Maria Park, CN shelf object (7,8.,9,10),2010; acrylic paint on Acrylite; 7"x7"x7" each cube

Painters Point the Way at Richard Levy Gallery

Painting, inextricable from human and social evolution, continues as a ready target for provocateurs lobbing the contention that the medium’s expressive force of action has finally achieved irrelevance to hands-free digital imaging. The conversation generated within “That’s Where You Need to Be,” a juried exhibition at Albuquerque’s Richard Levy Gallery, refutes such critical claims and even co-opts them with a demonstration of how the act of painting remains married to elemental expressive instincts.

Highlighting recent work by William Betts, Xuan Chen, Maria Park and Willy Bo Richardson, the show surveys how each artist employs abstract means to delve into the effects of color, space, and the current course of our evolution (or devolution). The artists’ references and methods are diverse but find frequent overlap. Richardson stretches vertical bands of color so intense across each canvas that they seem to crackle like neon. He has described his act of painting as a sort of meditation, a give-and-take with gravity and the universal laws that determine our experience of the physical world.

His rhetoric flirts dangerously with New Agey vagueness, but the experience of Richardson’s paintbrush grappling with and against fundamental physical constraints is immediate, intimate. The stripes are singular yet interrelated. Gestural under-layers with both dark and light elements offset his more disciplined vertical strokes — those so saturated that they vibrate, gripping the viewer, and each canvas’s humming field suspends the sensation of time.

Xuan’s “Screens” series at the opposite end of the gallery bookends Richardson’s work, further concretizing the show’s larger discussion of color and space. (Both artists live and work in New Mexico, which perhaps contributes to their mutual dialogue, planned or not.) Her process first plays out on a computer screen, where Xuan creates multiple geometric color fields. The resulting images are then painted onto a three-dimensional grid of cut aluminum panels, also referred to as “screens.” Thus, the same flat colors that took form in a computer’s electronic 2-Ds are reborn into tangibility, and like their digital counterparts, each of these built screens is ethereal. They seem to float, some casting sheer rainbows on the gallery’s white walls. While Richardson’s use of color induces transport from physicality, Xuan’s emphasizes it, transforming colors into mutable objects.

Park uses actual bookends, speaking of these brackets that enclose a sequence of something, to discuss related notions of how technology intercedes with our perceptions and interactions, particularly in regards to the natural world. Excerpted from her extensive “Counter Nature” installation, an acrylic painting and two pairs of painted Plexiglas cubes on shelves of nature-themed books are themselves excerpts. The flattened images are drawn from the shapes and contours of “natural” places that are increasingly domesticated and sanitized. In Park’s own words, her graphically flattened nature overlooks, cut through by parking lots and other human intercessions, are “landscapes for the inertial (sic) tourist.”

Park’s precise handling of the paint also imposes hard cuts, strict boundaries. There’s indication of individually textured trees, foliage, rock outcroppings and sharp shrubbery, but her approach flattens even those into a kind of graphic wallpaper. Wilderness areas are therefore converted not only into a scene easily swallowed by a tourist’s camera but into an abstract pattern that might be worn or stamped in serial reproduction.

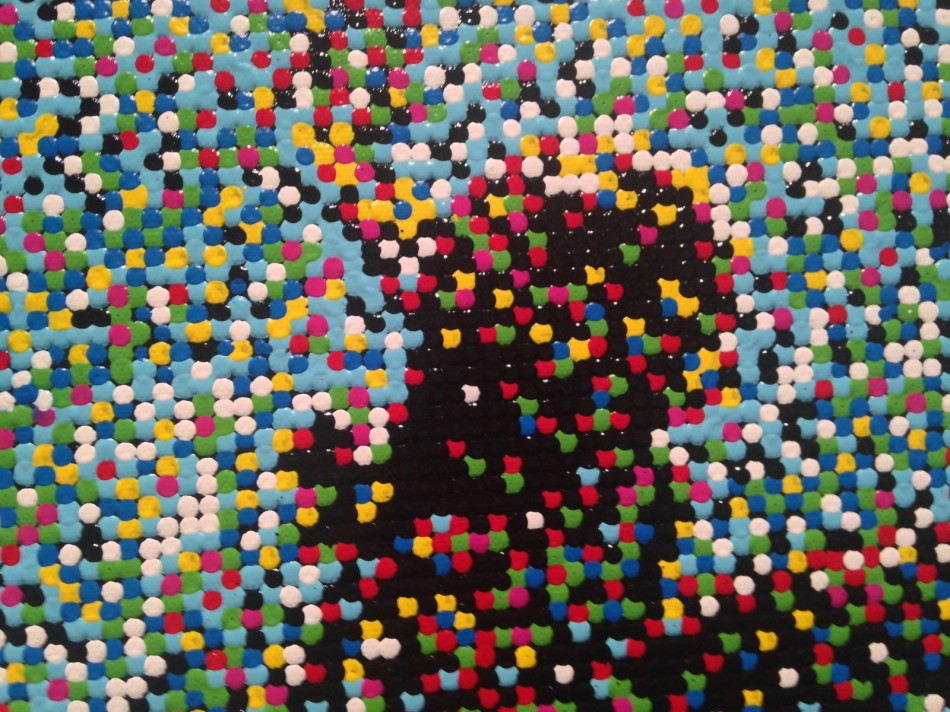

Meanwhile, Betts’ pointillist scenes reference social scenery as emotionally flat as Park’s botany. Betts’ subjects and technique — crowded, sunny beaches and pool bathers emerging from a field of color points — humorously echo Seurat and Degas. But Betts’ methods highlight how far our heavily industrialized, heavily surveilled world really is from those artistic predecessors. He has outsourced the act of painting by programming his pieces into a computerized machine tool; it mechanically places the dots of paint, executing for him. The process reprises old questions: Where is our individual agency in being hypnotized by this strange dance of perceived light and image? Is this holographic reality?

Levy Gallery’s assembling of these artists first demonstrates how the impulse to manipulate paint retains relevance today, both interrogating and incorporating new technologies. Emitted in the midst: quiet flashes of insight about the slippery, ultimately illusory nature of perception and representation. The compositions trigger an upending of the idea that there’s a clean division between handmade and hands-free.

Xuan Chen, Screen Set 2 #7, 2014, mixed media on aluminum panel, 9″x12″x3″

Xuan Chen, Screen Set 2 #9, 2014

William Betts, Swimming Pool IX, 2014, 15″ x 20″, acrylic on canvas

Detail, William Betts. Photo: Margaret Wright

Detail, Willy Bo Richardson, Music to Drive To #9, 2012, 53″ x 114″, oil on canvas. Photo: Margaret Wright.

Willy Bo Richardson, Music to Drive To #9, 2012, 53″ x 114″, oil on canvas

Maria Park, CN Shelf Object 7,8,9,10, installation view