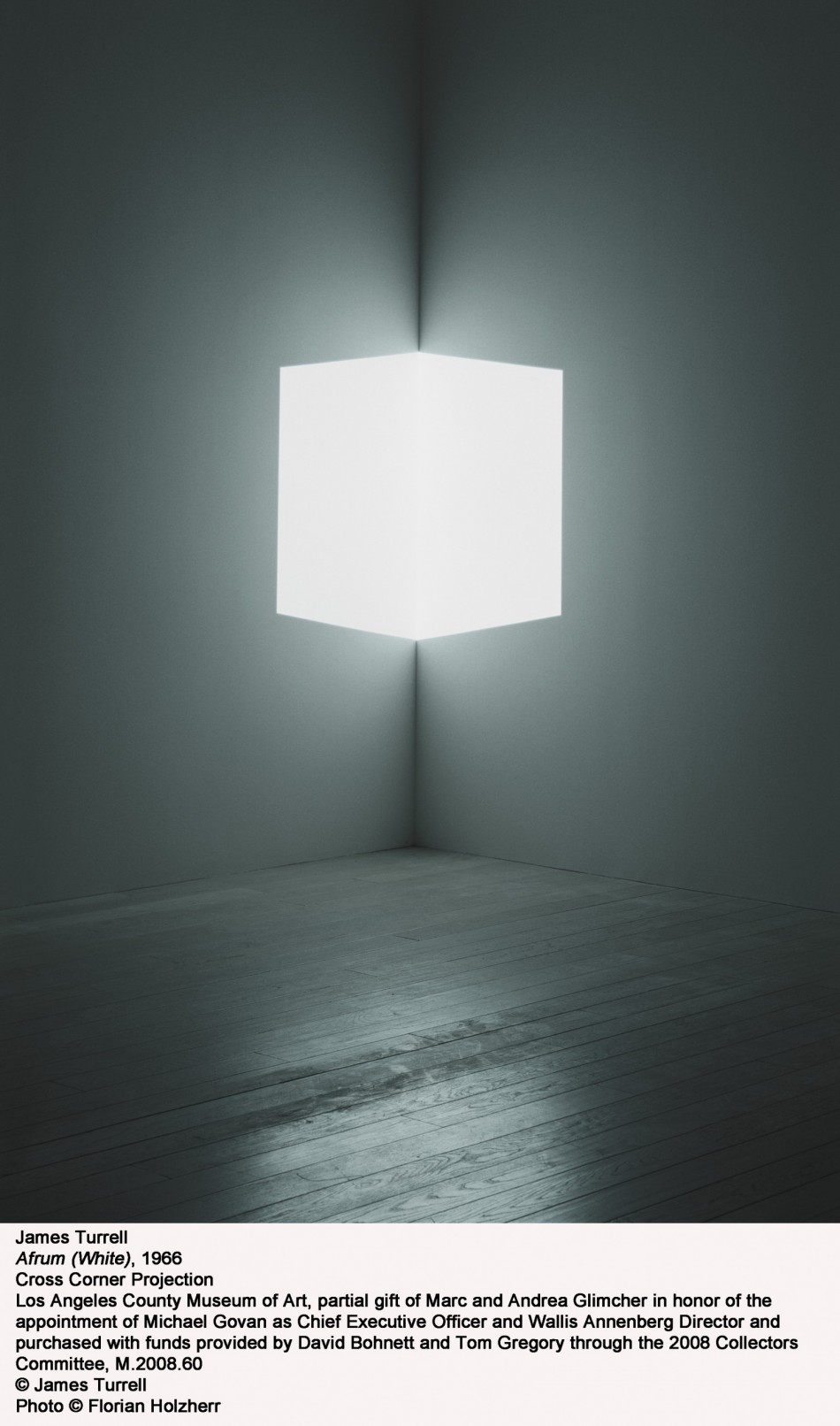

There is no catalogue entry, no title, for the most subtly pervasive of exhibits: the “accidental” reflected light from the installations themselves that stain us pink or glow along a corridor. The whiteness from “Afrum White,” seemingly so confined in a delusional cube, wanders the adjacent sheet rock.

Turrell’s accurate and visionary choreography can only control light’s fundamentally nomadic nature so far. In the end, light finds a way back to its work of lighting and coloring other things. Standing before the candied three-dimensionality of “Juke,” a fluorescent green trapezoid, I watch how its luminescence, like the sustained pedaled tones of a piano, drifts away from itself, washing the far emergency doors with a spiritual lime. Above it the green word EXIT, more itself than ever, becomes an invitation into the bright daylight of L.A.