Barry McGee Tags Berkeley Art Museum–and MoMa Acquires Video Games

As I approach the Berkeley Art Museum up Bancroft Avenue my attention’s distracted between a glimpse of sculpture centipeding across the bright green grass (a Calder), and in bright red tag, the word SNITCH, marking the western building wall in elongated upper-case, with a little i dotted by a big thought balloon. It’s the first sign of Barry McGee in the house and even takes you aback initially, as in: Who tagged the art show? The artist did, fool.

The artist who went to San Francisco Art Institute in the ’80s and tagged under the moniker, Twist, was just as engaged with the street as he apparently has ever been with the gallery as sign of (his) upward mobility in the art world. Working for a letter-press printer that was discarding plates daily made for a new-used tableau for McGee. How perspicacious to realize new signified meanings via urban(e) bricolage.

The artist who went to San Francisco Art Institute in the ’80s and tagged under the moniker, Twist, was just as engaged with the street as he apparently has ever been with the gallery as sign of (his) upward mobility in the art world. Working for a letter-press printer that was discarding plates daily made for a new-used tableau for McGee. How perspicacious to realize new signified meanings via urban(e) bricolage.

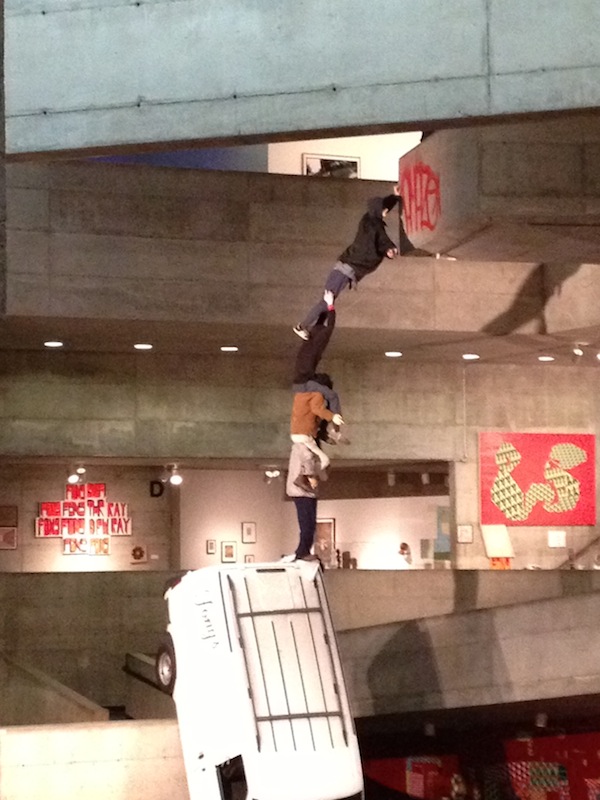

For me, as I stand looking amid the cacophony (so-called animatronic taggers assaulting walls with a ready-aim-spray motion that, yes, makes noise), it’s a little bit like encountering a hip new-world Walker Evans.

McGee faced with the immediacy of the sketch that are his own drawings and prints here composed new walls, yes, on the ground level at BAMPFA, out of the discarded plates. Jackets with the fusillade of now-rusted cans suffice as physical process commentary, the props of action. They’re anti-precious, and as such, charming, even clanking a bit in the mind.

A visitor taking in the sightlines in the brutalist concrete museum with its ramps and sound that permeates under and over as you ascend the levels, gets reminded that intersections where what to call things? Art or design or music revolutions? tend to remain interesting.

Maybe it’s the I-just-did-it aesthetic. McGee, on the city streets of the left coast, marking out a sibilant version of Here’ssssss-Barry.

There’s something at once touching and comical, this sense in a shrine to good taste that you are not alone, indeed always surrounded by the new tastemakers of that which is hardly likely to be condoned in its time. In strict functional terms, to reach a bridge overpass means, literally, standing on somebody else’s shoulders. To reach the overpass of a museum-housed art show means the figures who boost you up are both visible and unseen, as curator Lawrence Rinder appears to understand and even to have had mucho fun with. This fun is what contributes to making the show in this building feel lark-like, a romp, and (as we just learned earlier this week, in reading that MoMa has just acquired, yes, 14 video games to start a permanent collection) — perhaps an underhanded knock at the old building (which I love), even as a new Diller Scofidio + Renfro building is planned for downtown Berkeley. And acknowledgment, trite as it sounds, that museums may be late to the mass-culture party, but they’re throwing a good one.

There’s something at once touching and comical, this sense in a shrine to good taste that you are not alone, indeed always surrounded by the new tastemakers of that which is hardly likely to be condoned in its time. In strict functional terms, to reach a bridge overpass means, literally, standing on somebody else’s shoulders. To reach the overpass of a museum-housed art show means the figures who boost you up are both visible and unseen, as curator Lawrence Rinder appears to understand and even to have had mucho fun with. This fun is what contributes to making the show in this building feel lark-like, a romp, and (as we just learned earlier this week, in reading that MoMa has just acquired, yes, 14 video games to start a permanent collection) — perhaps an underhanded knock at the old building (which I love), even as a new Diller Scofidio + Renfro building is planned for downtown Berkeley. And acknowledgment, trite as it sounds, that museums may be late to the mass-culture party, but they’re throwing a good one.

That’s a whole other subject, including the portion of this exhibit that deals in Jeffrey Deitch inviting McGee, back when, to do something and then something else to real estate. You can’t not think in these loud passages of the various craven-nesses that came together to boost Barry McGee a decade and more ago. And just as the Real Estate show and Fluxus are now considered dead-letter memories of contemporary art history, McGee, following the law of unintended consequences, jumps up to jump down: a gangling kin-esthete, a quick study questioner, an artist holding a rescue note out of what then, in the mid-’80s, was still a very (very) fledgling and very urban revolution. Through December 9th at 2626 Bancroft Avenue, Berkeley.

That’s a whole other subject, including the portion of this exhibit that deals in Jeffrey Deitch inviting McGee, back when, to do something and then something else to real estate. You can’t not think in these loud passages of the various craven-nesses that came together to boost Barry McGee a decade and more ago. And just as the Real Estate show and Fluxus are now considered dead-letter memories of contemporary art history, McGee, following the law of unintended consequences, jumps up to jump down: a gangling kin-esthete, a quick study questioner, an artist holding a rescue note out of what then, in the mid-’80s, was still a very (very) fledgling and very urban revolution. Through December 9th at 2626 Bancroft Avenue, Berkeley.