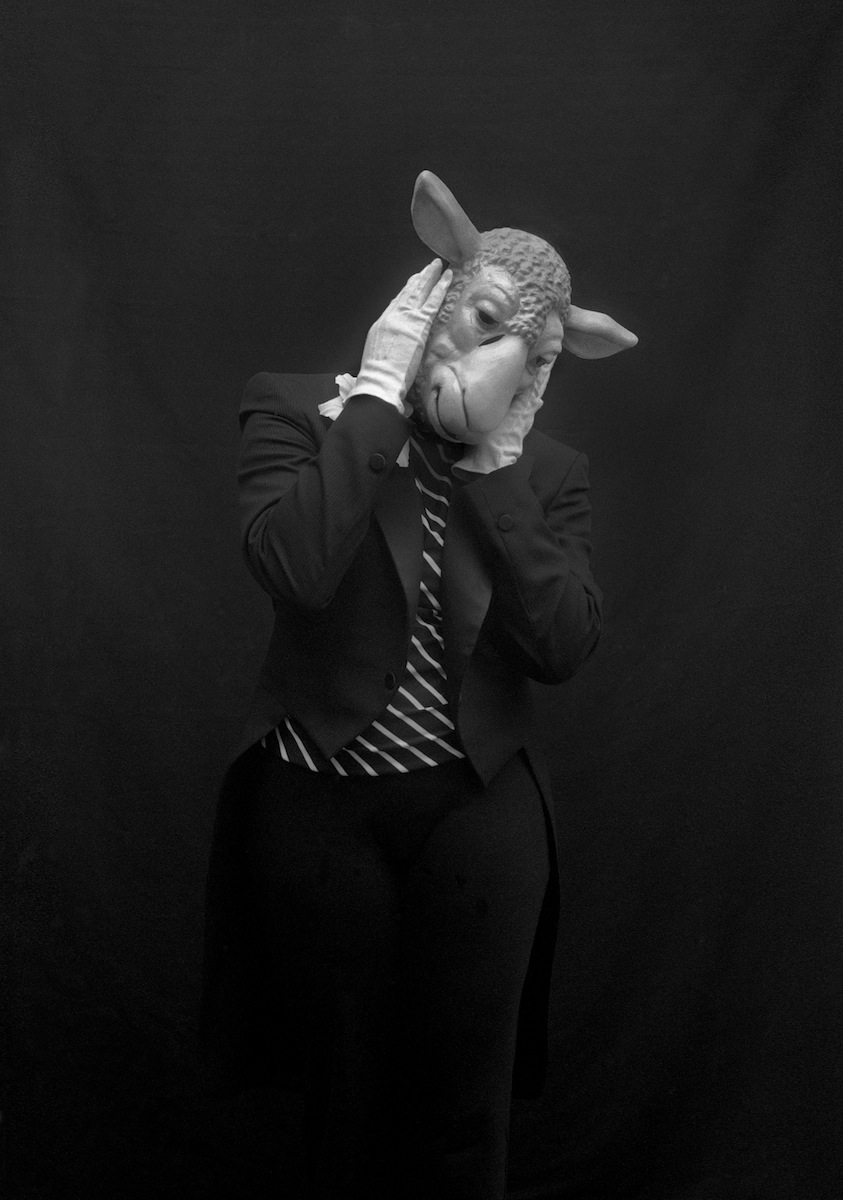

Carrie Mae Weems, Lincoln

Prospect.3 Opens in New Orleans with New Staff, New Philosophies

As Prospect.3 gets under way in New Orleans (opening to the public on October 25th), the state of the conversation about contemporary art biennials keeps re-telling a story of the festival staircase and the critical railing that biennials have to ascend and grasp at the same time. Biennial or bust? (“What’s the point?” wrote the Art Newspaper in 2011.) Battle of the Biennials ensued in The Economist in 2012. The issue had actually gotten a poetically existentialist description in a critical piece that Carol Becker, then at Art Institute of Chicago, penned in ’99 (“The Romance of Nomadism.”) Biennials were exhausting (for well-heeled art pilgrims), expensive (for the producers and everybody else); and you forgot where you were.

