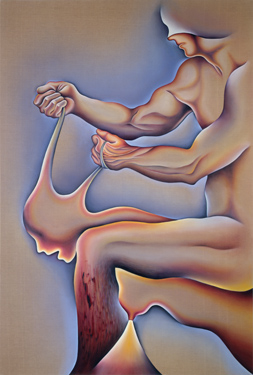

Judy Chicago, In The Shadow of the Handgun, 1985

Interrogating Heroic-Ness – and Judy Chicago’s Cultural Powers

July 7th at St. Francis Auditorium found artist Judy Chicago sharing a stage with art historian and queer theorist Jonathan D. Katz, to discuss a body of her work that she began in 1982 and had not shown publicly in more than three decades before the current exhibit, Reviewing PowerPlay, went on view at David Richard Gallery in Santa Fe, June 29th. (Through August 11.) The painting above sold to a major US collector of feminist art last week, for $300,000.

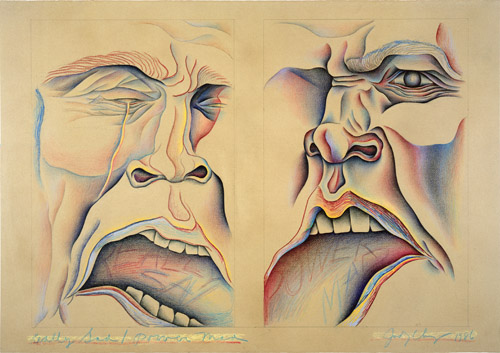

Judy Chicago, Crippled by the Need to Control, 1983

An astute observer would have to notice that Chicago’s message – woman’s work toward a re-envisioned male whose body forms tears as well as fists – remains not only current but avidly debated among a group that spanned a 26-year-old art student and a few octogenarians. Also in the audience were members of the board of directors of the Through the Flower organization – for which the reception following the talk was a benefit.

That reception, at David Richard, was a tour of Reviewing PowerPlay starring Judy and Jonathan, with Donald Woodman videotaping the repartee. It digressed from painting styles to the cultural freight of grimaces, penises and whether fingers pointing guns were unleashing sprays of blood or of menstrual blood (among the evening’s more bizarre ad-libs).

Onstage at St. Francis Auditorium, Judy had opined, after Jonathan observed stained-glass (or an appeal to the sacred) in the “tripartite” painting titled Rainbow Man Composite, that that may have been a unconscious prefiguring, of her later work in glass.

Long before Judy holed up in a Canyon Road adobe to work out PowerPlay back in 1982, she was inhibited by “prohibitions” against what a woman artist, or any artist, could show of men in art. She situated the freedoms of the series also to her meeting Donald Woodman; he gave advice, urging on her a re-articulation of what was allowable for men (as she’d done for women, in The Dinner Party. Hear my interview with Judy on The Dinner Party here).

“Performative feminism,”was a phrase that Jonathan Katz, who is a professor at SUNY Buffalo and president of the board of directors of the Leslie Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, used in talking Judy to Judy. He noted the works’ size: from 9 feet wide x 6- to 22-feet tall, and the gamut from featureless male faces brandishing handguns, to intensely expressive mens’ anguish or rage, that bore “labial folds” or scrotal noses. Out came another observation by the artist, credited to her husband, that she’s been “in an adversarial relationship with my myth.”

While the avidity of the cultural-personal sharing at the afternoon event seemed to say Judy’s myth remains a principal issue of Judy’s work, the revelations came not just from the artist and her critic but from a visiting psychiatrist who appeared to relish the opportunity for self-disclosure, among strangers.

Observing the work amid all the sturm over gender roles, its size remains a primary factor of engaging it. A thin silhouette and airbrush mark out the picture plane. The men have super-big hands. When one squeezes out a tear, it’s often more milky than translucent, as if the act of crying can’t quite trade truculence (or seminal fluid) for bloody vulnerability. The works have an energetic field, an intense impression of force, as if what had to transmute from the artist to her figure was a birth of the next very big thing.

Judy Chicago, Rainbow Man Composite, 1984