Walter de Maria "The Lightning Field", (1977)

The West Is Out There

A long wait at the DMV, while my 17-year-old son took his driving test, was interrupted by a tweet on my Blackberry. It was Tyler Green sending a link to Blake Gopniks recent Washington Post article about Gopniks visit to Lightning Field (above). Gopnik wrote that the setting of Lightning Field, near Quemado, New Mexico, is “a classic patch of sagebrush-covered land, set on an empty plateau 7,200 feet high. A ring of jagged mountains (is) at its edges, out-cliché-ing any Hollywood western.” The remote site for Walter de Maria’s grid of steel spikes, Quemado, and Lightning Field, are edged by the Malpais, a jagged black volcanic landscape over which Spanish colonists really rode their horses (gingerly) into New Mexico. Green tweeted: “If you think Lightning Field’s setting is a cliché, then isn’t, uh, the entire American west a cliché?”

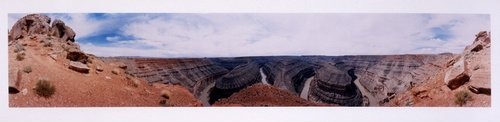

Gus Foster “Goosenecks of the San Juans”, Edition of 10 Panoramic color print 17 x 88 in

Yes. Just like a picture in Lonesome Dove of cowboys galloping across every Western landscape, segments of the American west are overused and predictable. There is a cliché perpetuated in certain art objects, films, and books, that continues to assign to Western pictures traits of independence and adventure. In pictures, these are instilled in examples as various as 19th-century landscapes by Albert Bierstadt or late 20th century Untitled Film Stills by Cindy Sherman. Without Richard Prince’s Marlboro men frontloading the amber red of the dust tracked up by cattlehooves into the art rooms, maybe only advertising would have the task of depicting the West to seekers. After all, those seekers still find the West – image, cliché, and all – a place to be alone, where open spaces don’t block your vision.

As any visitor to many safely antiseptic public sculptures of heroes on horseback can attest, the motifs of much Western art deal in heroes, fights, rustles, rumbles, greed, cruelty, enterprise. And: victory, or defeat. If these are values of Manifest Destiny and the westward-spread of the new nation, they may also be easy to like in painted pictures – especially if you never cared, say, for the anti-objecthood of the art of De Maria and his brethren.

Cindy Sherman “Untitled Film Still #43”. 1979. Collection The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

To think of the movie scenes-clichés that gave us our national view, think of John Wayne, in John Fords movie The Searchers, tracking the Apache chief Cicatrix to get Natalie Wood back. Or the fact that New Mexico as a setting for films today represents everything from itself to California to the Middle East. (Or: that its Kenya in tourism brochures touting New Mexico as an eco-tourism destination now.)

What then might be the significance of the dwindling vitality of the Western painting market, judging by auction results at July’s Coeur dAlene? Several Charles Russell paintings, as well as Frederic Remingtons and N.C. Wyeths, went unsold this year at that Idaho auction that is the market-maker of Western-archetype-as-art-market. The 2009 auction produced only $11.66 million in sales, down strikingly from 2008s $37 million and the previous years banner $35 million. What have been boom years have given rise also to popular living Chinese painters of the Western landscape: Top selling living artists at Coeur dAlene were Mian Situ and Z.S. Liang. Charles Russells “The Truce” (est. $2-$3 million) a watercolor and gouache on paper, sold below estimate for $1.8 million, presaging perhaps that record sums on range paintings might be, like the range wars, just a memory.

Into this world of strange-bedfellows (Chinese-painted Western art and Walter de Maria), comes photographer Gus Foster – represented by Gerald Peters Gallery – who might be a mythmaker all his own. Foster’s photographs communicate in a way that is still representational, but closer to the vision quests of artists for whom the West is as much a frontier of critical engagement as a vista of spectator sport. Foster is a Yale-educated art historian who spent ten years (1963-1972) as the curator of prints and drawings at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. He then moved to Los Angeles and a few years later settled in Taos, to pursue his panoramic photography career (Goosenecks of the San Juans, below). Hes an avid hiker who has scaled many peaks throughout the Rocky Mountain West hauling hundreds of pounds of camera gear to capture 360-degree views.

Gus Foster “Goosenecks of the San Juans”

Dealer Gerald Peters has told Ellen Berkovitch he thinks of Foster as a nature mystic. Foster named his Alpine-La Mancha goat William Henry after well-known photographer William Henry Jackson, an early photographer of the American West and a member of the first Hayden survey of the Rocky Mountains. Sipping on the vodka rumor? Tack up Fosters belt a notch on the cinch studded quirky freedoms of the West.

Ellen Landis curator of art at the Albuquerque Museum hails Foster as prescient : “His vision rivals the grandeur of the landscape itself, drawing the viewer into a space that is vast and powerful.”

Yet Foster admits that panoramic photography “can only begin to suggest the spectacular reality of the mountain peak experience.”

There are and have been days for me growing up in the West; living in Southwestern Colorado where I’ve interviewed many artists about landscape as subject; traveling across the West; stopping near the top of Wolf Creek Pass or watching a thunderstorm roll in across the Taos Gorge; that I have been a silent observer to nature. There is a part of me that wants to capture that moment on film, or canvas, but I’m always stopped because the moment changes instantaneously. It is never the same, fleeting, and no matter how panoramic, there is still something absent from view, that that the body senses and the eyes filter into the nervous system. The argument against mediation and for experience.

For critic Blake Gopnik, Lightning Field is about framing the landscape, so that you understand it better and differently – but recall that for Gopnik, looking around, the setting immediately transcribed in his mind as Western “cliché.” I think De Maria would disagree and say Lightning Field is about being in, not just in front of, the art, a work so large it cannot be viewed except by walking it. Around and through. And through. Just like the West. A passing-through doesn’t come close to a knowing.

Other shows of Western art of note around the land(scape) include the Corcoran Gallery of Arts look into the relationship of nature to national identity, headlined by the Frederic Erwin Churchs 1857 Niagara. And the Denver Art Museum has a Charles Russell show of paintings from the Petrie collection, through Aug. 30.