Andrea Polli N.

Visible Sound — Brief, but Cool

Andrea Polli’s N. is the first work you see when visiting Visible Sound, the current exhibition at Central Features in downtown Albuquerque. N. is a circular projection on a wall that cuts across the gallery floor. The projection is not still. The image blinks in a time-lapse staccato, looking, virtually, like every snapshot in the life of snow. Although, it’s more like seasons of snow.

In the headphones you don, you can hear searching, drone-like noises; squelchy frequencies, quiet. It sounds and looks and feels like raw data. And it is. Central Features owner Nancy Zastudil tells me that Polli collaborated with sound artist Joe Gilmore and scientist Dr. Patrick Market to collect the atmospheric sounds and images from the Arctic. The piece—a flickering snowball on the wall—is a glimpse into the dramatic shifts in Arctic warming. The scary thing is that the N. was made nearly ten years ago.

While N. is a well-researched and frightening examination of global warming, in thinking about the theme of the show, I had a hard time understanding the transition from sound to image. And while, from the artist’s perspective, there might be a hierarchy that exists in the work—wherein the video is the eidetic support for the atmospheric recordings—I can’t imagine one without the other. Without sound, the video would still hold the weather information, but it would feel toothless. Sound alone would be a detached, amputated sensorial document without the requisite terrestrial reference.

I listen to the field recordings of Polli’s students at UNM. At this point in Visible Sound, my mind wanders off, and I’m struck with how long “research as contemporary art” has dominated academic and art-institutional models of thinking. Even in the history of sound as material for image-making, artists from Robert Delaunay and Paul Klee to Stan Brakhage and the Whitney brothers have searched for ways to perceive the synesthetic phenomena wrapped up in sound or to effectively translate, or compose, the aural into the visual (ideasthesia). A lot of this has to do with changing technologies, I tell myself. And then I realize there are two other artists whose work I haven’t seen.

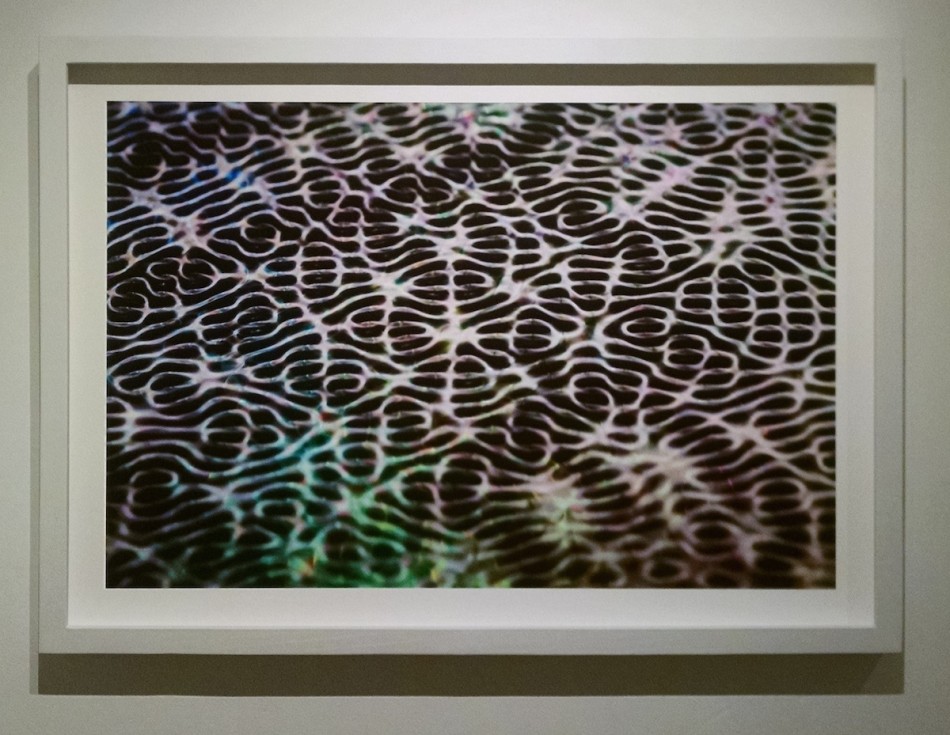

Sasha Vom Dorp’s practice exists in an experimental, trippy space. Using something he calls a Sound Illuminator—made from the nose of a Boeing 727 jet—Vom Dorp’s process involves running different frequencies (in the form of music) through speakers that vibrate a basin of water. The vibrating water is surrounded by either natural light or LEDs in the Illuminator. At some point, he photographs the resulting vibration (of both light and water) and prints his experimental inquiries onto large sheets of watercolor paper. The images are cool, but really I just wanted to see the Sound Illuminator in action—mostly because it reads like a wizard’s name—and bear witness to the PopSci/DIY vibe of the process. In all seriousness, the resulting images are seductive and compelling, even if they sometimes feel like science-center art. But if the role of the artist is to ask questions of the materials at hand, simply in an effort to convert sound into image, then the open inquiry Vom Dorp employs makes sense.

The most intriguing thing about Alyce Sontoro’s sonic weavings is that they actually hold playable sound collages within the woven audiocassette tape fabric. In fact, if you want to hear something cool, you’ll check out her Between Stations album on cdbaby.com and listen to snippets of her sonic fabric recordings. She had a video in Visible Sound that documented a performance where she played an amplified, improvised flute through a standing wave flame tube (Ruben’s tube). Basically, there are flames coming out of perforations in a tube that are affected by the sounds coming from the flute. The video was hard to see, but just the idea of using sound to play with lit propane won the day.

Sontoro also showed two colorful, graphic mode charts, which seemed so far beyond my comprehension and so far removed from their stimuli, that I had to deal with them strictly in their resulting form. Aesthetics, not research, dominated my reading, and while knowledge of the major and minor scales might help understand the origin of the patterns and colors, they didn’t help my enjoyment of those patterns and colors. Research gave way to lyricism.

Visible Sound at Central Features is a condensed and focused invitation to think about the visualization of sound in art. The three artists—Sasha Vom Dorp, Andrea Polli, and Alyce Santoro—and curator Nancy Zastudil have filled the small footprint of the gallery with work that introduces ideas that for the most part translate into interesting visual corollaries. Even in its brevity, it’s a cool, thoughtful show.

Alyce Santoro Installation with Sonic Fabric Scrolls, 2015 and Graphic Mode Charts, 2015

Sasha Vom Dorp Installation

Sasha Vom Dorp 100 Hz Sunlight, Taos, NM, 2014 Archival pigment print mounted on aluminum

Andrea Polli N.