Robert Adams Photography at DAM: A Bodhisattva Sees the West

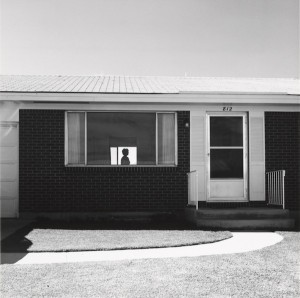

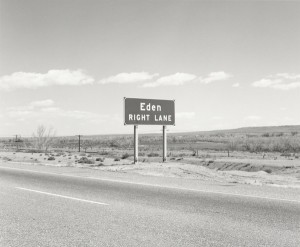

Photographer Robert Adams is a bodhisattva to the American West: “I want to make accurate photographs of the western landscape. One goal is to show what’s gone wrong so we’ll change it. Another is to show what’s right so we’ll take some hope in it,” he wrote.

Through Adams’s viewfinder, the West, the ideal and the desecrated, clarifies.

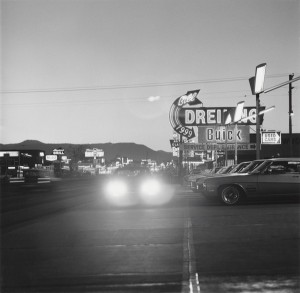

When he began photographing in the 1960s and 70s, landscape photography was hooked on the utopian ideals of Ansel Adams. The majestic National Parks. Yet Adams opened his aperture first to the starkness of Colorado’s high plains, wheat fields and sky. Then he pointed his lens on the suburban sprawl of Colorado, the changes to pristine California’s landscape, the clear-cut forests of Oregon. He followed rivers, found beautiful views in dangerous places like a hogback on the outskirts of suburban Denver, majestic peaks in the distance. He composed an open, airy photograph where the viewer is rooted in the road standing, looking out at the expanse.

The title of the photograph is “South of the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant, Jefferson County Colorado” and was taken while Rocky Flats was still manufacturing nuclear weapons. The photo is taken downwind from the plant and the dichotomy and irony of the image and the location are elemental to the work of Robert Adams. There is always much more than meets the eye.

“The pictures record what we purchased, what we paid and what we could not buy,” Adams wrote. “They document a separation from ourselves, and in turn from the natural world that we professed to love.”

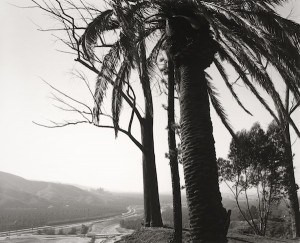

Colorado was Adams first exposure to the natural world. He moved with his family to Denver from Madison, WI in 1952. He was 15 years old. He moved to California for college, earning a doctorate degree in English from USC, and when he returned to Colorado in 1962 as an assistant professor of English at Colorado College, he noticed how much the area had changed. He began photographing Colorado Springs and Denver at this time in order to document the disturbing and rapid transformation of the landscape with tract houses, highways, strip malls and gas stations. He told curator Eric Paddock that it wasn’t growth, but diminishment. A few years later he spent time back in California and documented the changes again. Then, after winning a MacArthur Fellowship, he and his wife relocated to Oregon, where he has lived since 1997. It was there that his most prominent work, and that featured in the documentary series Art:21 was created—the images of the clear cut forest.

All of these works and more are featured in this retrospective, now at Denver Art Museum. The exhibit, organized by the Yale University Art Gallery, features 244 photographs spanning 45 years and includes a three-volume hard cover catalog featuring more than 400 works from the artists personal archive.

Unique to the Denver exhibit are the series of 24 photographs of a single Cottonwood tree near Longmont, Colorado showcased on a creamy yellow wall at the entrance to the exhibit, which speak to attachment, love, loss and change. Essentially a formal study of the tree in differing seasons and light, the series concludes with the stump of that tree, left behind after a bulldozer has cleared the grassland. Also, five rich, tonal images of the Pacific on pale blue walls. These are of the estuary where the Columbia River enters the Pacific carrying dioxins from paper mills and radionuclides from the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. They are serene images, which must be read for their criticism of our neglect of the environment.

Additional galleries painted a soft sage green make the oversized Gallagher Family Gallery on the main level of the Hamilton Building more homey and accessible for the relatively small photographs that make up this exhibit. One see’s in Adams photos the poignancy and lucidity of Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange and equally the epic hopefulness of William Henry Jackson.

There’s a tension to the beauty in Adams photographs. And at the end of the show one could conclude that perhaps he has found the simple pleasure in looking, the restful ease of what surrounds him. He and his work stay, guideposts into “a landscape into which all fragments, no matter how imperfect, fit perfectly.”

Robert Adams

The Place We Live

Denver Art Museum

Gallagher Family Gallery

Through January 1, 2012

www.denverartmuseum.org