Michael Cook, Died of A Theory

Michael Cook Ponders Obscured Layers of American Landscape

Curated in conjunction with September’s tenth annual Gila River Festival, held in Silver City, New Mexico, Michael Cook’s “The Notion of Landscape” is an invitation to ponder landscapes at a multitude of levels. While most events connected with this festival, whose subtitle is “Celebrating America’s First Wilderness River,” are designed to attract environmental activists and outdoor enthusiasts, Michael Cook’s exhibit offers the opportunity to step beyond the Gila and experience transformed American landscapes as a phenomenon not limited to a single place. Open for viewing through October 17, 2014 at Western New Mexico University’s Francis McCray Gallery of Contemporary Art, this solo exhibition offers activists and enthusiasts of all stripes a chance to reflect upon the constantly-evolving nature of the American landscape.

Every landscape is formed of many layers, and Cook has taken this concept of layering to great depths. In “Busy, Busy, Busy,” ancient desert hills and sky form the backdrop for a grid-scaped city filled with bright smudges of an endless Technicolor rainbow assaulting the senses. Below these city streets lies another network of thrusting lines, formed by fracking tunnels reaching deep into the earth. Intersecting nature’s curving conglomeration of solid rocks and oil pockets, these angular fracking faults mirror the distortions created in the surface landscape by the roads which carry the thirsty, fossil-fuel-guzzling machines that necessitate this deeper invasion. Buried further still is an ancient human skeleton, which might soon be reached by those fuel-seeking fractures, perhaps disturbing the very history — or definition — of what it has meant to be human. Overlaying — and in some sense dominating — the entire landscape is the opposite of this ancient skeleton: the ghostly outline of a modern man, clad in suit and spectacles, clutching a corded telephone handset.

In stark contrast with the obvious layering in “Busy, Busy, Busy,” the ephemeral “Instructions (Niagara)” seems to fade from view within the fog and mist generated by these iconic falls. The entire landscape is heavily obscured, with the notable exception of two dark — and yet spectral — figures, one of a human silhouette looking out over the river at the foot of the falls, and the other a boat with looming smokestack. Nearly impossible to grasp in a photograph of the painting, but crystal clear when viewed in person, is another ghostlike human overlay, this one of a swimmer with fogged goggles. Viewed with the lens of the Gila River in mind — which can be forded on foot for much of the year — this overflowing profusion of water seems to speak to the excesses of abundance which can obscure a paucity of spirit that lies deep and fundamental in the American psyche.

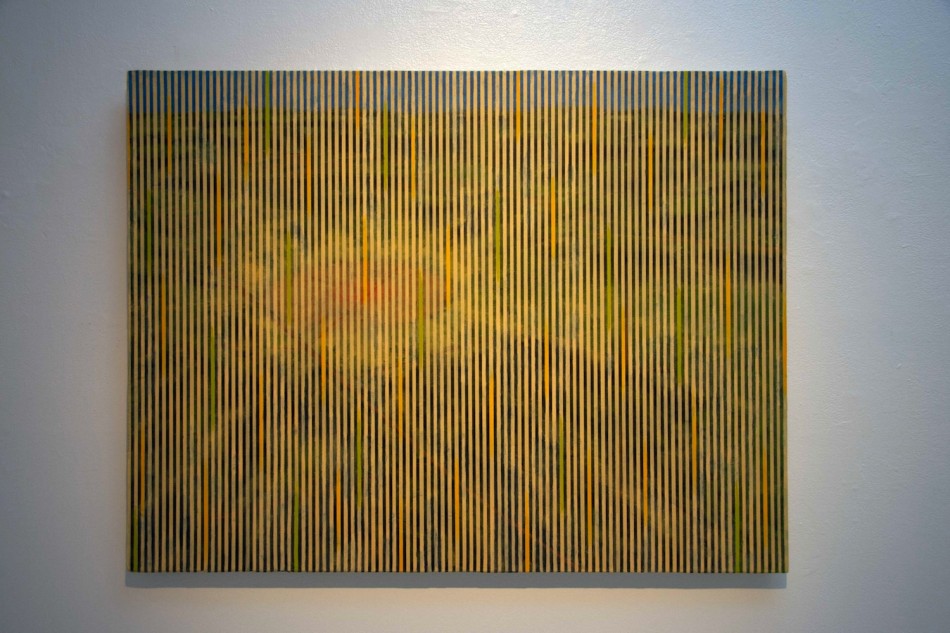

Obscuration is a theme in many of Cook’s notions of landscape, including three paintings from his Venetian series. Using vertical venetian blinds to partially mask and distort our view, these works create a distractive cloaking which makes discernment of the landscape layer difficult. “Venetian (Socorro)” looks out upon the Very Large Array, west of Socorro, N.M., an astronomical radio observatory consisting of 27 radio antennas that continually search the heavens for signs of intelligent life. The venetian blinds reflect purples and yellows not present in this landscape, perhaps mirroring visual interference caused by the viewer’s own agenda or baggage, or perhaps distracting elements present in the room in which the viewer stands.

