Red Staircase - Spain Turns Abstract Through Finnish Eyes

US Is Still an Art Superpower: TEFAF Report

Just after The European Fine Art Fair (TEFAF) closed its annual event in Maastricht – it is the best and most wide-ranging art fair in the world – the news came that hedge fund king Steven A. Cohen of the embattled SAC Capital Advisers bought Picasso’s Le Reve, a 1932 portrait of the artist’s blonde mistress owned by Las Vegas mogul Steve Wynn. The price was $155 million.

The Dream (Le Reve) – The Buyer (Steven A. Cohen — Two More Marie Therese Portraits by Picasso Were at Gagosian in Maastricht

The picture of a sleeping Marie-Therese Walter, a teenager whom Picasso first met at a department store, wasn’t sold in Maastricht – although two paintings of her were offered at the Gagosian Gallery at TEFAF, for $8 million and $12 million — but the deal confirmed two trends that were identified in a much-anticipated survey of the art market that TEFAF unveils every year.

Americans are once again the most important group of buyers on the market, we learned at TEFAF, and the highest prices achieved tend to be for a small group of artists – Picasso, Monet, Cezanne, Rothko, Warhol, Richter, etc.

How do we know who’s buying art, and who’s buying what?

The Global Art Market: With a focus on China and Brazil, an informative new volume with a cumbersome title, was prepared by the art economist Clare McAndrew, as she does each year for TEFAF. McAndrew, of the firm Arts Economics, released her report on March 15 in Maastricht. She said this year that Chinese buying has receded, relatively speaking, and that the United States has retaken first place among art-buying nations.

As the $60 billion world art market contracted by 7% in 2012, sales in China fell by more than 20%, and sales of art in the US inched up 5%, giving the US 33% of world market share and leaving China with 25%.

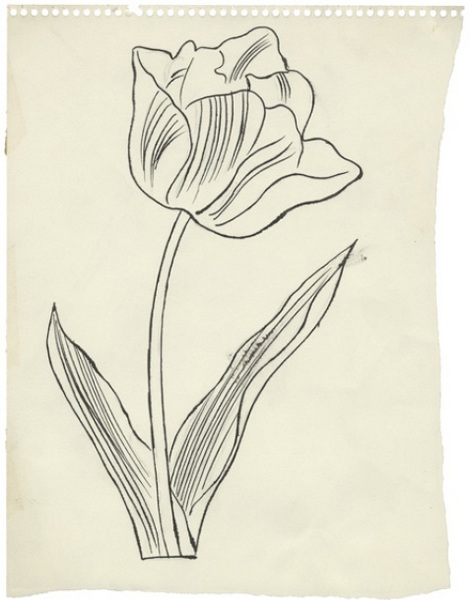

As Mao (almost) Said, Let a Hundred Warhol Flowers Bloom

“The main reasons for the deceleration in growth,” McAndrew concluded, “were both demand factors (including a slowdown in economic growth and continuing liquidity constraints), and a reduced amount of high quality, high priced works coming on to the market.”

The term “high quality” refers to the prevalence of fakes in what had been a Chinese buying stampede, a problem that may have driven some Chinese buyers at the top end of the market to the rigorously-vetted booths at TEFAF.

The Chinese will be back, not just at TEFAF, where Chinese antiquities were being sold in abundance by the dealers Ben Janssens and Gisele Croes, but throughout the West. The decline that McAndrew noted still leaves China ahead of the United Kingdom, and China remains a major art market, with vast potential for growth internally and a small clutch of collectors who shop for non-Chinese art outside of China. With those buyers in mind, TEFAF has announced that it will hold a fair in Beijing next year.

On to China – the Dutch Dealer Ben Janssens

TEFAF’s other major assessment of the art market, offered by Thomas Galbraith, director of global strategy for artnet and affirmed by McAndrew, was that activity in the market at the highest prices targeted a relatively small number of artists. Here is how Clare McAndrew put it: “Economic dynamics and political uncertainties have produced volatility in many asset markets with a ‘flight to safety’ and a premium on blue-chip stocks and low risk assets. A similar picture has emerged for art, with the heaviest buying and best performance concentrated at the high end of the market for the best-known artists.”

TEFAF Seminar Participants – Clare McAndrew (second from right) and Thomas Galbraith of artnet (left)

You could see evidence of that “flight to safety” at TEFAF, with crowds gathering around a Velasquez portrait for $14 million at the booth of Otto Naumann, and constant attention paid to An Episode from the Conquest of America, a scene by Jan Mostaert of a battle between European troops and “savages” that is said to be the first European painting to depict the New World. The price was also $14 million. The “flight to safety” was also there in early drawings by Andy Warhol from his fashion period at Daniel Blau, a revelation to those who had seen too many soup cans. Even Old master purists stopped by.

High values? In relative terms, these pictures were affordable for the super-rich, but priced high for the many institutions that traveled to Maastricht for a museum-like fair experience.

But Steven Cohen’s purchase of Le Reve drives home another lesson from Clare McAndrew’s TEFAF report. Note that Steve Wynn had arranged to sell Le Reve to Cohen in 2006 – the deal was reportedly done, at the price of a mere $136 million, until Wynn put his elbow through the Picasso canvas when showing off the picture to a group of visitors that included Norah Ephron and Martha Stewart. (Wynn, who suffers from advanced retinitis pigmentosa, is blind.) At the time of that mishap, the $136 million price seemed outrageously high. But bluechips being bluechips, a work by Picasso, from one of his more accessible periods, even if the damaged picture was stitched together, is more valuable now than it was in 2006. Is the lesson here that you can’t elbow the best art – or the richest buyers — out of the marketplace?

More of those rich buyers are coming from China and Brazil, the TEFAF report tells us. Yet while the Chinese buyers tend to buy in China, Brazilians with the funds to buy art (High Net Worth Individuals, or HNWIs) tend to be buying outside Brazil, which now represents only 1 % of the world art market – low because of restrictive taxes on art imports, and because Brazil’s rich buyers represent a tiny sliver of its population.

Economist Clare McAndrew stresses that New York and London will still be the most important and the safest places to by art. Even in the unregulated art market, controls on the trade in those cities are among the reason why wary buyers are there.

“While China’s emergence ended the duopoly held by London and New York for over 50 years, there are still many reasons why these traditional markets will remain dominant centres for the trade,” McAndrew writes in the TEFAF report. “One is the existence of a strong upper middle class which gives depth to the trade. More importantly, they have highly developed cultural infrastructures, including networks of experts, institutions and a wider range of ancillary services to support the art trade. Furthermore, they are among the most transparent and regulated centres for the trade, where the legal and fiscal systems along with various commercial codes offer a level of protection and guarantees to both buyers and sellers, while providing incentives to boost a healthy inflow and outflow of art. The maintenance of an open trading regime has reinforced their positions as entrepôt markets, where art is as likely to be bought by HNWIs from emerging markets as it is by local collectors.”

A middle class, a cultural infrastructure, and market transparency are all under siege in the US today. Now that they are identified them as underpinnings of the art market, will those underpinnings that sustain the art market in the US weaken, even as the art buyers in the top 1% of the US economy prosper? Somehow I sense a new theme for a global art market report. TEFAF 2014?