Spielberg’s Lincoln Memorial: Decency, by Whatever Means Necessary

The conclusion of Lincoln by Steven Spielberg (USA 2012, 165 minutes) is that Abraham Lincoln is a saint. Why else would Spielberg make a film about a historical figure? That said, this sacrament in devotion to Lincoln is a long earnest lesson about what Spielberg thinks history should teach us: decency, by whatever means necessary.

Much of Lincoln plays like medicine for adults that someone will try to get young people also to take. It’s hard to imagine anyone under 50 going to see this movie on his or her own. But don’t underestimate the educational market for this movie, especially since so few people under 50 read books. (This movie adapts a book by Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln.)

Lincoln takes a manageable slice out of a long unwieldy public life – Lincoln’s sprint, after his re-election in 1964, to get passage of the 13th Amendment, which outlawed slavery. The quandary here, in a movie that operates more on acting mechanics than drama, is that Lincoln’s allies in the congress hoped that the amendment might help end the bloody Civil War – one of the few messy scenes in the film is a bloodbath of hand-to-hand battle that echoes comparable sequences in Saving Private Ryan and War Horse. But the war might end anyway. We see that the Confederates want peace, which would make the amendment irrelevant to most in Congress who have no interest in black equality. Complicated enough?

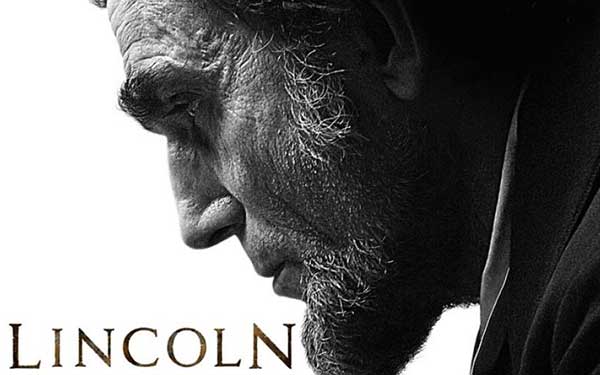

Daniel Day Lewis, as a home-spun sage and fixer, explains things in a sentence or two, and in some long stories that remind you why ponderous political fables aren’t told on late-night television. Part Ben Franklin, part Bill Clinton, in a high voice that is said to have carried over the huge crowds that assembled when he spoke. You expect no less from a prophet.

If you want that kind of verisimilitude of character (in the acting of Sally Field as Mrs. Lincoln, as in Lewis’s Lincoln), this is your film. It makes you want to vote to put him in the White House for another term. But the turgid story makes you wonder whether you want him in office for those long two and a half hours.

If you want that kind of verisimilitude of character (in the acting of Sally Field as Mrs. Lincoln, as in Lewis’s Lincoln), this is your film. It makes you want to vote to put him in the White House for another term. But the turgid story makes you wonder whether you want him in office for those long two and a half hours.

Spielberg intends Lincoln to be a reality check, a portrait of a president who enjoyed the art of politics (cajoling, patronage, even bribery) when it served a greater good. Sound like Bill Clinton?

Visually, the scenes often have a Disney-esque feel of wonderment, as if we’re witnessing history being made, with characters beaming as they announce this or that. Never mind that, with a few exceptions, the production design is as tidy as in any HBO docu-drama – and the film seems edited at the last minute to reach a manageable length, probably mandated by the studio. Political figures pop up during votes, and we never see them again, or learn why they are there in the first place. That’s a lot of makeup for a little exposure.

But Lincoln speaks to us today, the film suggests, not just because you can get a star to play him in a movie. In the Civil War cesspit of political attacks and corruption, much like today, Lincoln was willing to compromise his methods to achieve a noble end, and fast. One person at a screening I attended call Lincoln “Inglorious Basterds” for blacks. Like most things that people say after they see movies, this is an exaggeration, but it points to something worth noting.

In the shadow of this stolid celluloid monument (which Spielberg constructs in his own medium), the recent Republican campaign to keep blacks from voting in the presidential election can be seen for what it is, a racist gambit to prevent a black president from being re-elected. Some lessons bear repeating, even for more than two hours. Don’t expect a bipartisan audience for this film.