Seeing Is Believing: Images for Change

Writing in The New Yorker in October of last year, Malcolm Gladwell queried the influence of social media on social activism and concluded that the superficiality of social networking alliances is not the stuff from which change agents emerge. Or, as Gladwell more succinctly says, “…weak ties seldom lead to high-risk activism.”

Gladwell’s points of comparison are the historic—and Facebook/Twitter-free—events of the 1960s Civil Rights protests in the south; specifically, he references the Greensboro lunch counter sit-ins and the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project, from which three murders and multiple other acts of horrific violence resulted.

But Gladwell’s thesis ignores a key ingredient of social media’s impact on activism. Occupy Wall Street, as a movement, is pervasive and viral, but also visually stimulative. Ranging from raw to finished product, this is a movement of photography, video and symbols.

As anyone who has ever RSVPd to an event with no intention of attending or wished happy birthday to a relative stranger knows, social media interactions are easy and commitment-free. “Liking” Occupy Wall Street’s page is certainly not the same as showing up to a protest and risking arrest and worse. Nor, it turns out, are the two actions mutually exclusive.

Clearly, digital technology has been instrumental toward creating the tipping point for the “Occupy” movement. According to Occupy Together, as of Oct. 8, 998 cities had organized efforts in sympathy with the original New York protest that began Sept. 17. Most of the Occupy groups, if not all, use Facebook as a unifying platform to share related content. Overall, in approximately three weeks time, a relatively small effort has gained international and celebrity attention, as well as a shout-out from President Obama during an Oct. 6 press conference:

Clearly, digital technology has been instrumental toward creating the tipping point for the “Occupy” movement. According to Occupy Together, as of Oct. 8, 998 cities had organized efforts in sympathy with the original New York protest that began Sept. 17. Most of the Occupy groups, if not all, use Facebook as a unifying platform to share related content. Overall, in approximately three weeks time, a relatively small effort has gained international and celebrity attention, as well as a shout-out from President Obama during an Oct. 6 press conference:

“Obviously I’ve heard of it. I’ve seen it on television. I think it expresses the frustrations that the American people feel—that we had the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression, huge collateral damage all throughout the country, all across Main Street, and yet you’re still seeing some of the same folks who acted irresponsibly trying to fight efforts to crack down on abusive practices that got us into this problem in the first place.”

Media coverage of Obama’s speech mostly focused on the president’s recognition of the legitimacy of Americans’ economic frustrations. I found it notable that the president mentioned seeing the protests. Putting aside the medium—television in Obama’s case—the Occupy Wall Street movement underscores the actual power digital tools have for social movements: accelerated iconography.

Gladwell puzzles in his article, “Where activists were once defined by their causes, they are now defined by their tools…Are people who log on to their Facebook page really the best hope for us all?” Again, Gladwell maintains, through the lens of a social scientist, that the weak links that connect users of social media do not provide the requisite resilience for sustained social activism.

His premise, though, ignores the major impact imagery has and can have on individuals—an impact arguably as important as interpersonal relationships in raising and maintaining social consciousness. The value of social media tools for protest in today’s world isn’t to spread information; rather, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and the like allow people to share their documentation of a moment in time, in the moment that it is happening. (Steve Jobs’s death took down Twitter Thursday night.) As a result, Occupy Wall Street is a flash art movement that reflects, as much as any other sentiment, the pervasive distrust the public has for filter. Since the 1970s, distrust of the motives/message taxonomy has only been growing—and with good reason. Protesters chanting “the whole world is watching,” while videotaping acts of police force on protesters is as much a nod to social media as it is to moral negligibility.

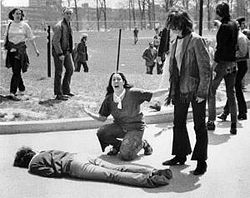

At the root of all political art is the desire to show the world its true face. The root of American idealism is a belief in justice. Underpinning all American social movements is the belief that the first step to justice is the revelation of its absence. When the protests end, usually what remains is the artistic embodiment of the struggle. This is why, when I ask my college students in a Social Movements and Action class to tell me what they think of when considering the anti-Vietnam protest era, one of the first remarks describes John Paul Filo’s Pulitzer-prize winning photograph that captured the 1970 Kent State shootings.

“Fifty years after one of the most extraordinary episodes of social upheaval in American history,” Gladwell writes, “we seem to have forgotten what activism is.” Actually, it would seem, we have only just started to remember.