Wright Again

When you are in rainy New York this summer, one of the exhibitions to see is “Frank Lloyd Wright: From Within Outward.” At the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, through August 23. (Taliesen West, Scottsdale, 1937-59.)

Back in the 1930s, when the young Museum of Modern Art had already declared itself the arbiter of all things modern, architecture curator Philip Johnson made a statement about Frank Lloyd Wright that he lived to regret. Johnson called Wright “the greatest architect of the 19th century.” Very clever, yet very wrong. Youll see why at the exhibition, “Frank Lloyd Wright: From Within Outward.”

The Guggenheim salute to Wright (1867-1959), at the house that Wright built, marks the buildings 50th anniversary and a march through Wrights best-known achievements. How could the show be anything else, given the iconic structure where its installed?

As you might expect, the single path through the exhibition ramps upward momentously, culminating with the model of the Guggenheim Museum. If the Guggenheim cant organize a show with the premise that the museum itself was the pinnacle of Wrights oeuvre, who can? The shows curator is none other than Thomas Krens, former director of the Guggenheim Foundation and now an “adviser.”

Even for Wright scholars, theres a lot to savor in the selection of drawings, about a dozen models, and precious few photographs from some 64 projects. There are even obscure forgotten projects to discover.

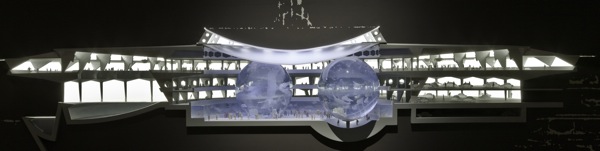

The faded and yellowed architectural drawings are often hard to decipher, yet their unreadability, as if they were by Michelangelo or Piranesi, seems intended to make Wright all the venerable. Whats frustrating from a presentation point of view classicizes his reputation. (Below: Model of Pittsburgh Point Park Civic Center (1947), unbuilt. Model by Kennedy Fabrications. Photo: David Heald.)

Youll be reminded that Wright was a visionary, a prophet from the fields of Wisconsin. Its now conventional wisdom that he gave architecture a horizontality that he took from the prairies. His open plans breathe with freedom as much as any text by Walt Whitman, Henry David Thoreau or any other American transcendentalist.

Wrights Usonian houses, offered at $5000 in the late 1930s, combined egalitarianism with an inspired elegance that made them hard to sell to Depression-era customers who just wanted a roof over their heads.

As with all the greats, Wright made it look easy, and obvious. In his austere and intimate Unity Temple, which had all the hard edges of a rudimentary Protestantism that might as well have been Illinois state religion, Wright elevated the floor on which congregants gathered into a sort of piano nobile, stressing the specialness of gathering. This floor- not an altar – was the real sanctuary. It makes an eloquent statement of humanism in a sacred construction.

The exhibitions thesis is that Wright started with the activity at the core of a buildings interior and worked outward, never simply conceiving a design as a work of sculpture. That notion sounds like an implicit jab at the eye-catching logo-tecture of so many museums these days – odd coming from the Guggenheim, a patron of so much architecture that seems to work from the outside in. Im also not sure that the within-outward thesis explains why Wrights only standing skyscraper (1952-56), is sited in flat and empty Bartlesville, Oklahoma. It was erected after many failed attempts to build storied predecessors like a mile-high tower in Chicago and a church-sponsored tetrahedral spire sited on Second Avenue in Manhattan (1927).

If all roads did indeed lead to the Guggenheim for Wright, one little-known stop on the way was the Gordon Strong Automobile Objective and Planetarium, planned in 1924 for Sugarloaf Mountain in Maryland. As drawn, the building looks like an inverted Guggenheim, an ascending set of concentric volumes that narrow into a dome as they rise. Its mountaintop site in Maryland northwest of Washington, overlooking the Potomac, may explain why the then-futuristic building was never built. Too bad, Washington missed out on a real monument. (It also failed to build Wrights cluster of skyscrapers designed for Crystal City, across the river from Washington, which the architect designed in 1940. So much for second chances.)

Another precursor to the Guggenheim was the unbuilt design for the Pittsburgh Point Civic Center (1947), an aquarium-like structure built around a sphere of water filled with fish.

The model and drawings in the exhibition call to mind Wrights kinship, not with anything from the prairie this time, but with the fantasies of visionaries like Jules Verne. Lyrical and dreamy, the Pittsburgh project looks like something that Jean Nouvel (nothing if not a 21st-century Verne) might fantasize about. Sound far-fetched? Note that Nouvel has designed a museum under a dome with its own micro-climate, on an island now being bulldozed into existence in Abu Dhabi.

And that same dreamy futurism is exactly what Wright achieved with the “Great Workroom” in his Johnson Wax headquarters in Racine, Wisconsin (1936-39). Think of its thin tree-like interior columns as lily pads. The vast room has an underwater serenity, otherworldly enough to be Atlantis. If Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977) could take the mechanized workplace and turn it into a showplace for a Grand Guignol attack on inhumanity in his movie Modern Times, Wright could take an idea that seemed equally preposterous – one enormous harmonious office – and create a serene workspace.

Even more ambitious was Wrights participation in a 1957 plan to remake Baghdad, with an opera house and headquarters for the countrys telephone company. (The master plan included designs by Le Corbusier.) This might make you reconsider whats new about Abu Dhabis recent recognition of the power of architecture, as the country commits billions toward the construction of a cultural district with buildings by Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Jean Nouvel and Tadao Ando. (Perhaps whats new is that the Guggenheims Thomas Krens is involved.)

No surprise, Wrights Baghdad designs couldnt really be called modernist. His opera was something of an orientalist fantasy, a thin tower pointing into the sky like a minaret. St. Exupery couldnt have done it better.

Once again, Wright was ahead of his time, and the project was never built. It conjures up a what if proposition that takes us back pre-Saddam. Could architecture by Wright and company have made a difference in Iraq? Skeptics could understandably note that the buildings would have been prime targets for the Bush-Cheney crowd decades later. Will Halliburton be managing the latest version?

Theres a lot to consider as you walk up and down Wrights ramp in New York, not least the role (or non-role) of the Guggenheim in keeping its own building standing.

Were able to visit a restored museum, thanks to money from former museum trustee Peter Lewis and the City of New York to renovate a structure that had been maintained mostly with coats of paint over the previous decades. The preservation would not have happened without him. Anyone who cares about architecture should be grateful.