Jay De Feo Show, by Artist of “The Rose”

Artist Jay De Feo was for the duration of her life associated with the Bay Area, and sometimes mistaken, by her name, for a man (some speculate that being named Jay helped her win the 1951 UC Berkeley fellowship that took her, after graduation, to Europe and North Africa for a year and a half, Florence for six months of that). However, her work is that of a brilliant changeling female.

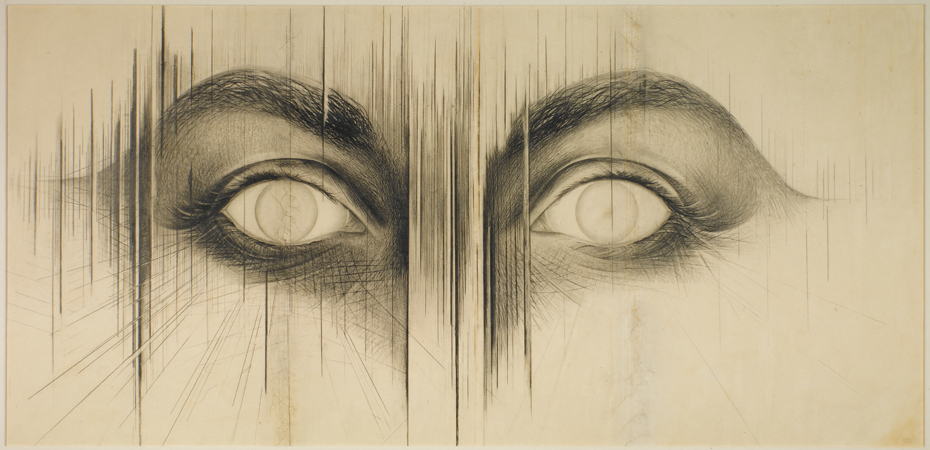

A painter, draftsman, photographer and sculptor – a multimedia maven before anyone had uttered the word postmodern – De Feo was a meticulous formalist and a gesturalist who tapped emotional profundity. She was diagnosed with lung cancer in 1988 and died in 1989, age 60. At the time she died, her masterwork, the painting named The Rose, had been under assault by neglect, hanging entombed behind a wall at San Francisco Art Institute, later bolted to a conference room wall. Its surface was practically sagging off the white magnetic front, a surface so energetic and ancient it might have been a stelae.

Jay DeFeo working on an early version of "The Rose", originally titled "The Death Rose"

When I wrote a story about Jay De Feo for Art & Auction magazine, published March 2007, Whitney Museum of Art associate curator Dana Miller — who has a DeFeo retrospective in the future of the Whitney, date as yet unannounced — told me that the only 20th century artists to whom to potentially compare De Feo would be sculptors Lee Bontecou and Eva Hesse — “and they arent really close at all,” said Miller.

Now, for the second solo show of De Feos work to be mounted by Dwight Hackett Projects in Santa Fe, in collaboration with the estate of Jay De Feo, “Samurai” series paintings and collages on paper are on view. They are singular. De Feos self-choreography was an elaborate tango between form and gesture that kept her, and keeps viewers, acutely alert for where in a picture plane she is going to do the unexpected. Sometimes in this show it is the addition of a straight pin, its tiny black or blue metal nubbin, this side of shiny, slipping through a collage element to affix it to its surface. The colors are De Feos palette of gray, black, white, often worked so that you see the signs of scraping, addition, subtraction, accretion, that she coaxed into magnificence. The show is on view through September 12th. Co-trustees Leah Levy and C. Ursula Cipa administer the Jay De Feo Estate that has collaborated with Hackett to bring, now, the second deep look at this artists life and rigorous art to Santa Fe.

De Feos1959 gallery show at Dilexi Gallery, San Francisco, introduced her to collector J. Patrick Lannan (Sr.), who offered outright to buy Deathrose, The White Roses (later The Roses) first incarnation in paint. (She did not sell, but soon after that remounted The Rose onto larger stretchers, and in to worked on the painting for eight years.) When she had to vacate her studio in 1965, her pal Bruce Conner made a movie about the paintings removal from Fillmore Street. De Feo is a forlorn figure, sitting alone on the fire escape smoking and watching the white-suited movers contend with her colossus. A 10-foot canvas supporting a literal ton of white and gray oil paint, De Feo had grooved this mass of material into an architectonic abstraction of 18 radiating lines; she considered The Rose the “central core” of her lifes work. (“The White Rose is a fact painted somewhere on a slow curve between destinations. This is all I remember. This is all I know,” she wrote in 1965.) The paintings physical restoration was really a Lazarus tale that began in 1992, nearly 30 years after its wanderings started, and three years after De Feo died. It has been shown at the Whitney repeatedly since the 1995-completed restoration, first in 96, 99-00 and 03-4.

“The Rose is the female version of Jackson Pollock,” Miller told me.

The Whitney at the time of our interview held the largest public collection of DeFeos work-15 DeFeos and nine nude portraits of her by Wallace Berman- and at that time estimated the full retrospective they are planning will occur in 2011-12.

This, said Miller, will be an opportunity to show that “DeFeo was not an artist who just disappeared.” Called superbly “an impressionist of cosmic space,” De Feo indeed looks intensely spatial and modern today. The first Hackett show was held August 5- September 23, 2006, and focused in part on the artists turn in the 1970s to using photography as her vehicle to record plant life. The artist, after the Rose, had had a breakdown. It was photography that helped unlock her stasis and become prolific again in the 1970s. She used photography to revisit themes of drawings and paintings on paper including the 1956 painting she had shredded, White Spica, which she revisited in a great series of photographs in 1973.

DeFeo worked serially and experimentally, making perhaps hundreds of studies in drawing and photo-hybrids of such domestic objects as her vacuum cleaner, shoe trees and drawing erasers. The eraser form, a black triangular shape, recurs visibly in this “Samurai” show – of which all the works date from 1987. And its appearance as a collage element is both humorous and winning.

Although De Feos name thrives quietly – known by connoisseurs, curators, and collectors as synonymous with the eternal bloom of vision — an uptick in critical interest occurred in the earlier part of this decade, as more of her work was collected by the Whitney, the Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco MOMA, The Art Institute of Chicago, The Norton Simon Museum , University Art Museum in Berkeley, Mills College Museum of Art , The Weatherspoon in NC and The Logan in Utah. But gallery shows are comparably sporadic, which makes this one such a treat. LACMA owns and shows the 1958 painting the Jewel. WACK! a feminist art show that Connie Butler curated in 07, and which traveled into 08, featured perhaps a dozen of De Feos 1970s “tripod” works — a paean to how photography had been the mechanism of getting her back to work, after the exhaustion of The Rose.

The Pompidou Center hung an exhibit last May to September 2008, “Traces du Sacree,” Traces of the Sacred in Twentieth-Century Art, which revisited DeFeo (and others) in a show of 350 works. From curatorial notes, “The exhibition investigates the way in which art continues to demonstrate, often in unexpected forms, a vision that goes beyond the ordinariness of things and how, in a completely secular world, it remains the secular outlet for an irrepressible need for spirituality.”

Both that De Feo goes so far out beyond the ordinariness of things, and delivers a spiritual punch, is more than underscored in this show of Samurai. Beautifully hung, a pleasure to encounter, signs of a cosmic spatialist undeterred by a marriage of gesture and form.

Many thanks to this site, The Edge of the American West, for linking to the White Rose movie, proof that just about everything in the world (save the art itself) is online. If you can see this show at Dwight Hackett Projects, dont miss it.