San Siro showed at TIFF's Wavelengths 3

Wavelengths at TIFF: Grand Shorts Tell Epic Stories

The Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) was mass urbanism once again this year, as closed streets formed a public mall that seemed like a treadmill, a continuous loop of Hollywood stars. In the Wavelengths section at TIFF, shorts outnumbered features four to one and commercial potential was barely an afterthought. Nor was the Oscar-mongering obvious, for which TIFF’s opening night now seems to be the starting pistol.

Much at Wavelengths was from Cannes or Locarno, but the audience that discovered the films at TIFF wasn’t complaining. These films will be opening in theaters over the next six months, if they open at all.

“The themes that were really speaking to me were nationhood, contested territories, loss of language, oral histories, speculative histories,” said Andrea Picard, who programmed the series and curated the collaboration between TIFF and the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art. “It’s a real reflection of what’s going on in the world today: What are we losing, what are we gaining?”

Embattled States

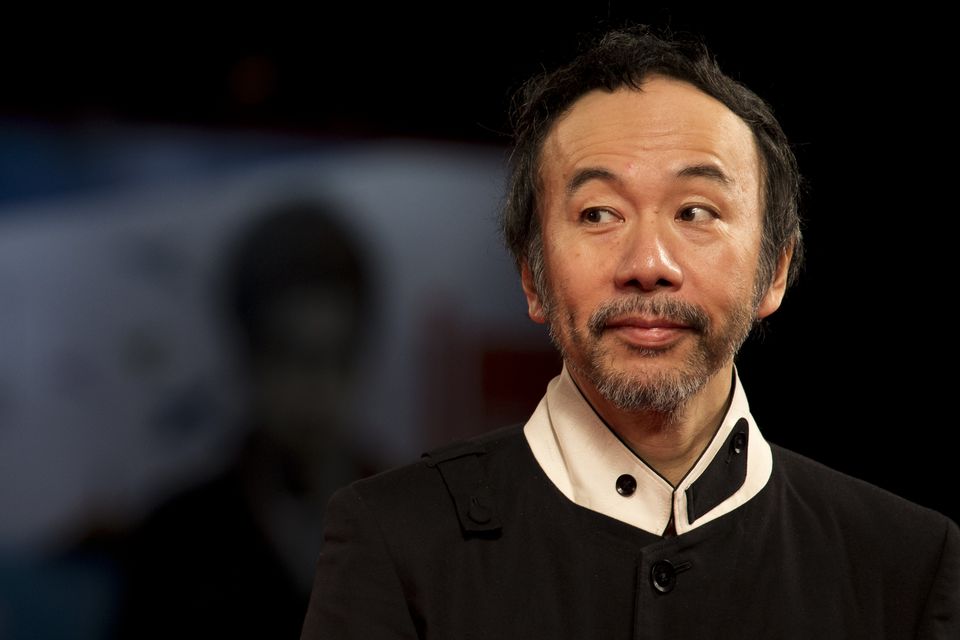

Loss of honor was there in epic scale in “Fires on the Plain,” Shinya Tsukamoto’s Venice-winning remake of Kon Ichikawa’s notorious 1959 war classic of a broken Japanese army in retreat, stumbling up a ridge toward a ship scheduled to take soldiers back to what they think will be safety in Japan. Between the filth-encrusted troops and that vessel are thick jungle, vengeful Philippine guerrillas, Americans with technology — and nothing to eat but each other. A scandal in 1959, it is controversial again; the metaphor of national defeat has never been so tactile.

Tsukamoto’s World War II saga violates the Japanese taboo on depicting the army in a dishonorable manner – and things rarely get more vividly dishonorable than what we see on the screen. With food scarce and foreigners (whom the Japanese invaded and enslaved) gunning for them, civilization breaks down. So much for esprit de corps.

Ukraine, that part of Europe where World War II came close to the savagery of the Pacific theater, is at the tipping point in “Maïdan,” Sergei Loznitsa’s vast panoramic of the Ukrainian revolution before the Russians piled in. This historical lens draws from two ends of the spectrum. Loznitsa’s approach, setting up enormous shots — in the spirit of Eisenstein — that observe thousands of characters, aligns with classic history painting. You tend not to see so much of that painting done these days unless you’re in North Korea, or in the Mormon Church.

Religious painting has the same vast historical perspective. Lech Majewski reached for it in “The Mill and the Cross” (2011), his evocation of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting, “The Road to Calvary” (1564).

Loznitsa frames the ebb and flow of battles on the square between forces of order and protesters. He finds common ground with Bruegel and Majewski in his inclusion of the grandest and the most ordinary of things: crucifixions, making tea, serving food, or walking to and from work.

It’s all in that frame. Like Bruegel, who witnessed the brutal Spanish occupation of the Low Countries, Loznitsa knows that life can go on in the most extreme of circumstances. All it takes is looking, and his gaze measures up to that overused description, painterly. Maïdan is a magnificent series of tableaux vivants. “For me that was a riposte to the handheld coverage of the Occupy movement,” Picard said.

Director Shinya Tsukamoto

Political Perspectives

From epic battles, we move to a more intimate look at politics. “Letters to Max,” the quirky epistolary documentary by Eric Baudelaire, is the filmmaker’s correspondence with Max Gvinjia, the former foreign minister of Abkhazia, a mini-state that broke away from Georgia in 1992. In the letters, you’ll sense the damaged status of a nation orphaned in infancy. As the new nation searches for legitimacy, you’ll begin to wonder about that concept. Abkhazia broke off from the Republic of Georgia, which itself had been denied sovereignty for decades by the Soviet Union, and the most powerful champion of the national autonomy and territorial integrity of Abkhazia is none other than Russia, which is violating the sovereignty of Ukraine as we watch.

