Lance Armstrong, in The Armstrong Lie

American Beauty — Three Folk Stories on Film

One great American genre is the tale of “what almost was and what might have been.” In Hollywood they call the glittery place where this happens the Boulevard of Broken Dreams, now living up to its name as a neighborhood where runaways wander amid syringes, steel gates and homeless-proof benches. It’s the tragedy of talent unfulfilled, of promise snuffed out young.

All this is the stuff of film — one of the last places besides the emergency room where losers get equal time.

In the Village

Which brings us to the entertainment business, or to a distant corner of it, exhumed in the new film by Joel and Ethan Coen, Inside Llewyn Davis. A young singer (Oscar Isaac) is broke, without a place to live, performing begrudgingly at folk joints back in the days when an apartment in now-gilded Greenwich Village was dirt cheap. Llewyn (a Welsh allusion to Dylan?) has lots of talent, but the black-bearded singer also has a temper. He’s worn out the patience of his sometime lover (Carey Mulligan) who’s married to a fellow folksinger (Justin Timberlake). He also alienates an academic sociologist at Columbia and his wife (right out of a Weavers’ concert) who could be relied upon for a couch of last resort. We’re on the eve of self-destruction, and this was before folksingers took drugs.

It’s fitting that the look of Inside Llewyn Davis is grey on grey on black. This was when the Village was an Italian neighborhood, with a few Bohemians scattered around. Since only fragments of that unrestored, unpolished Village are left now, we see mostly interiors and an alley or two. The Coens’ reputation for production design remains intact here, especially in the Columbia academics’ apartment. These were the days when people believed in the sociologists who helped resurrect the great figures of folk and blues.

One classic figure who contributed some of the contours of Llewyn Davis was the late Dave Van Ronk, a Village fixture and singer/guitarist who, like the Llewyn character in the film, brought traditional tunes to the young crowd — not a songwriter, just a singer who could fill a room with his heart.

The folk business back then wasn’t cutthroat, but only because the throats out there were not worth cutting. A scene that reveals a lot has Davis going to the office of his manager, Mel Novikoff (later a film legend in San Francisco), who won’t give the kid more than a few bucks. Kinder, gentler days? It would be a while before a few of those singers would be able to make a living with their art.

Another scene, in a recording studio, brings Davis together with pals (Timberlake and Alex Karpovsky) for a novelty song (remember those?) sung in the voice of an astronaut who gets cold feet about being shot into outer space. It’s a reality check, reminding us that if one part of youth culture back then was reverence for the heroes of the almost-forgotten folk and blues, another part was the whacky, irreverent MAD magazine. After all, the farthest that Llewyn and company get to the vast stretches of Woody Guthrie’s West or to the delta of Mississippi John Hurt was a road trip to Chicago with a pompous entertainer (John Goodman) and his monosyllabic pretty-boy assistant. Illusions don’t die hard here; they don’t come to life.

Back to that recording session. The song was Please Mr. Kennedy, a reminder that one’s fate is bound up in larger things — an apt parallel for what this sad, entertaining tale is all about.

On the Road

If the injustice of fate — no matter how good you are — is the thematic rumbling under Inside Llewyn Davis, the tag line “is that all there is?” might be right for Nebraska by Alexander Payne.

