Photo: Billy Farrell/BFAnyc.com

Report from Aspen: Aspen Art Museum, Design by Shigeru Ban, Opens

Shigeru Ban is this year’s winner of the Pritzker Prize; has an upcoming appearance in Prospect 3, the New Orleans biennial; and on August 9th saw the public opening of his Aspen Art Museum many years in the planning. The coverage of the building got fast-reduced to the snap over tortoises, whom artist Cai Guo-Qiang’s “Moving Ghost Town” exhibit had constrained to carry iPads on their backs in a rooftop exhibit. One thousand PETA signatures and one concerned veterinarian later and the tortoises were evacuated to undisclosed locations.

I got to the Aspen Art Museum the next day with a friend with an injured ankle, the significance of which shall eventually be revealed.

If the turtles’ perambulations were a shuffle heard round national media — what about the museum itself, around $25 million to construct, peppering a salvo of controversy heard round Aspen?

Ban’s oeuvre includes private architectural commissions as well as humanitarian work such as temporary and emergency shelters for refugees. Some of the latter projects have been discrete, to say the least. (For Rwandans displaced by civil war, for example, 50 Ban shelters were constructed for a project of the U.N. High Commission on Refugees, a tiny number compared to the refugee camp populations numbering two million.)

But as is frequently and justifiably stressed, it is the interlocking of many bureaucratic systems that architecture like Ban’s pops up in, incorporating innovative new building systems, local solutions and what the west loves to laud: consumer culture recyclables (like cardboard paper packing tubes that are built details at this museum.) These win him the eco-conscientious moniker. This the architect certainly is.

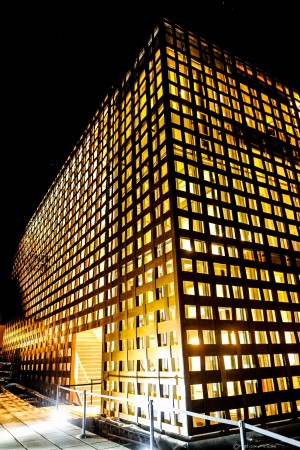

Aspen Art Museum’s new exterior is clad in a motile, lattice-like screen that actually is wooden veneer incorporating resin and paper product. Ban used lattice-work at another art setting, the Pompidou-Metz in Metz, France, where wooden strips formed the roof. Here in Aspen the wood veneer is non-structural. It enlaces the building’s form like stiffly wrapped packing wire or tape. But surface rigidity turns pictorial gesture on the inside where the lattice opens up small frames on the town. Looking south to Aspen mountain from the restaurant on the roof, gondolas shuttle up the emerald green slope; turning back to the art, you take the down staircase back down, with care, as its steep pitch indeed visually echoes the ski slope.

Formally speaking, there are a lot of visual double entendres. There’s the double, tri-level staircase which is divided interior from exterior by a glass wall. As counterpoint to the walnut-colored woven screen, ash-colored timber truss supports the roof. There are echoes between this patterning and some of the whimsy of the roof structure on Ban’s schoolroom for a village in China devastated by earthquake.

The new museum is elegant.

How well it will stand up in the construction detailing? Another matter, maybe. (Regrettably calling to mind that big repairs on Daniel Libeskind’s Hamilton wing of Denver Art Museum began almost as soon as the building opened, here the elevator was out of service just two weeks after the museum had opened. Which led me to get a real-time commentary on the stair detailing from my friend.)

This museum in downtown Aspen has been a hot topic in every sense of the word. That partially stems from the site on Hyman Avenue. Originally the Ban museum design was meant to go on North Mill to the west, in a parklike setting where the former, “old” museum building now lives. When you’re on the roof of the Hyman Avenue building, it is “site-specific,” Ban says. I didn’t quite see that.

Discussing this with an Aspen-ite, she held that the building’s claims to be site-specific fail to mention that it was drawn to be on the first site, North Mill, and not altered when the location did.

Programmatically, the new building at 3000 square meters or about 32,000 square feet triples the old museum’s exhibition space. (I’ll review the David Hammons-Yves Klein show in another post.) In total it confers six galleries; a temporary artist residence; a gift shop as well as the restaurant on the roof.

The question of its relationship to the street remains far more problematic. Some tweens or teens have already used the lattice as a climbing wall. (Wail of sirens.) The impossibility of backing up more than a very short distance on the narrow sidewalk troubles me as it rules out the potential of seeing an unobstructed view of the facade.

Certain design elements (particularly the party roof) evoke David Adjaye’s superlative Museum of Contemporary Art Denver in downtown Denver. But by contrast with that gem-like space, this museum lacks interior intimacy. Heavy doors divide each gallery. Underground seating for hundreds appears anticipated via a bench of almost comic proportions one level below ground. Is the public meant to shelter from tornados?

Dana Goodyear in the New Yorker has written a post stressing the building’s elegance; elegance being a word Ban’s work tends to invite. She also noted Ban as civic ecologist and rich Aspen as in need of ecological consciousness raising. All that may be so, though indeed it’s New York calling the gilded kettle black, and anyone seriously attending to the directions the art world is going might doubt that this commission for contemporary art will goad people to care more about humanitarian architecture. Not bloody likely.

As to Aspen’s own significant year-round intelligentsia of architects and artists and writers, the ayes have it in those most closely attuned to new art or new anything in Aspen. They see the building as connected to a promising program, and a fresh breath of architecture in a town where A-frames to the umpteenth power are the norm, and Penny Pritzker’s own residence designed by Renzo Piano is invisible to the street — all set about by, what else?, Aspen trees.