Confusing? Of course it is, as Baudelaire knew it would be, and the odd daily drudgery of running a tiny nation seeps into the letters. So does humor. In a stroke of luck, an official delegation from Abkhazia is invited to visit Nicaragua, one of the few countries to recognize it. Gvinjia is thrilled, especially when their chartered plane stops to refuel in Cuba, another fraternal nation. But making friends means staying an extra day, with a leased jet stuffed with Abkhazian wine and musicians, but no food. “How do I feed these people, and with what money,” the diplomat wonders in a panic. I can just see Mike Myers in the feature remake. Who would have thought that a Wavelengths film might have such potential?

North Korea intersects with Wavelengths not just for its retardataire practice of 21st-century history painting. “Songs from the North,” the first feature by U.S.-based Soon-Mi Yoo, takes an approach akin to Sergei Loznitsa’s in “Maïdan”: just roll the camera. Of course, that’s usually a crime in North Korea, and the parts of the country that foreigners see are already confected dioramas. Yoo explores these convections, one song at a time. We hear the actual voice of Kim Il-Sung, a low grating squawk, singing a song that led the Japanese occupiers to call off their siege in World War II — nothing if not a miracle.

With the right archival images, legends of North Korea can be instant screen kitsch. We have plenty of self-parody here, but we also have missile tests and North Koreans who are afraid to talk about anything. Could “Forbidden Planet” be a better title? Only if it had a theme song. Yoo’s pageantry in her personal North Korea 1.0 blends fantasy with our own horror of the place.

The Architectural Canvas

Another pilgrimage to the antipodes is “Provenance,” by Amie Siegel, a current success story of the experimental film/art set. (The video, shown for free in TIFF’s collaboration with the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art, was also bought by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it is on view in New York through January 5.) We start in Chandigarh, India, where Le Corbusier and his team built modernist works outside the modernist belt. We follow the chairs designed for those Chandigarh buildings — in situ, then to England, and eventually to an auction at Christie’s.

Art doesn’t simply follow capital in “Provenance”; it is capital in this journey of the chair back to where the big banks are. Yet in the course of that journey, evoking Heinz Emigholz’s rigorous silent observations of architecture, the human overlay in Chandigarh stays with you. (The Emigholz parallel is his remarkable 2012 “Perret in France and Algeria,” in which a cathedral, built by Auguste Perret in Oran in 1912, is now a public library.) In Chandigarh, hundreds of chairs are stored in stacks — “don’t the Indians know how valuable they are?” a dealer might ask.

Architecture is at the core of “La Sapienza,” one of TIFF 2014’s great pleasures, by the American ex-pat Parisian Eugène Green. A confrontation between the scourge of over-building (also evident in Toronto) and the refinement of an architecture rooted in history — what can be more historical than Francesco Borromini’s church of Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza in Rome? — the film unfolds like an 18th-century philosophical dialogue. Its mannered style of argument echoes Diderot or the French dramatist Pierre de Marivaux, along with the emotional detachment of early French New Wave cinema and a dose of Whit Stillman’s whimsically urbane pessimism.

“Sapienza” is a word connoting a deeper human quality than wisdom. Green’s camera occupies Borromini’s church. Characters ask how architecture can be practiced, given the appalling quality of so much of the built landscape; through Borromini’s legacy, Green finds hope.

In Toronto, looking out his hotel window at a grim forest of high-rise condo-clones, Green said that he experienced “love at first sight” for Borromini. It’s the other extreme from Jean-Luc Godard’s fragmented nihilism in “Goodbye to Language,” which could have been in Wavelengths, but for Godard’s exalted Master status. And there’s more good news for “La Sapienza,” which is at NYFF; it will get a commercial release from Kino Lorber.

The clever short “San Siro,” by Yuri Ancarani, who trained as an architectural photographer, takes you into the enormous soccer (“football”) stadium of Milan. The homage here is to the robotic medical camera, which toured inner human organs in Ancarani’s remarkable “Da Vinci” (2012). Ancarani isn’t celebrating a noted architect in “San Siro,” where no one speaks, nor is he following sports fans through the vast building where flocks of birds are dispersed by gunshots. He puts you inside a massive machine, designed to contain Italy’s most ardent passion — not love, but football.

The stadium isn’t Borromini, but San Siro has its own utilitarian architectural distinction: circulating people like a refined work of plumbing. As cinema, the film has a serene, surgical precision.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=QUigVWY5tNk

La Sapienza was one of the festival’s great pleasures

Hope on the Cinematic Landscape

Like Green, Ancarani struggles to acquire production budgets. Italy has no theatrical doc circuit and few television outlets. Into the breach comes the biennial and art world circuit, where Ancarani finds spectators and Picard now finds half of her films. Shorts, always a poor relation, have an advantage because they suit gallery venues.

Ancarani next travels from TIFF to, of all places, Hollywood — or at least nearby. His first solo U.S. museum exhibition opened at the Hammer Museum at UCLA on September 27.

The many Wavelengths roads this year point toward the program’s primus inter pares, Pedro Costa’s “Horse Money” — a mix of tortured stories, betrayed hopes and grand cinematic ambition, told in fragments, at a low budget. If not a leader, Costa is a role model in his sheer staying power. His film, also at NYFF, is a bona fide succès d’estime.

So are other titles at Wavelengths, like “Fires on the Plain,” “La Sapienza,” and “Letters to Max.” For Eugène Green, who chases money and disappearing cinephiles, Toronto showed him that he wasn’t alone. “They’re not doing the same things as I am, but there’s a certain bond, an affinity. I can tell myself that all isn’t lost. That keeps me going.”