AIR 2, Will Wilson

Will Wilson’s Year-Long Survey Opens at Wheelwright Museum

This compelling survey of the last 10 years of Diné photographer Will Wilson’s practice is replete with visual correspondences and material implications. The visitor to the Wheelwright Museum’s gallery is encircled by a group of LED-lightframed, photo-collaged landscapes and interiors. Wet-plate collodion portrait prints hang from clips along the the inner gallery’s outer walls, next to a glass-beaded blanket collaboratively fashioned and encoded with QR code (eyeDazzler, 2012). Within that inner gallery, a portrait studio is recreated with Wilson’s antique standing camera and chair. Despite its being a small show, the imagery and objects informed by photography and technology are writ large.

Containing the show’s most arresting images is the light-framed Auto Immune Response series (see AIR 5, 2005). Wilson wears his emblem, the gas mask, in multiple photographs; it is also placed in the “portrait studio” and suffuses the entire show with ambivalence and foreboding.

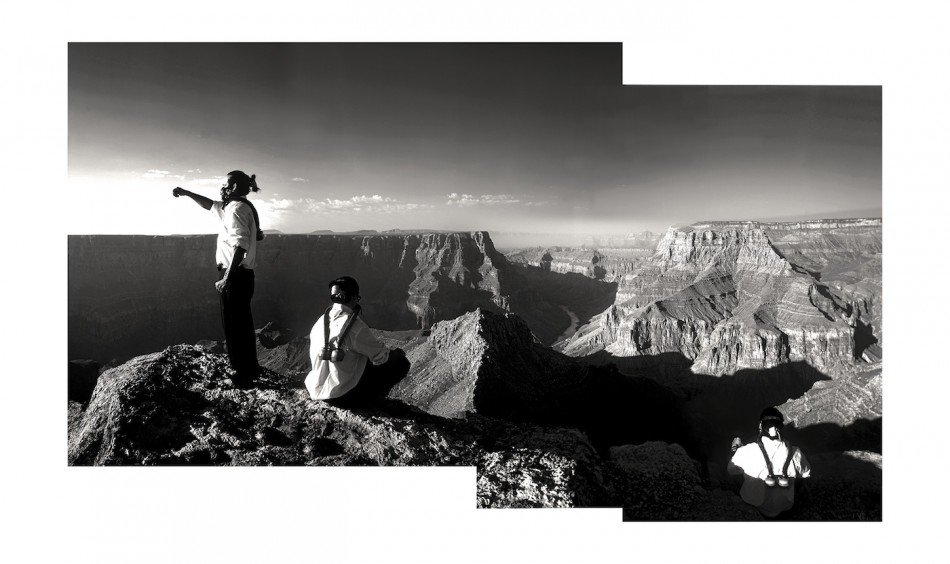

Across objects and processes, Wilson deftly challenges modes of cultural transmission. Received manners of landscape and portrait photography are cited and recovered for an art practice responsive to their contexts and assumptions. In the Auto Immune Response series, Wilson revises the intentional exclusion of Native Americans from traditional photographic images of the West by including his own gas-masked figure, multiplied by exposures, in apparitional postures of longing, bewilderment and reverence. Auto Immune Response 2 (2005) could be a traditional image of the Grand Canyon, except for the photographer’s triple across the foreground. On the left he stands with an arm outstretched, making an offering of corn pollen; at center and again on the right, he sits with his back to the camera — like us, absorbed in the spectacle. Yet his uncanny masked presence registers an ominous dread in the familiar.

In the Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX) series, Wilson has appropriated one historically prominent motif of photographic transmission. In the first decades of the 20th-century, Edward S. Curtis used the collodion wet-plate process to document what were considered the “vanishing” Native populations of the west. These iconic images, imbued with nostalgia and the applied romantic primitivism of an outsider with an agenda, helped to express a conception of Native Americans as “doomed to extinction” As Wilson appropriates and qualifies the antique photographic process, he acts as a “trans-customary practitioner” whose photographic subjects are often his indigenous collaborators. He asks each sitter to hold an object of personal significance. (His must be the gas mask, for it lies across the back of the chair in the inner gallery.) He alters the process by returning the tintype plate of the image to the sitter, out of respect for Native norms of personal representation; on the outer wall of the inner gallery at the Wheelwright, scanned prints from the CIPX series hang from clips, their tintypes pointedly absent. Yet this absence ironically disconfirms the implied thesis of Curtis-era photography: that the Native American is vanishing. The inkjet proxy materially alludes to the persistence of an unromanticized indigenous form of life.

Also worth mentioning is Auto Immune Response: On the consideration of invasive species, downriver from Los Alamos, NM (2014), a gorgeous LED-illuminated triptych of digitally enhanced, wet-plate images. Somber compared to its brighter, more open neighbors, this scene of masked solitude at river’s edge, enclosed by the blackened, rounded field, still delivers a heightened anachronistic shock. One fascinating glass-beaded blanket of the eyeDazzler series (woven by Wilson, Pamela Brown, Joy Farley, Dylan McLaughlin, and Jamie Smith) hangs on the wall of the portrait gallery. Atop the chair, under Wilson’s gas mask, is a traditional woolen blanket, woven by his grandmother; its pattern was the model for eyeDazzler.

The sudden proximity within this sculptural tableau between the family heirloom and its collaboratively executed relation conveys another reflective, enigmatic charge.

This show will remain up for a long time, until April of next year. Wilson’s work looks terrific in the Wheelwright’s hogan-styled octagonal gallery; it seized my attention despite the distracting and noisy renovation process under way elsewhere at the museum. I wish there had been wall labels for many individual works, or at least a diagram at the desk. Still, this compact survey suggests the ambition and complexity of his intention.

AIR 5, Will Wilson

Downriver, Will Wilson

Eyedazzler Oxford, Will Wilson