The Great Gatsby – Part Bonfire, Part Moulin Rouge 2

Baz Luhrmann’s adaptation of the much-adapted novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald looks a lot like The Bonfire of the Vanities, Brian DePalma’s adaptation of Tom Wolfe’s lurid catalog of the excesses of the 1980’s. It sounds a lot like someone’s idea of Moulin Rouge II.

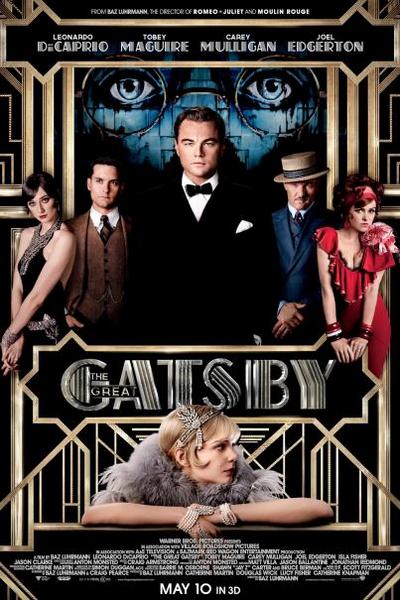

Fitzgerald’s book is narrated by Nick Carraway (Tobey McGuire in the new film), a Fitzgerald-surrogate observer on the sidelines who’s drawn into the boozy mix of new money, old money, and a love lost somewhere in between. Why not? Who wants to sell bonds when you can get dead drunk on bootleg alcohol.

The original book tends toward understatement, even as the bachannals run hot and long. This new screen version which just opened the Cannes Film Festival (in pouring rain) is a raucous melodrama, although Luhrmann leaves room for quiet moments of moral judgment.

Never underestimate the envy that Americans have for the rich, especially for rich people who look like movie stars – Leonardo DiCaprio and Carey Mulligan, for example, who play the doomed striver Gatsby and the heiress with the thug of a playboy husband (Joel Edgerton)who can’t decide to act on her love for Gatsby. Fitzgerald was trying to tell us, once again, that plutocrats can be dumb, cruel, and unhappy. Luhrmann is trying to tell us the same thing, but his $100 million production stresses that the rich are often miserable in elegant cars and sexy clothes that you can’t afford. Is the audience still jealous? Absolutely. You can just imagine them looking at the screen and insisting that they would have been able to make all the right choices.

The production designer, Catherine Martin was aiming at rock opera kitsch here – or if she wasn’t aiming for it, she certainly missed with great accuracy — with locations concocted by someone’s computer that looked like props in a McMansion video game, and interiors with wide spiral staircases that reminded me of the World Financial Center – a place where I imagine financiers are committing crimes far worse than anything Gatsby the swindler was guilty of.

That said, DiCaprio has the right look for his character – an appealing politician’s smile – and the blue-blood accent, that is shown to be confected out of nouveau-riche ambition, does sound fake. Should we fault him for being true to the character’s falseness?

Mulligan has the slinkiness of a spoiled flapper and the uncertainty of a girl who’s forced to choose between love and money. She will probably be nominated for the only award that this film deserves.

Back to the broader twilight-of-the-idols dimension to this moral tale. We watch it with Monday morning’s knowledge that the revelers – or most of them – will be brought down by the force majeure of a depression that hurt poor people a lot more than it ever hurt the rich.

The crimes that we see here aren’t committed in the board room. They’re personal, yet what we see doesn’t make you nostalgic for that time, as Gatsby and Daisie and Nick drive through smoking slag mountains in Queens, the filthy foundation of new wealth, on the way to New York, another playground. (Is this the Queens landfill that’s now called Fresh Meadows?)

This isn’t the last judgment – far from it. Yet Baz Luhrmann’s Great Gatsby doesn’t bludgeon you with parallels to today. Gatsby’s estate looks enough like a Las Vegas reproduction to remind you that excess has been industrialized beyond the North Shore of Long Island. A critic in the otherwise-perceptive Guardian thought the story was set in the Hamptons. His mistake shows that the connection to today was made.