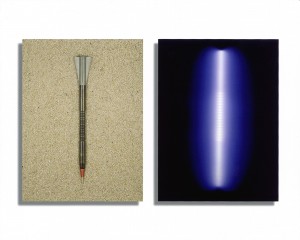

Luca Zanier, Gösgen I (safety lock), 2012 , digital print, 31.5 x 47 inches, ed. 3 of 7

Atomic Surplus — Against Compassion Fatigue

Atomic Surplus runs at CCA Santa Fe through January 5, 2014. I interviewed Erin Elder, CCA’s Visual Arts Director, in early December.

There’s a William Blake line, “where man is not, nature is barren.” Can you respond to that in the context of your show?

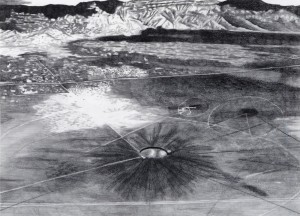

I’m not sure that I agree with this. In the context of atomic testing, for instance, man has made nature — which was once very abundant, verdant — barren. The work of CLUI [The Center for Land Use Interpretation] and Nina Elder evidence this very clearly. So, too, do the works from Fukushima. Also, there is a really interesting sound piece in the show which is a series of recordings from Chernobyl where wildlife has flourished since the meltdown and the subsequent evacuation of humans.

Are there certain assumptions in New Mexico — the birthplace of the bomb — about what a show like this should be like or look like?

I should probably clarify that my curatorial aims are non-didactic. I try to let the work speak for itself and, between the various artist-driven perspectives, the audience creates their own interpretation. While I have a very defined politics around these issues, I thought it was important that the show evidence various perspectives, that it complicate the atomic issue somehow. It’s not a show about destruction as much as it is about cause and effect, the evolution of ideas, weird science, speculation, etc.

Can you comment on New Mexico’s sense of ownership around Black Hole as a material source, or atomic history as a historical source?

I was very conscientious about creating a broad narrative around the nuclear legacy. I wanted to diversify that visual conversation. I invited a lot of young artists, many from other parts of the world, because it seemed important to connect the well-worn World War II histories of New Mexico’s atomic industry to a more complicated, more contemporary global now.

CCA, though, does exist in a local context, or a context where many “local” artists, for lack of a better word, have historically felt that CCA was a spot for their exhibition on place-based issues.

Because the nuclear issue is nothing new to New Mexico or its artists, I felt it was important to diversify the voice. That’s not to say that there aren’t local and regional artists represented. Nina Elder and Greta Young are from Santa Fe. Claudia X. Valdes is from Albuquerque. CLUI is from LA but does work all over the southwest. And we’re producing a dozen or so public programs that involve many local people, poets, filmmakers, historians, as well as artists.

Are people meant to understand a boundary between activism and art in the show (i.e., the Japanese performance art group, ChimPom doing the cheers to the Fukushima disaster…)?

I don’t know if I intend for audiences to understand anything from seeing an exhibition. Rather, my goal would be to ignite curiosity. I think this show blurs a lot of boundaries (science experiments as photographic process, salvage store as creative practice, documentation as art) and I think the act of blurring and the confusion this causes ([are] productive. Atomic Surplus is primarily 2D and video and sound. While much of the work in the show is documentation, it points to another moment that happened, a larger story in the making of the artwork. For instance, ChimPom is a collective who does performance and intervention; [we have] a video of their performance. So too with Peter Cusack’s sound piece or Vanessa Renwick’s video; these artists went on site somewhere (both to highly dangerous places) to create their work. Claudia X. Valdes has made a lot of her work at the Trinity test site, which is only open one day twice a year. Imagine how much planning has gone into her utilization of that one day!

Is there anything new and how would you characterize the “new” when it comes to this atomic subject?

Today I had a group of high school seniors tour the show and they got to talking about generational fear. For them, “nuclear” is super-dated. They don’t feel connected to WWII or the bombing of Japan. They talked about adults being “freaked out” about radiation. They said they’re not worried. I asked if total annihilation was something they’d even considered. Yes, but only at the hands of terrorists. They worry about drones and the environment being poisoned. “The Soviets are over,” one of them pointed out, “maybe there’s less to worry about.” Yes, I believe there is much new to say on these subjects. There’s much that needs to be revisited about the nuclear legacy so that young people don’t just see it as an old folks’ issue; I want them to see it as connected to Homeland Security, to the way we wage war, to the health of tuna fish and the role of government and all of that.

It certainly raises a lot of questions about “history” and the history that people remember personally.

I think when you take a broader scope on the nuclear issue, you see what it did to fear. Fear took on a whole new dimension with the advent of the bomb. Fear of disaster, fear of the invisible, fear of mutation, fear of foreigners, fear of toxic waste, fear of evil world powers; the list goes on.

As CLUI documents spent nuclear fuel facilities, what is “interpreted” anew about both the wastes of atomic warfare and the uses of art to respond to it?

Talk about blurring boundaries — CLUI does that very well. Often they don’t really translate as artists and they don’t really seem to care about that, either. They document much more than nuclear facilities and are trying to create a very comprehensive record of how land is used in the United States. I think this is incredibly important.

The gallery was quite loud with the soundtracks of video. Is that intentional?

Yes, we wanted to create a sense of bleed, that each of the projects connect and overlap in some way. Ideally, each video has its own space that is uninterrupted and, in the interstitial spaces, you get a bit of noise. We wanted to make the audience slightly uncomfortable. I’ve found that in a gallery filled with sound, people are more likely to talk and that is key to this exhibition.

Has there become a sort of fetish around the dangers of the atomic age that doesn’t seem to be going away? Does the work offer a new meaning of “sublime”?

I don’t know about atomic danger becoming a fetish, but I worry that it will become a retro cliché, like some kind of B grade monster movie. The Fukushima meltdown is so relevant and so new and we have no idea how bad or lasting the damage will be. Still, very few people are talking about this.

Does the show intervene, or aim to intervene, in a widespread cultural condition of compassion fatigue?

Yeah, maybe. I’m concerned about a lack of curiosity. I’m concerned about disconnect. I’m concerned about apathy. I’m concerned about believing the story you’re told (and about not getting interested in the stories you’re not told). I would just relate a story I recently read about in Rebecca Solnit’s book Savage Dreams. She talks about the teams of people who were tasked with creating the nuclear waste site at Yucca Mountain. The half-life of the waste they were dealing with is 10,000 years. Humans have barely existed for 10,000 years and who knows if they’ll be around for 10,000 more. Yet this waste has to be kept under certain conditions to not overheat. How do you create instructions, signs, a legacy that will ensure the proper treatment of this terrifying waste? Crazy, huh? I feel like this exhibition is my contribution to this priesthood.