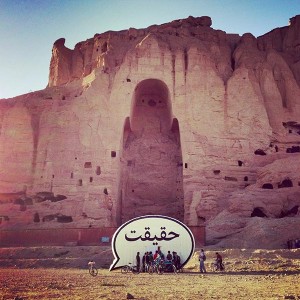

Truth Booth 9 Jim Ricks Meri Herawi Girls School, Heart, Afghanistan

On a Truth Quest in Afghanistan

The equivalent word for truth in Dari is: حقیقت.

Dari and Pashto are the primary languages spoken in Afghanistan, where the interactive work of public art In Search of the Truth (The Truth Booth), by Cause Collective artists Ryan Alexiev, Jim Ricks and Hank Willis Thomas, recently toured. Yes. A work of public art by American artists living in San Francisco, Dublin and Paris, just returned from a two-month-long experience in Afghanistan. In partnership with the leading Afghan television station 1TV and Free Press Unlimited, the giant inflatable cartoon speech bubble, with the word حقیقت boldly printed on the side, houses a video recording booth. Afghans were asked to consider the question, “What is Truth?” and record their reaction to the statement, “The truth is…” in two minutes or less. Two minutes to define truth in a country that has been war-torn for 30 years, its people without a voice.

Ryan, Jim and Hank, who met via the California College of Art where each earned an MFA, became aware of the diverse meanings of the word, truth, while developing an earlier project in 2006, The Truth is I am You, that became a permanent installation at the University of California San Francisco. They utilized 24 native languages, representing the student population at UCSF, to display a single line from a poem written by Ryan and Hank called The truth is…. Translating the poem into so many languages proved challenging.

“The word Truth, with a capital T, is so difficult to translate and difficult to explain,” Ryan says. “This notion of the ‘truth’ became an interesting thing. We even began to wonder if it was a platonic Western concept that doesn’t exist in other cultures.” So rather than tell people what they thought was truth, Ryan, Jim and Hank decided to ask others that question, to determine if the truth was “out there” somewhere.

They conceived the idea for an inflatable sculpture that was also a recording booth and imagined taking it all over the world to remote jungles and urban city centers. They secured funding from the Arts Council of Ireland and the San Francisco Foundation, launching The Truth Booth at the Galway Arts Festival in 2011. From there The Truth Booth went to various venues throughout Ireland, including the National Ploughing Championship, The Lisdoonvarna Matchmaking Festival and Belfast Culture Night, recording more than 2,000 videos. A common response was “there is no Truth.”

In Afghanistan, things were different.

“In general they loved it,” Ryan says. “All of sudden they had a chance to get out there and say something and be heard. It was a breakthrough thing.”

They set up The Truth Booth in Bamiyan, in the space formerly holding one of the Buddhas which were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001 and in a potato field. It was inflated near the Mosque of Ali (Mazar-i-sharif) and the Shrine of Ali, Muhammad’s son-in-law and cousin. At Lake Qargha it was reflected in the water. In Kabul, the whiteness of the sculpture stood out against the artificial turf that covers the blood soaked ground at Ghazi Stadium where the Taliban executed, stoned and mutilated citizens.

The Afghan responses were never subjective or philosophical. Ryan and Jim both surmise that this is because of the nuances of translation. They didn’t realize how difficult it would be to get translations from Pashto and Dari into English or vice versa. Part of the problem is the level of literacy in Afghanistan. Few people can write. It’s one thing to get the meaning verbally; it’s another to write it down and have that same meaning expressed. Translations of the video recordings are proving particularly challenging because the people intermix their languages and speak very quickly, especially the women and girls who, it appears, are trying to say as much as they can before someone silences them.

“As the tour went on, we discovered that the word Truth in Pashto or Dari is synonymous with fact or reality,” Jim says. “It means something different and has a more practical application.”

Yet the Afghan responses are indelibly human, whether it was a young man who spoke in English, saying he was stung by a scorpion, it really hurt and took him almost 20 hours to recover, or a boy who complained about the price and quality of cell phones. One girl at the Mehri Herawi girl’s school in Herat, with large green eyes, her head and face fully covered in black, spoke clearly and powerfully, saying:

The Truth is I’m proud to be Afghan. And I’m proud of my nationality, but our problem is that being Afghan is not enough. Everybody is trying to get ahead and make some money. No one is paying attention to the youth or the country. No one cares. No one cares about our education, success and development. Everyone wants us to remain backward. No one cares about us. No one tries. No one wants Afghanistan to be known. The problem is they only think about themselves and getting ahead and making money. They don’t want to solve the problems. No one is thinking about our security. No one is thinking about the children’s future. No one cares about the children. Every year many children die from diseases, violence, kidnapping and abduction. They don’t want to think about these things.

Another poignant contribution came from an old man who said, “I am sick right now. I have eight children. We are farmers. All my income goes to feed my children. We have no other income. I was a governor in my life. I worked for twenty years. Then I retired. I have received my pension for four years. We have no other income.” He stopped speaking, his head seemed to tremble and quake, and he was breathing heavily.

“That is his truth and it is real,” Ryan says. “You feel total empathy. It’s a profound insight into rural Afghanistan in one minute.”

An insight that very few have—if anyone—and governments need.