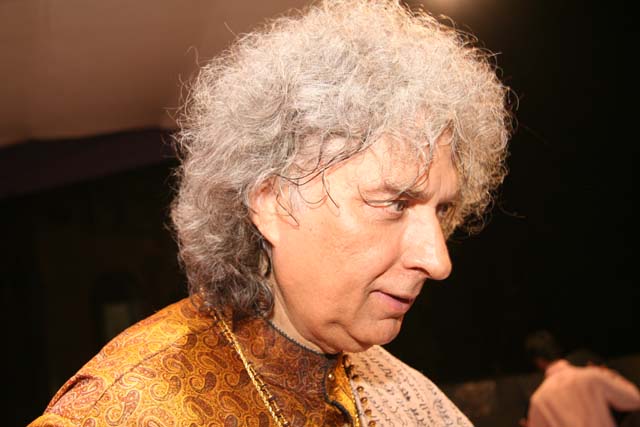

Shivkumar Sharma

Shivkumar Sharma and Zakir Hussain in Telepathic Rhythm

Years ago, I grabbed a ticket to my first classical Indian music concert and somewhere halfway through entered into transport. Legendary maestro of the lute-like Sarod, Ali Akbar Khan, sat cross-legged in loose white silk, fingerboard resting in his left hand, the strings and steel spangled with stage light. His fingers slid over the strings, notes rising and falling through a series of microtones with the erratic beauty of a kite. He could affect a tense shimmer, put the raga through fierce concussions. It was a religious, Vedic animism, unfolding as meditation and ecstatic play. All in startling synchronicity with the tabla’s prodigious inventions.

I’ve learned much since then; but when in thrall of Pandit Shivkumar Sharma and tabla legend Zakir Hussain, who performed on May 4 at Albuquerque Academy, I was assured that knowledge will go only so far. (Outpost Performance Space, organizers of the concert and sponsors of the New Mexico Jazz Festival, specializes in this kind of magic.)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sMr7Ki-ztuI

Shivkumar, now in his 70s and with the stature of a mantis, rested his dulcimer-like santoor in his lap, his hair billowing silver. Holding small, narrow mallets between his fingers, his elbows floating, he presided over his instrument as much as played it. Its 98 strings comprise an audible history of Persia, Asia, parts of Europe and the Mediterranean strung in miniature across a shallow, semi-rectangular box: the Egyptian lyre, the cymbalo of China, the mannered plink of a harpsichord. When played with only the fingers, it possesses the graciousness of the harp. Palmed, it becomes more a percussive drum of string. And seeming biographical, Shivkumar’s santoor can affect a perennial innocence, no matter how driven, virtuosic, capricious. Imagine small pebbles dropped by a child (John Cage?) onto piano wire.

Zakir Hussain has always been Krishna-esque: rhapsodic lover and musician, he plays with “speaking hands,” and they can be in their endless rhythmic phrasings like the epic advice given in poetic passages by Krishna to his warrior hero in the Bhagavad-Gita. While the sheer generative nature of his rhythmic imagination is unsurpassed, Zakir plays to the collaborative essence of Indian composition. It would seem he creates telepathically with Shivkumar, reading a musical score in the particular rhythmic fall of the mallets, the maestro’s nods and expression. His fingers rap sharply as on a hard hollowed door and the santoor answers; his hands gallop like a god in pursuit and Shivkumar matches him, note for note. That they also know through sadhana (ardent practice) how to do this goes without saying.

Invariably, there is a collective moment of awakening in classical Indian music. Out of the first movement’s slow, extemporaneous meditations on the raga, a pulse appears, and though worlds will come and go, this signal beat will never rest. Shivkumar, improvising an arrhythmic moodscape, wandered pentatonic drifts, lingered in irresolutions, caught flecks of clarion brightness. His hands shivered over some small corner of the box; the resonance frayed, returned incandescently. Then his mallets came down and then down again, establishing time, the sure beating heart. It is among musicians a technology of transport – and for us a hint of the cosmological rather then cosmopolitan ear. Nadha Brahma, the sound of God.

There is genuine grandeur in the theoretical complexities of the classical Indian tradition, extraordinary nuance in the stated formal principles of the emotions. For those of us bewitched in the audience, the mind , unable to keep up, surrendered with a smile; the ego undone. After such a concert, people can sound as though they’d been witness to some numinous event of nature, a sudden lift of snow geese off a lake, the first sliver of a lunar eclipse.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nNjRoEkv_WE