This all had arguably started when Peter Schjeldahl coined the term “festivalism.” (“Festival Art: environmental stuff that, existing only in exhibition, exalts curators over dealers and a hazily evoked public over dedicated art mavens.” ) Let’s pull out that important phrase: “a hazily evoked public,” and fast-forward to the spleen that art biennials seem to evoke lately. Jerry Saltz writing on behalf of the sensorium called this year’s Whitney Biennial, “optically starved, aesthetically buttoned-up (and) pedantic.”

Who would walk this road? And why does the road still have so much skin in the game for smaller art cities — palpably as the “Prospect 3: Notes For Now” edition of the New Orleans “Prospect” biennial, previews next week?

Whether visually and materially juicy, or exaltations of admin over aesthetics, biennials do live in an economic bullseye, if they succeed to draw bodies. The first Prospect, the justifiably famous P.1 in 2008 — three years after the storm of Hurricane Katrina — drew 90,000 to a city still under water emotionally if no longer literally. Prospect’s founder was curator Dan Cameron (now at Orange County Museum of Art). Cameron had also produced P.1’s successors, Prospect 1.5 and Prospect.2. He emceed P.2’s opening in 2011 with the simultaneous announcement that he was stepping down.

Hence: all new management. P.3’s Executive Director Brooke Davis Anderson hails from previous museum posts including the American Folk Art Museum in New York and LACMA. She told me by phone from New York that she had been recommended for the job by Artistic Director Franklin Sirmans. He heads up the contemporary department at LACMA and has previously worked at the Menil, and consulted to P.S.1.

What Anderson and Sirmans have faced, as the new management team, include — by each of their accounts — challenges to produce an international show that lacks a single venue of its own, and therefore exists in synchronous partnership with a whole bunch of presenting organizations in New Orleans (18 of them.) Anderson acknowledges that in challenge lies opportunity.

“We don’t have a venue, unlike SITE or Venice. We don’t have a home of four walls. In some ways that gives us a lot of freedom, that we depend on all our partnerships to have a place to produce this project. Partnerships lead to a more diverse and richer audience. For me, that’s always an ultimate game. And also partnerships mean projects are more complex and richer and deeper, because partnerships are born out of compromise, so you’re consistently trying to make sure everyone feels they got what they wanted.”

Brooke Anderson

Sirmans said that he has learned “the most” about the city of New Orleans through visiting the artist-run collectives that have sprouted up in the St. Claude Arts District — venues (some of which we’ve covered at AdobeAirstream) including Parse Gallery, The Front, Good Children. “That’s where I’ve learned the most about NOLA, in those artists-run gallery spaces,” Sirmans said by phone from Los Angeles.

If part of what identifies those loci has been a democratic, self-organizing principle, to which I was introduced by artist Rachel Avena Brown, Sirmans noted that he has hugged a close line between directing an international show of contemporary art, while recognizing the requirement to fully locate the exhibition in New Orleans.

“My approach is that, in order for any of these types of biennial exhibitions to be successful, they have to be firmly located in where they exist and where they come from. They have to show me something of where they are from. But first and foremost, [P.3] is an international show of contemporary art. From the beginning it had to have something to say about New Orleans, while also being a vehicle for international discussion.”

Franklin Sirmans

As Anderson has had the reality of audience development on her mind, projects that have ensued — and generated philanthropy — include P.3 Reads, which will involve biennial artists visiting the 12 library branches around the city and engaging with a local in discussion about a favorite book. This literary structure nods to the fact that Sirmans says he has grounded his thinking in a return to Walker Percy’s 1961 novel, The Moviegoer. While P.3, except for the understated “Notes for Now” subtitle, lacks any overtly discursive theme, Sirmans stressed that “theme” is very much part of what he has hoped to align. To bring into New Orleans, as Percy did in his book, internationalist philosophy. While also: “Locating the fundamental structure of the experience specifically in New Orleans.”

“You don’t really experience the exhibition unless you go through the city of New Orleans, and that is just as important as the exhibition.” (Sirmans)

Sirmans said that the opportunity to work with venues found him at first just thinking expansively about how many artists he could include. The ones who have had palpable pre-existing artistic relationships whether known or just being uncovered with this show, are numerous. Some are also poignant, such as works by the “composer of art and sculptor of music,” Terry Adkins, who died last February.

