Retired French electrician Pierre Le Guennec

Picasso and the Grand Theft Electrician

NEW YORK- 271 works by Pablo Picasso (including more than 200 drawings) are now in the hands of a French cultural police force called the National Office against Traffic in Cultural Goods (office central de lutte contre le trafic des biens culturels). The pictures havent been seen since at least the 1970s. The Picasso family now believes they were stolen at that time by an electrician, Pierre Le Guennec, who worked in several of Picassos residences. From all indications, the works were never missed.

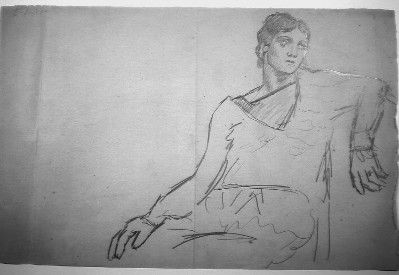

A photo of one of the supposed stolen works: a drawing titled Olga Accoudee (Olga elbowed) by Picasso

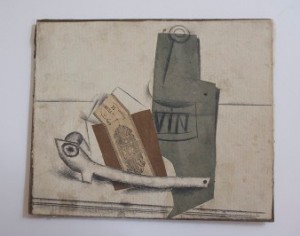

The works date from 1900 to 1932, ranging from pictures of Picassos friends in early impoverished “Blue Period” Paris days to some finished drawings in the precise highly valued style of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres from the 1920s. There are also Cubist pictures in the mix, which tend to bring high prices at auction. Drawings from around 1920 of Picassos ballerina wife, Olga, are also part of the cache.

Papier colle pipe et bouteille (Copy paste pipe and bottle) by Picasso

In September, photos of the works were sent to the artists son, Claude Picasso, by Pierre Le Guennec, now 71, who asked the Picasso family to certify the pictures as authentic, presumably in the hope that such a certificate would help them sell. In September, Le Guennec arrived with his wife and a suitcase containing the pictures for the Picasso heirs to examine. Le Guennec was an electrician who worked in La Californie (Picassos house/studio after the war) and in two other of Picassos houses.

Le Guennec says the pictures were a gift from Picasso. (Picasso did give away art, but he always inscribed pictures that he gave as gifts, and these are not inscribed. Nor was Le Guennec ever known to be a friend of the family, although he did install alarms in several of Picassos houses.) When police seized the pictures at Le Guennecs house on October 5, they arrested the former electrician, but released him after 48 hours. Hes now free, although not talking to the press, and a court will determine who owns the pictures. The statute of limitations on theft of the works is three years, yet he could be prosecuted on other charges. “What will happen, will happen,” he said to Vincent Noce, the reporter for Liberation who investigated the story.

a painting of a hand by Picasso

The Liberation article reports that the pictures were in groups that Picasso left with his dealer, Paul Rosenberg, before the war, and were sent to Picassos home in the south of France when French laws intended to provide housing after the war ruled that a citizen could have only one residence. It is not clear why these pictures were not looted by the Nazis, since Rosenberg was Jewish, and much of his property was seized.

The information on which Liberation based its story (which I received from Vincent Noce before its publication) came from Claude Picasso, the artists illegitimate son who plays a crucial role among the Picasso heirs, and from police who investigated Le Guennec. I spoke to the Picasso biographer John Richardson, who confirmed that Le Guennec was not a friend of the artist or the family. Richardson says that the 271 pictures would have enormous value – between $50 and $100 million, perhaps more.

Insiders say that Le Guennec may have approached the Picasso family in the hope of a settlement or payoff, which they suggest is unlikely from family members who would hesitate to pay off someone whom they consider to be a thief. A court battle could follow, which means that the value of the pictures could increase by the time ownership is determined.

(Picasso photos provided by the Succession Picasso. Credit: Succession Picasso.)

(top photo: Claim to second trove of Picassos: Retired French electrician Pierre Le Guennec (AFP: Valery Hache)