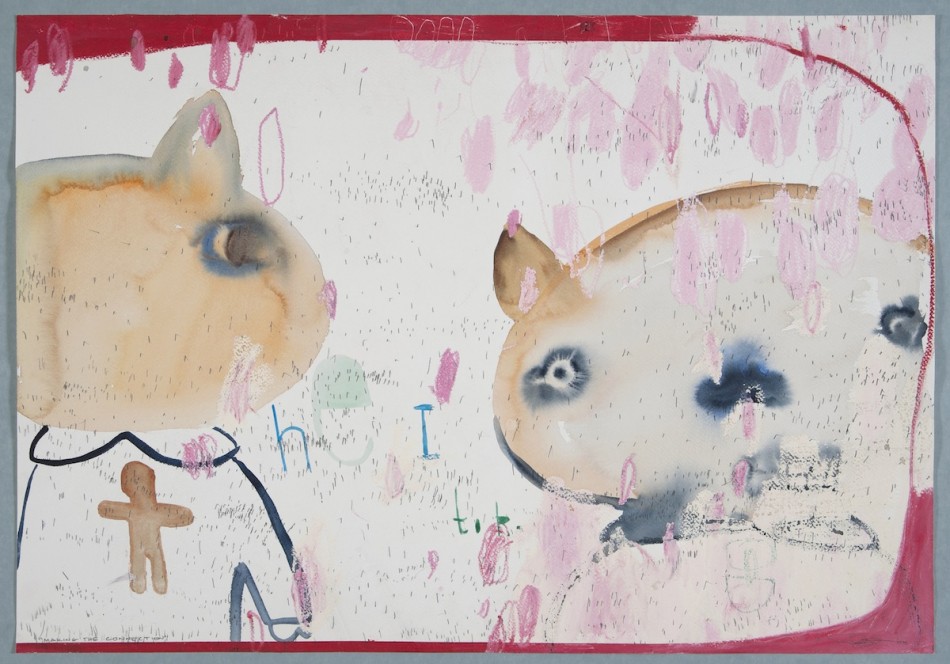

Melanie Yazzie, He Died Before Coming Home, 1994 Monotype

Geographies of Memory Launches Indigenous Art Series

In “Melanie Yazzie: Geographies of Memory,” at UNM Art Museum now through May 17, the artist exhibits an autobiographical map of sorts: a retrospective, multilayered map that softly charts her experiences in nature, culture, and collaboration. Each of these is an area of investigation that has helped cultivate the private catalog of imagery that populates her work.

“Geographies of Memory” is curated by museum director Lisa Tamiris Becker and inaugurates a biennial program of solo exhibitions set to feature the work of emerging or established indigenous artists. Yazzie has cited the importance of her Diné/Navajo heritage in her art practice, and so the work requires, if not a strict reading from that perspective, at least an acknowledgment of its prismatic nature, of the sense that we are seeing the world through the eyes of an indigenous woman living within multiple worlds.

Comprised primarily of prints — relief prints, monotypes, and etchings — the nearly 20 years’ worth of work serves to document the changes in Yazzie’s image making. Understandably there is a varied aesthetic range, which happens over such a long period, and while she may have remained committed to social and political themes throughout, the images vary from the straightforward to the completely indirect and abstract. In that sense, printmaking has provided a controlled creative matrix within which the projection of Yazzie’s exploration of self can develop.

The exhibition, which is mostly grouped by type, begins with a grid of four monotypes, all from 2013 and individually titled “Friends,” “Fairbanks,” “In Evergreen,” and “We Belong.” This group establishes every significant motif in Yazzie’s mature work. Stylized figurative and natural elements rest on a harmonious, semi-transparent ground. Some of the forms reappear in other prints, and all of them are relatively static, sitting quietly in a non-hierarchical shallow space. Some things overlap; others float.

Moving through UNM’s main gallery, these simple strategies grow into a deeper experience of Yazzie’s work that reveals her formal focus on rhythm, repetition and harmony, and her thematic interest in fertility, history, nature, and culture. She uses stripped-down forms that look like textured silhouettes, or pictographs, to carry her symbolism.

In pieces like “Crow” forms are born out of the image ground. The crow’s mouth is open and it walks between hearts or uterine forms, with a pine cone on the right and a burgeoning yucca-like form on the left. The puffed, fertile shapes hold the potential to spawn even more life. The orange and blue are thin and transparent. While easy to describe, the work is still mysterious, its apparent meaning giving way to the unexplainable.

“Early,” “Mid Morning” and “Afternoon” have layered, esoteric logics that ask more questions than they answer. A serpentine line travels over ballooned organs or rocks. There are groups of organized marks and three-digit numbers dotting the entire image. Hinting at cycles and measuring, a specific logic exists, but it is essentially inexplicable and secretive.

There is a favoring of a life’s worth of work over a focus on single hits in “Geographies of Memory.” Excepting some of the more direct images in the exhibition, the incessant repetition of Yazzie’s formal lexicon of esoteric pictographs redirects the quest for meaning away from any one piece, and the audience is instead directed toward the relationships between all of the pieces. A larger cycle of seeing and spacing is therefore intimated between the images, and it is in this cycle that a distant story, albeit still secretive, is woven together. Individual meanings give way to the interconnections within a greater whole.

The strength of Melanie Yazzie’s exhibition lies in her indirect, but highly personal, exploration of change, amplified in the fleeting and intuitive impulses of her monotypes — because that’s where the effect is at its greatest: when her printmaking is embraced as a necessary discursive strategy that carries the shifting arrangements in her larger autobiographical map. Considering she has been traveling and making connections with other indigenous cultures for much of her career, it makes sense that Melanie Yazzie would be the first artist in this series of solo exhibitions. With “Geographies of Memory,” Yazzie has quietly opened a door for future artists to widen the discussion of contemporary indigenous art and issues.

Melanie Yazzie, Making the Connection, 2005

Mixed media drawing