FIFA in Montreal: Framing Design in Films on Art

Why arent more films about design made or shown in the US? Ill let readers, designers and filmmakers debate that one.

In the meantime, consider films on design made in other countries that were at the International Festival of Films on Art in Montreal (FIFA, March 18-28, 2010; www.artfifa.com), and eat your heart out.

Among the 230 films at that annual event, lets begin with something as simple as German Design, which is the subject of a three-part documentary of htat title by Maren Niemayer. Its a dutiful introduction, ranging from the Bauhaus to the present, examining how designers balance living in an existing tradition and discovering something new, and then selling it to consumers.

Design mavens, eat your heart out. The Rietveld chair.

The focus here is moving German design beyond Germany. We observe German designers training in Milan and returning to home to refine German products for firms like Braun and Siemens. We see German fashion (who knew?) winning over customers in Japan, where a store called Wut (Rage in German) sells Berlin chic in Tokyo in a space that looks like a ruined underground bathroom. In the films final section, on communications, an edgy branding firm brings “timelessness” to Dornbracht, the bathroom fixtures company, with an advertising campaign that featured a nude model, shot from above, in one of the firms bathtubs. The campaign worked.

Theres an annoying English-language narration in German Design, and the film avoids automotive design, which is the countrys most important export. But the documentary from Deutsche Welle TV stands above anything on design that youll see on American television.

The gold standard for films on design is the ongoing Centre Pompidou series, produced with ARTE, the French-German cultural television partnership. Two of these 26-minute films were at FIFA, each directed by Danielle Schirman.

The Rietveld Chair (La Chaise Rietveld) (above) looks at the chair, built in the Netherlands by Gerrit Rietveld in 1918 and painted in primary colors in 1923, which seemed more like an architectural model than a piece of furniture. Schirman reminds us that the chair was also a link between design and art. Rietvelds colors prefigure the simplified palette of Piet Mondrian.

Schirman combines animation, archival footage, and connoisseurship as she looks at Dutch design, and as she analyzes one of the great achievements of French post-war mass production, the Compas Table (designed in 1948, manufactured in 1952, and used in every French hospital and university). French designer Jean Prouve showed how stainless steel furniture produced with industrial machinery could be elegant. In The Compas Table, Schirman makes us remember how revolutionary Prouve was in supporting weight on the most minimal frame.

So far, the Centre Pompidou series is only in French, so youre not likely to see this ingenious approach to filmmaking on American television. It should be shown in every design school.

Tadao Ando's Koshino House. Japan (1981)

On architecture, Tadao Ando, Koshino House (above), offered a case study in the work of one of the living masters. Ando designed this concrete house on a large wooded site in Ashiya Japan for Hiroko Koshino and her family. Rax Rinnekangas of Finland, a veteran director of architectural documentaries, approaches the understated project (1979-84) as a rejection of western encroachment into the Asian world, even though the siting of the reinforced concrete house in a grove of trees is also a study in the influence on Ando of Le Corbusier and Kevin Roche (a major force at the time). Kinnegangas gives his film a zen-like pace that fits the sepulchral house and the personality of the man who designed it.

In contrast, The New Rijksmuseum, made for Dutch television by Oeke Hoogendijk, takes you to a tower of Babel. The museum, which closed for renovations in 2003, was to have reopened in 2009. The documentary takes you through the protests, design revisions, and administrative bungling which will keep construction going until at least 2013. Its a comedy of errors that informs you how institutional architecture really happens. Bear in mind that the Central Station and subway projects underway in Amsterdam now make this project look efficient.

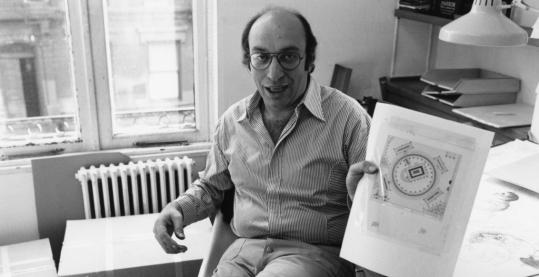

In a North American perspective on design, Inform and Delight; The Work of Milton Glaser, the debut film by Wendy Keys, Glaser takes us through productive half-century career which informed much of what we know of graphic design in New York.

A founder in 1954 of the design team Push Pin Studios, the Bronx-born Glaser, now 80, teamed with Clay Felker in 1968 to co-found New York magazine, the weekly which combined New Journalism with design that it applied to the coverage of everything from Richard Nixon to cheap restaurants. (Who would go to New York Magazine to look for creativity these days?) In the 1970s Dog Days of New Yorks financial crisis, Glazer designed the I Love NY logo, which has been ripped off to express the love of everything from New Jersey to Islam. (I own an I Love Islam keychain.) Glaser admits that he did the design pro bono, and never made a cent from its infinite iterations.