Works by Jean-Michel Basquiat (hashtag: #BasquiatandtheBayou) will be coming to NoLa’s Ogden Museum and for the first time, says Sirmans . “‘I can’t believe this hasn’t happened here,'” he explained, telegraphing his thinking. “It’s too specific here. He made so much work about the space of the south and about the Mississippi River in particular. He also was here for Jazz Fest shortly before he died in ’88.”

Jazz Fest recurred in my conversation with Anderson.

“When I was hired, the board said we want Prospect in 20-50 years generationally to be as big as New Orleans Jazz Fest. To be as important. To be as much of a contributor. As much on everyone’s radar. As revered by out-of-towners as it is by locals.” (Anderson)

Here is a small preview of some of the artists included in P.3. Satellite exhibitions include one being loosely called P.3 Plus (P.3+), including this one just covered at NoLa. com of a gun-buyback program and free recording studio. Below: some of the artists in P.3.

Terry Adkins

Sirmans asked the question,”Why not put the spotlight on them?” about the works that in 2009 Dillard University commissioned Terry Adkins to create, Ezekiel Double Drums and Ezekiel Wheel. In their making Adkins engaged with W.E.B. Dubois’, The Souls of Black Folk (from Bartleby: ”

Herein lie buried many things . . .

Sirmans said he saw the opportunity to pair Adkins’s work with work by William Cordova at Dillard, exhibiting Adkins’ influence on the younger artist.