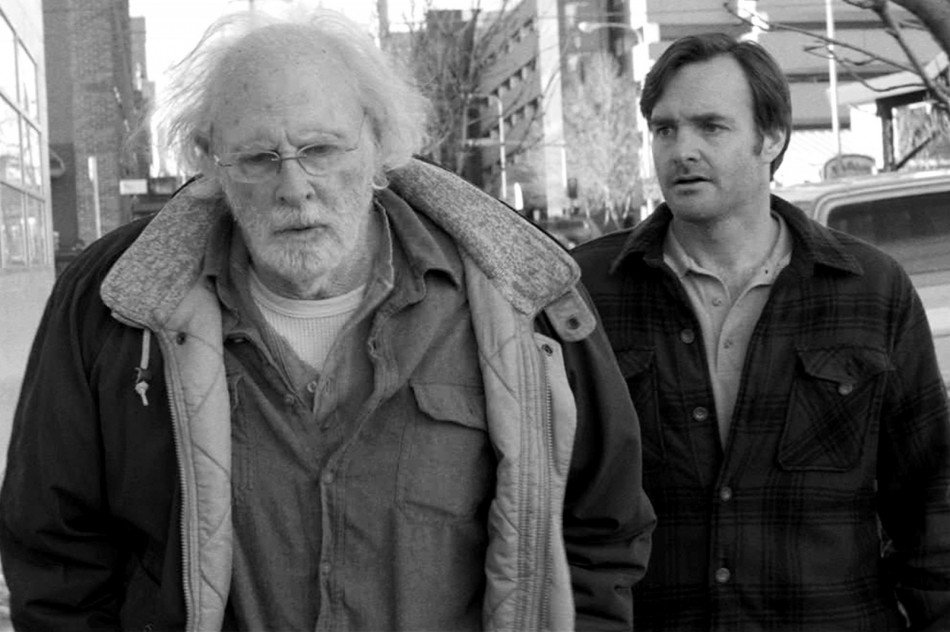

The feeling that “it’s the end of the line” is always with you in this film where people never stop moving. Woody Grant (Bruce Dern) is walking in the wrong direction along the freeway when he’s stopped by a local cop in Billings, Montana. (Is there a right way to walk along the freeway?) He’s heading for Omaha, where he expects to claim a prize from a place that sounds a lot like Publishers Clearing House — even more of a racket than a state lottery.

Thus begins a road trip to toward Omaha, the Jerusalem of this prize-bestowing odyssey, although most of the film unfolds in Hawthorne, the one-street town where Woody was born. The bars are still there, as are the same men with whom Woody grew up. Small-town America isn’t any more evil than anything else, yet it’s still unforgiving, which can look worse than evil, especially when you film it in black and white, and especially when the people who knew you back in your youth learn that you are about to come into a huge amount of money. Woody isn’t the only one who’s ready to believe outrageous stories.

Nebraska was filmed in what looks like late autumn, when the leaves are off the trees, and the landscape that you see from the road has a bare, unadorned flatness. Similarly stripped of everything but his ragged clothes and his belief that fortune owes him something, Woody couldn’t care less about visiting his relatives and old friends, who are ready to pick up life where they left off. With the homing force that families have for frayed emotions, they mock him and his dutiful son, David (Will Forte). So much for the green, green grass of home.

Yet Payne gives us characters here that make it well worth the visit. There’s Woody’s acid-tongued wife, Kate (June Squibb), who can’t find anything but fault in him, and who’s convinced that every man in tiny Hawthorne was out to get her into bed back in the day. It’s as much of a delusion (and even more self-serving) as Woody’s belief that he’s going to walk away with millions — so preposterous that you find yourself thinking that Payne might have met a woman just like her.

Stacey Keach plays a smug small-town businessman, Woody’s former partner, as a local ringleader, a village bully still presiding over the same men at the same bar. Woody’s two nephews, Cole and Noel (Devin Ratray and Kevin Kunkel) — now in their forties and round — are the kind of overgrown children that you find in places that have not evolved.

Part of Nebraska, in its black-and-white aura from another era, points to a backwater that time has left behind. These are towns that are losing population. You can see why. The film makes you look back to the 1970’s, when Dern was a leading man and crackpot journeys were the stuff of movies by Hal Ashby and Bob Rafelson that made wondrous cocktails of comedy and sadness. We’re grateful for Payne’s twist on the ideas of the road movie and a homecoming.

Around the Bend

As road movies go, The Armstrong Lie by Alex Gibney tends toward the literal — bikes racing down the road. The movie has its origins in a myth: the resurrection of Lance Armstrong from a cancer victim into a champion of the Tour de France. Yet there was a problem: Armstrong was taking performance-enhancing drugs, and he was lying about it. A celebrity in Austin and Aspen (as he was everywhere else), the hero was crumbling under scrutiny.

By the time the audience gets to the documentary, Alex Gibney has already shot a film about the improbable and laudable achievements of a man who was given a 50/50 chance to live. The surprise was not that he lived, but that he won the Tour de France.

But it was all a lie. Beware of a documentarian betrayed. Armstrong lied to Gibney while Gibney filmed the original Armstrong doc, and Gibney pursues him, not just to get the record straight, but to have Armstrong provide the correction — a public burning at the stake, with narration from the offender. Armstrong finally tells the truth, but there are two caveats. The first comes from other bikers, who say that they all did it. Sounds a bit like Wall Street. The second comes from Armstrong himself, who states that if he hadn’t doped in order to become a champion, he would not have been in a position to promote cancer awareness in the way that he did.

If lying weren’t enough, bear in mind that the US Postal Service, with our tax money, sponsored Armstrong from 1998 to 2004.

Faced with depositions this November in a case brought by an insurance company to recover bonuses paid to Armstrong for his Tour de France win, Armstrong settled for a cash payment rather than be placed under oath. He paid off his opponents rather than be forced into a position to tell the truth. Saved once again from what could have been a worse fate.

Gibney’s achievement in the film is to show how Armstrong resembles his own sport of cycling. Like sailing, cycling looks graceful, sometimes elegant, from a distance. Up close, in the crosshairs of the camera, we see that it’s a cutthroat war, with cyclists doing whatever they can to get to the finish line first. Usually that involves cutting off other competitors in dangerous ways that can result in injuries that end careers. All for a greater good.

Inside Llewyn Davis

Inside Llewyn Davis

Nebraska