Edward Ranney’s New World Landscapes: Shaping Culture

Edward Ranney is a visual artist who has learned as much as he possibly can about ancient cultures and how they survive and continue to exist in contemporary society. According to Eric Paddock, curator of photography at the Denver Art Museum. Ranney who has been photographing for almost 50 years, creates images that hide or disguise the artists viewpoint. “They are clean, sharp images distantly related to minimalism and Western topographic photographs,” Paddock said. Think Hiroshi Sugimoto meets Ansel Adams. An exhibit of 30 images from Ranneys oeuvre is currently on display at the Denver Art Museum on the 4th floor of the Gio Ponti Building in the Pre-Columbian and Spanish Colonial Art galleries in an exhibit titled “Shaped by Culture.” Paddock intentionally decided to exhibit the work not in a stark photography gallery, but instead amidst the ancient artifacts of the Americas because “the photos lend geographical and physical context to the artwork,” he said.

Edward Ranney, "Bath of the Nusta," Ollantaytambo, Peru, 1975. © Edward Ranney, courtesy of the artist.

The Denver Art Museum holds the finest collection of Spanish Colonial painting and furniture in the United States. The Frederick and Jan Mayer Center represents nearly every major culture in Mesoamerica, Central America, and South America, with particular strength in arts of Central America and Peruvian, Ecuadorian, and Mayan ceramics. The collection is unparalleled and comprised of over 5,500 objects exhibited in unified presentations and open storage and the Mayers also support fellowships and scholarships to promote advanced research. When Denver decided to host the Biennial of the Americas, including DAM and the Mayer Collection was already a foregone assumption. From large stone sculpture to fine gold and jade objects the galleries are a perfect place to get lost in the ancient past all the while realizing how very similar we humans remain thousands of years later with our love for beautiful objects in gold, jade and silver perpetual.

Necklace, Maya, AD 250-800, Copan, Honduras. Shell Beads. Denver Art Museum; gift of M. Larry and Nancy B. Ottis

The bulk of Ranneys photos are found in a large conference room filled with tables and chairs. There is not much wall space open in the Galleries. A few photos are placed near doorways or passageways to other galleries. All are hung on the walls. I had hoped to find the works propped on easels to emphasize the “art” aspect of each work (though they would have taken more floor space and been far more susceptible to damage from visitors). Ranneys photos, while exquisite, are not large. The prints shown are no larger than 22″ x 28″ and most are 11″x 17″ or as small as 6″ x 9″ and significant bilingual wall text accompanies each photo. Many of the works get lost in the setting, the black and white images fading into the background, and while the museum was filled with visitors on the Saturday I visited, the few who had found their way from King Tut to the 4th Floor paid any attention to Ranneys photos. A shame because each photo is a quiet meditation on a temple, a forgotten past, or the beauty found in perfectly fitted stonework. I learned from two 1970 Gelatin silver prints “Carved Figures, North Court, Palace Complex, Palenque, Mexico” (above left) and “Stela A, Copán, Honduras” that Mayan artists had distinctive local styles. “Palenques sculptors excelled at individualized portraits in shallow relief. Copáns rulers, carved on vertical monuments called stelae, have idealized faces and meticulously rendered costumes and regalia,” read the wall text. Something I could then see in the actual Palenque and Copán sculptures on display.

I hope more visitors will take the time to visit the 4th floor galleries and see Ranneys images. The photographs speak about what it is like to BE in a place and DWELL in place and make an emotional connection to the ancient past. They provide the viewer with a glimpse into the enchantment of the past as it protrudes into the present. Paddock said of Ranneys photographs that they share “a profound silence, ease, and spaciousness that suggest his reverence and respect for those places.”

More than simply an exhibition of some photographs, this is a show about what it means to be human and the history of civilization. Its just too bad that the structure of the exhibit couldnt be less formal and more magical. The context within the Pre-Columbian galleries is not enough, but then again, how can one truly contemplate an artifact in a sterile museum setting and begin to fully comprehend the expansive and culturally rich peoples of the Americas, ancient or contemporary.

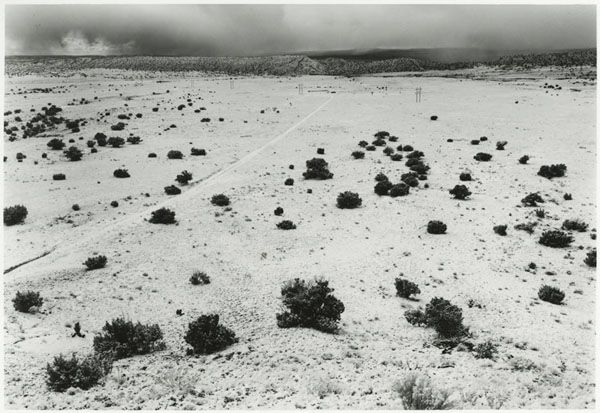

(top photo: Edward Ranney (1942 – ) La Bajada Drainage, Near Waldo, 1979. Silver Gelatin Print. Courtesy of the Artist.)