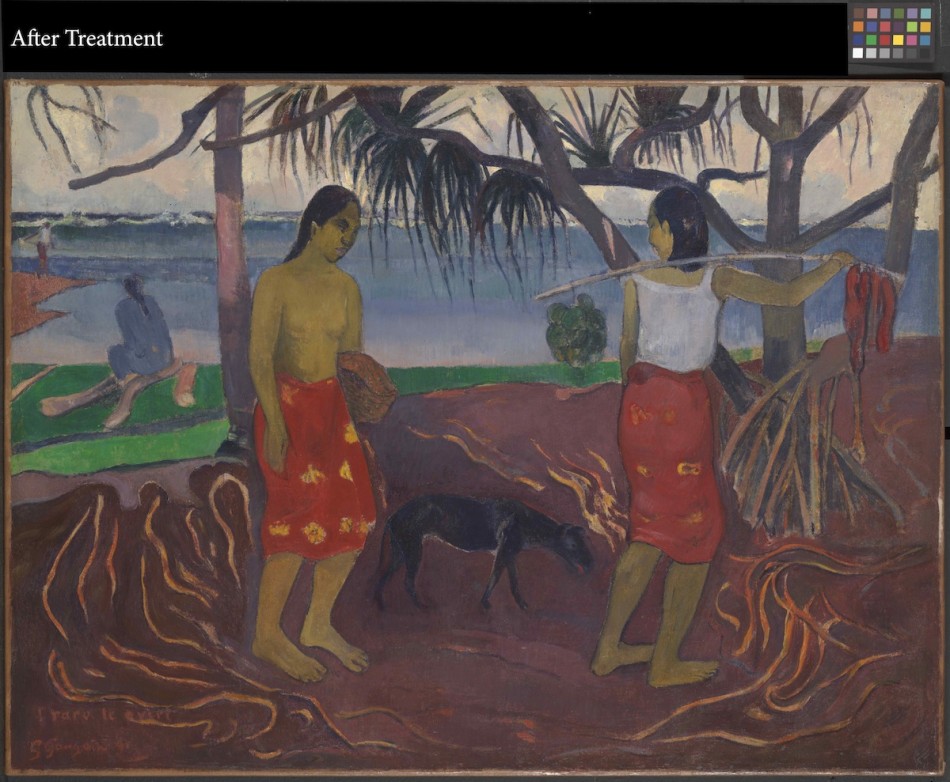

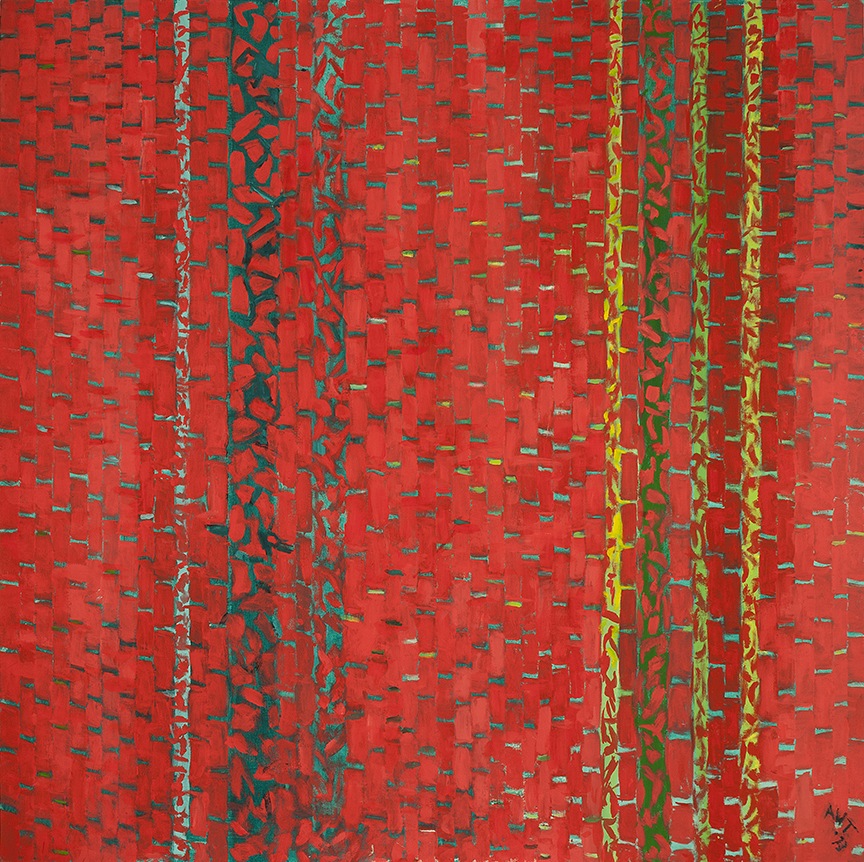

Alma Thomas

Artist Alma Thomas part of the Washington Color School, exhibited three times at the White House while she lived. (The Obamas “de-listed” a Thomas from 45 works they were going to borrow from D.C. institutions.) Sirmans connects Thomas into a discussion about abstraction that is also a “a conversation on representation and identity.” Her work will be seen at New Orleans Museum of Art, as will that of modernist Tarsila do Amaral and post-Impressionist Paul Gauguin. Thomas was born five years after Amaral. Gauguin starts the conversation “of artists born in the 19th century.” Now that sounds a vital key for New Orleans.

Shigeru Ban

The Pritzker-prize winning architect who designed the new Aspen Art Museum, is well-known for his many works of ecologically sensitive, refugee architecture. Here Sirmans says that P.3 will certainly let people know about the existence in NoLa’s Ninth Ward of a house he designed for a family who had lost their house to Katrina. But it’s the Shigeru Ban exhibition at Longue Vue that will focus on other of his relief projects, borrowing objects “directly out of the exhibition in Aspen.”

Carrie Mae Weems

In the decade since I ventured to New Orleans for Artforum in 2004 to cover Carrie Mae Weems’s installation commemorating the bicentennial of the Louisiana Purchase, at Newcomb Gallery at Tulane University, a lot has happened — including that Weems won a MacArthur fellowship or “genius grant.” Sirmans said regarding the work she will exhibit at P.3 that it is all new work, and “an expansive installation” that will occupy the McKenna Museum. “We started with a conversation a long time ago, and because of the past points of reference you mention, I gravitated to that idea that somebody who has had such an engaged experience there (in New Orleans), I felt she was going to teach me along the way.” The significant installation, Sirmans said, references her relationship to music.

Weems has also created a limited edition print with Carolina Nitsch Editions, Untitled (Ella on Silk), 2014, as a P.3 fundraiser.

Shigeru Ban designed a residence for people who had lost houses in Hurricane Katrina in the lower Ninth Ward

Jean Michel Basquiat, King Zulu

Paul Gauguin, Under the Pandanus

Alma Thomas, Azaleas

Alma Thomas, Carnival

Carrie Mae Weems, Lincoln

Carrie Mae Weems, Missing Links Sheep