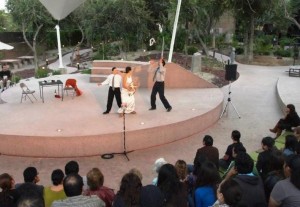

Antigona en la Frontera, performed outdoors at an actual border wall

Antigona en la Frontera: A Missed Opportunity at Revolutions Theater Festival

In Sophocles’ tragedy Antigone, the figure of Antigone confronts the unburied body of her brother Polyneices.

Creon, king of Thebes, has consigned him to lie un-shrouded on the battlefield where he fell, prey for vultures and carrion.

Pitiless human nature and predatory politics cast a residual image from the drama of 441 B.C.E.

Antigone, whether fighting in the antique setting of the civil wars of Thebes or the modern one of border wars in North America, remains a figure whose theatrical power adapts across centuries, armies and exiles. Syrian refugee women in Beirut have interpreted her plight. In Albuquerque, a Mexican theater troupe’s contemporary play of the tragedy, titled Antigona en la Frontera (Antigone at the Border), marked a first Friday of Revolutions International Theater Festival performances. (Featured image: Antigona en la Frontera being performed at a border fence.)

The group — Mujeres en Ritual Danza-Teatro y Teatro Laboratoria Tijuana — has performed Antigona en la Frontera as street theater on beaches and public parks in San Diego and Tijuana. But in the Revolutions festival context they took the drama to the National Hispanic Cultural Center stage.

The largely English-speaking audience had gone unwarned that the play would be in Spanish, without subtitles or supertitles, until immediately before the show began. The lack of comprehension aids was worsened by the fact of what easily could have been remedied by the festival organizers’ being more committed to a basic audience expectation that they understand the language of the play.

Of the three players onstage (four, counting a musician/flutist), only Antigona appeared in the action to remain consistently herself, a character described rather elliptically as being “from the past” and encountering two other figures “from the present.” This review cannot even accurately report which actor played which part as the program for the festival did not include this key information — or in fact, any biographical information even about the company.

What could be deduced was that Antigone hanged herself (with a noose) at the front of the play, a readable action which may have been a metaphor consigning the further actions to a realm of underworld or nightmarish imaginings.

Yet it was impossible to know if these imaginings pertained to Mexico, to war in general, or to a third element of being left hanging between worlds of dead and living, given that as a viewer you had to sit, effectively making your own reading up.

Unlike in a street context where audience members can come and go, or have options to interact with players that did not apply in this setting, the viewer experience was rendered opaque in the extreme. The 10-minute “talk back” after the show engaged the translating services of an earnest Albuquerque high-school student, who had seen the play the prior morning. He factually translated what actors and director Dora Arreola said, but one was left to wonder why a member of Albuquerque’s theater community could not have been tapped as a translator before the play began, or at 15-minute intervals during, alongside this troupe that must regularly improvise in street performance circumstances.

Let’s be really clear here that theater, music, opera, dance are performed in many languages and of course, that many forms exist without spoken words of any kind. But this was not true of this piece of theater. The actors interacted and spoke a great deal of dialogue. Antigona’s monologue when she uttered the name of the invisible Polyneices rang with a chorus of “hermanos and hermanas,” brothers and sisters. But the rest remained hanging out in the dark, and so did whatever else she had to say to us and the other brothers and sisters who could heed a political urgency only if they could hear it.

This missed opportunity seems inexcusably amateurish for this festival in its 15th year.