Filmmaker Stan Brakhage Inspires “Visual Rhythm” at BMOCA

Visual Rhythm at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art (BMOCA) eases viewers into the world of experimental film, video and digital art—an experience that can be immersive. The exhibition links recent directions in new media art to earlier artistic explorations—primarily those of experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage (1933-2003).

Brakhage is considered to be one of the most important figures in 20th-experimental cinema; he liked to call his work poetic film. “In the poetic form, more so than literature, rhythm, color, forms and sensorial effects become the working materials that incarnate the content, inseparable from the experience,” he told an audience in Montreal in 2001. Raised in Denver, Brakhage dropped out of Dartmouth College to make films. He attended the San Francisco Art Institute (California School of the Arts) then moved to New York where he became a student of John Cage (who did the music for his first color film, In Between) — and collaborated with Joseph Cornell. While Cage was an important influence, only 27 of Brakhage’s 350 films were produced with sound. Brakhage created films that were about visual “chance” in the same way that Cage’s music was about compositional “chance.” This is most evident in his film Dog Star Man.

Returning to Colorado in 1964, Brakhage commuted to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago where he taught film history and aesthetics, ending his teaching career at the University of Colorado, which now houses the Brakhage Center for the Media Arts (and an annual symposium in “experimental narrative”).

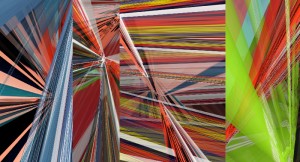

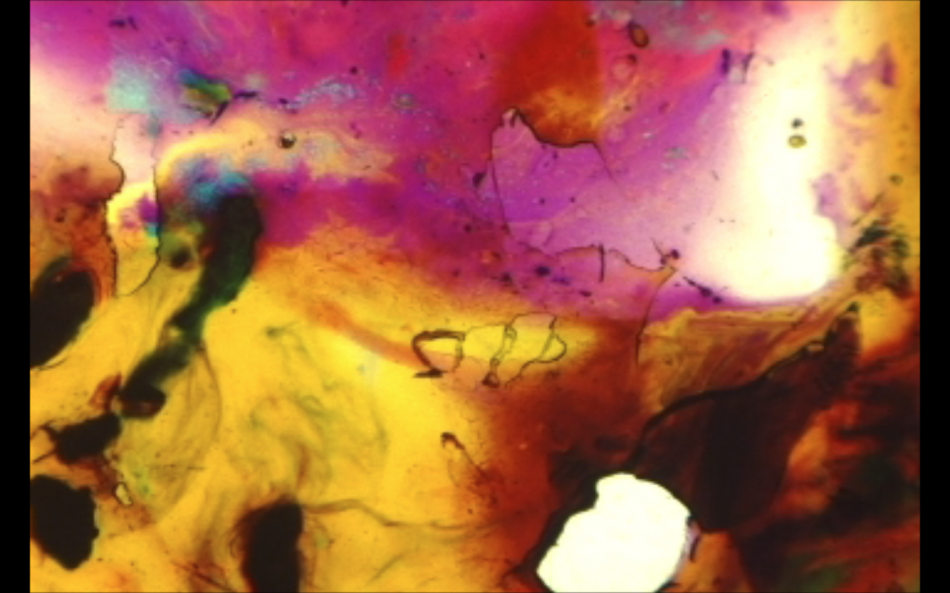

Brakhage’s presence in Boulder was legion; some even remember him drawing on strips of film on Pearl Street, BMOCA associate curator Petra Sertic said. An example of these miniature abstract paintings on display in the main gallery, is itself a tiny work of art. Turn around and you realize that the film being shown nearby was created the same way. The museum has crafted a set-up to be able to show Brakhage’s 1999 16-mm films Persians 1-5 on a continuous loop. A large box allows the film to loop up and down and viewers can see that the strips are painstakingly hand-painted like the smaller framed example. Persians 1-5 are silent, except for the whir of the projector. They present a colorful exploration of line and shape. The experience is near visual overload and this is only the beginning.

Sertic told me “Visual Rhythm” was built around Brakhage and the question, “what is happening now in experimental film and new media?” (AdobeAirstreamRadio interviewed one of the show’s artists, Rick Silva, on this very question. Link here.)

Visually at BMOCA, the answer presented is about a dozen works by national and international artists, several with a strong Colorado connection. Some created new commissions, such as Golden, Colo. -based Rob Miller whose Fuse is an interactive installation that allows viewers to manipulate two open-source videos, accessed through the Internet, using a control panel and computer touch screen to create an original composite video that is then viewed as a projection on the adjacent wall.

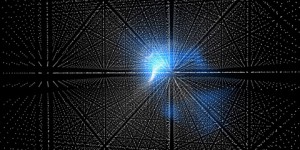

In the back of the space on the lower level, another work is interactive, too. Fernando Velázquez who lives in Sao Paulo, Brazil presents Mindscapes, which also features a touch screen with no text or instructions, that allows the viewer to control the projection. Velázquez composed an algorithm to render possibilities and speculations about the surroundings that shape our view of the world, how we build awareness and how we convey memory. It’s landscape in relation to brain activity. His interactive installation is accompanied by six short videos and two Plexiglas prints that capture a moment within the computer program. For Velázquez, art is no longer about referencing what we see, but exploring the internal workings of the human mind.

The quirks of the human mind are on display in the upstairs gallery in David Fodel and Paco Proano’s Channel. Another interactive installation created from embedded LED lights, corrugated polycarbonate panels and synchronized sound. The sound and lights speed up as viewers get closer and the software interprets brain data collected during photosensitive epileptic seizures. The lights and haunting sound of this installation follow the rhythm of the original seizure. This type of seizure is triggered by repetitive visual stimuli.

The repetitive visual stimuli of this exhibition may not be seizure inducing for most viewers; however all of the works are at least experiential if not interactive. They do not attempt to convey meaning, yet all remain poetic and true to the essence of Brakhage’s work, which often revealed the universal in the specific. Brakhage pushed cinema to pursue the liberation of the eye, to see in ways previously unimagined. Several of the artists in this exhibition have taken up that mantle and are pursuing it with 21st -century technologies and tools.