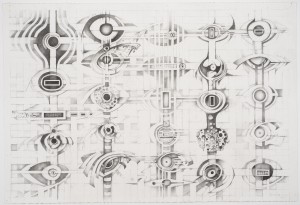

Lee Bontecou Untitled, 2011 Pencil on paper 30 x 44 inches Collection of the artist © 2013 Lee Bontecou Photo: Paul Hester

Letter from Houston: Lee Bontecou at the Menil, Dan Gorski at Wade Wilson

Lee Bontecou: Drawn Worlds on view at the Menil Collection through May 11th, is the first drawing retrospective for the artist who when “rediscovered” for big museum shows a decade ago was rediscovered for her meaty, muscular work: large-scale sculpture that the artist largely concentrated on between 1958 and 1967 before having a child sidelined the sculptural practice.

Drawings, however, Lee Bontecou never stopped making. This show organized by Menil Curator Michelle White (under the auspices of the Menil Drawing Institute) reveals work done deeply and broadly in a medium the artist has worked in far longer than sculpture.

Made between 1958-2012 are 76 works in the show including some notebooks from her late 1950s years revealing things she found, was excited by, and the ensuing scritching obsessions of the repetitive-compulsive draftsman.

After studying at Art Students League (NY) Lee Bontecou went to Rome on Fulbright fellowships in 1956 and ’58. I was reminded in re-learning this factoid of one of my favorite artists, Jay De Feo, who also got to Europe briefly from Berkeley in the ‘50s and would later say it was because her name had led her to be mistaken for a man. When The Rose (1958-1966), De Feo’s monumental sculpture eight-years-in-the-making had its resurgence at 2012 retrospectives in California and in New York at the Whitney, it was interesting to see the re-assessments of what overlooked women artists had been doing at mid-century. De Feo and Louise Nevelson were the two women curated into MoMA’s 1959-60 show Sixteen Americans. It has been suggested that had the Rose been finished by then, perhaps De Feo’s artistic fate would have been different. (Nevelson with her elaborate wood sculpture remained through the many decades of obscurity for Bontecou and De Feo the turbaned grande dame-magus among the New York boys’ club, her dark eyelids and brows as dramatic as her large-scale work.)

When Bontecou’s sculpture emerged in a public way in 2003, the inevitably reductive ways of art history tended to describe the welded steel frames covered with recycled canvas (such as conveyor belts or mail sacks) and other found objects as sprung from the head of Zeus. When I first saw them at MoMA I harked to a felt connection between Rauschenberg’s performances at Black Mountain College on roller skates with parachute fabric and these eye-like deep aperture spaces that owed something to tail fins and something more to the sublime eye sockets of Easter Island.

In this vein, coming upon the drawings was incredibly interesting in what it showed about how fascinated Lee Bontecou was and is by the anatomy of fish — their vertebral complexities, their fins and cheeks, the negative space of whorls, pocks, dilations, compressions and the sense of biologies and even cosmologies pulsating in a bigger cosmic ether. Studies of wave forms and what might be the tail of an eel, or the labia of what Miss O’Keeffe, wanting to avoid anatomical associations, titled “Music” in a painting of similarly cave-like apertures. Graphite-and-soot on paper in a particular 1963 for Bontecou seemed ominous, as if she were divining that the blackness held all colors shadowing a void below. Hemispheres of hell? Horizons influenced by the Cuban Missile Crisis?

These are questions that perhaps scholarship hasn’t caught up to yet but that make shows like this one unmissable — if you don’t have to miss them.

Dan Gorski: Hard Edge: Then and Now

Wade Wilson Art

Dan Gorski’s work Fourth Down was included in the original Primary Structures show (1966) at Jewish Museum in New York. On March 14th this year the Jewish Museum revisits the epoch with an exhibit, Other Primary Structures. The 1966 version introduced the term minimalism to new art as it declaimed, hey you painters, move on over, we are here. The we included Donald Judd, Robert Morris , Mark di Suvero (and Carl Andre, Tony deLap, Robert Smithson, Larry Bell, Douglas Huebler, John McCracken, Anne Truitt, etc.) whose work was curated into 10 galleries at the museum. Donald Judd who went on to pen some lasting manifestos rejected the label minimalism; other ones that magazine critics for the newsweeklies Time and Newsweek threw around in May and June issues of 1966 were “ABC art” and “reductive art.” “Minimalism” stuck.

Lucy Lippard in her review eschewed the naming craze, but wrote about a “confusion” of styles.

Dan Gorski has had a significant career as an artist and in art education (he taught at Glassell School of MFAH from 1990-1996), has had residencies at Yaddo and in Japan. His exhibit at Wade Wilson Art presented some work that emerged from his MFA practice at Yale School of Art (1964) and in the few years afterwords.

The works are riotously colored in tones that evoke dresses Twiggy wore (French kiss) or psychedelic album art (I Shot the Sheriff) and obsessions with color-chart spectral effects and even trails. Fast forward to more recent studio work in muted tones of almost white slip scored with black lines (named Levelland for the Texas music town); a musical through-line persists. By far my favorite were the sculptures ranged against the wall. Fourth Down remakes clips that look like they could fall on their sides and be playground objects — gigantesque burlesque hooks in candy-striper red and white. The show can evoke a nostalgia though is not explicitly nostalgic especially when holding in mind what is being presented today by sculptors like Arlene Shechet or artists included in Chesterwood’s 2012 sculpture show in Brooklyn. That Dan Gorski’s work can warm up a room and play ping-pong with a history of “primary structures” is clear.