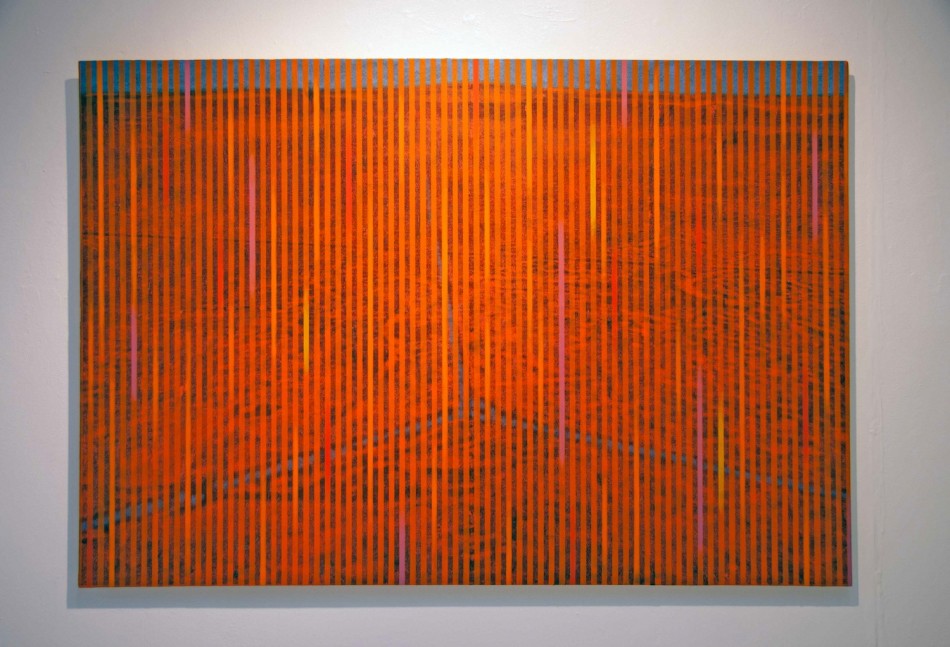

There is likely a connection here between the American agenda to seek intelligent life in space while ignoring the intelligence of the many beings inhabiting our landscapes here at home. Being unable to shed our own baggage and distracting elements creates a layer of interference — and perhaps obfuscation — in any scientist’s ability to interpret those incoming radio signals. “Venetian (Alamogordo)” points to another New Mexico site which holds scars of an even more destructive chapter in the U.S. manipulation of landscape: the Trinity Site outside Alamogordo where the first atomic bomb was detonated in 1945. Ironically, the reflective surfaces of those venetian blinds create a yellow-green pattern which appears to teem with life, rather than mirroring the toxicity of a mushroom cloud.

Another landscape which appears full of energy in this exhibition is “Instructions (Orton),” featuring an ethereal, elegant plantation house seen through a veil of insubstantial green trees. Smudges of gray could mimic the dim perspective of a twilit era, while fluorescent pink fireflies dot the scene with garish neon brightness (again, these are almost invisible in photographs of the work, but quite evident when viewed in person; does this in itself speak to the critical importance of encountering landscapes in person rather than secondhand?). Whether the icon of an unsupportable past, or of the dangers implicit in some mnemonic versions of the Old South, Cook clearly has no compunction about speaking to the limitations of landscapes viewed through an idealistic haze.

Cook is most explicit in regard to the limits of American vision with “Died of a Theory.” The title comes from a quote by Confederate President Jefferson Davis who believed that, if the Confederacy failed, it would be because the theory of states’ rights and nullification was untested and perhaps not viable. The painting is a collage of images set against a landscape covered in dirty smog or airborne gunpowder. A crow plummets to its death while a bull’s-eye on the opposite side of the painting might have been what the shooter was aiming at. A large capitol building glows a sinister and reflective red while also appearing to be centered in the gunner’s scope. While the war taking place might be against any number of foes on the American landscape, internal or external, there is no question that the battle has destroyed much of the value of the geography under contention.

While the Gila might be America’s first “designated” wilderness river, there is no question that there are many types of American wilderness that require exploration rather than exploitation. Michael Cook’s survey exhibition takes us on a profound journey through the myriad layers of mediated meaning within American landscapes, reminding the viewer that it is seldom possible to observe everything through a single lens.

Michael Cook, Busy, Busy, Busy

Michael Cook, Died of A Theory

Michael Cook, Instructions — Niagara

Michael Cook, Instructions — Orton

Michael Cook, installation view

Michael Cook, Venetian — Alamogordo

Michael Cook, Venetian — Socorro