“Myth of the City” Asks Participants to Create Better Ones

As part of Artfest12 at the Santa Fe University of Art and Design, Gabrielle Guerin and Bruce Matthes are conducting a three-week workshop, Myth of the City. Gabrielle Guerin is Head Architect for Cargo of Dreams, a non-profit organization that partners with rural villages to provide orphanages, clinics, and schools. Author of three books on design and art, Bruce Matthes is the Program Chair of General Education at NewSchool of Architecture and Design where he teaches humanities courses including Literature, Myths & Symbols, and a new class, The Evolution of Surfing.

What does it mean to explore cities in terms of narrative and mythology?

B: It’s an attempt to uncover the experience of a person in a city who is participating in something other than mere commerce.

G: For example, today we went on a “flaneur” walk around downtown Santa Fe. We began in the plaza, in a circle, and each student went out in a different direction – a path of discovery so to speak. “The happy wandering/wondering.”

Myths by nature develop over time. They are often part of an oral tradition and they often have a moral underpinning. How does that translate into a learning experience for students?

B: In the same way that they are created over time, they must also be discovered over time. As we explore the history, literature, art, and culture of a place we begin to uncover its secrets- but the story seems to change with our experience of the artifacts that we examine. For example, each student had a unique story of their city, different from students from the same city, based on experience, lives, interests, etc.

G: This workshop is more about the individual student and less about the actual myths that make up cites. Each student is uncovering what has shaped their understanding, their rituals of life, and their personal beliefs. Our hope is that by starting the conversation – a 3-week conversation – students will become chief questioners, always curious of the “why”.

You began by having the students imagine an apocalypse, draw what that might look like, and then have another student create a narrative from the drawing. The students create connection to each other from the beginning. Ultimately, they will create cities in teams. How does catastrophe lead to imagined cities?

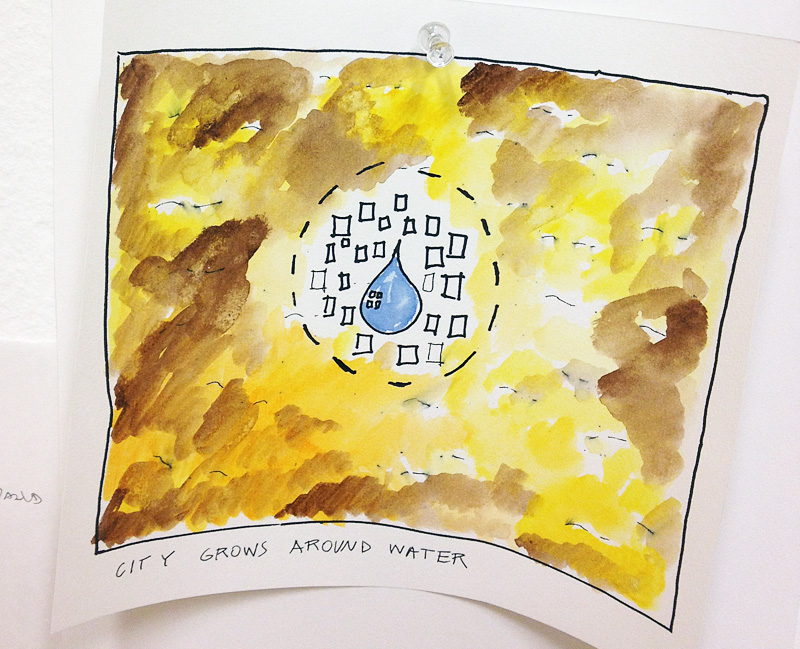

B: The apocalypse scenario was designed to eliminate all of their known experience with place and use their primal instincts to begin to recover the basic necessities of life. The hope was that this exercise might eliminate some infrastructure or ways of living that may not be necessary or are no longer productive or beneficial to the needs of a community. They had to work together to form common goals and define their basic needs to feel that they could survive and that they wanted to continue beyond basic preservation.

G: This idea of “New Beginnings” is to strip the student of their preconceived idea of what a city is. When we ask the basic question, “what is most important in a city” they answer with concrete ideas of what they already know and understanding. How can we begin to teach something more poetic, beautiful, or dare I say utopic, if we remain in the mindset of what we already know? New beginning allows the student a fresh start. Will there be animals? Will there be sin? hierarchy? and beyond.

B: The New Beginnings scenario is mainly to put the students in the environment of understanding what happens to the psyche when something changes the landscape and life so quickly. Haiti comes to mind because I worked on a design charrette with students who wanted to help but they only understood how to make new buildings instead of internalizing the initial concern of the people, not just from a survivor standpoint but also from a psychological one. Then What architecture is needed to help heal – historic preservation or rebuilding? And, how can new architecture prevent another catastrophe?

Are they architecture students, urban planning students, or art students?

B: The workshop was designed to engage a variety of students in different disciplines; however, the 20 students who signed up are architecture students from Chile, Mexico, and Brazil, and they are very serious about how the workshop may help them think as architects. They also seem to have a desire or sense of social responsibility that connects to cities beyond the design of buildings.

Those countries, Brazil particularly, have done some very interesting work in improving slums and underserved communities. In a practical sense, how do you think this workshop and the ideas generated by myth and imagination can be applied to contemporary city planning?

G: One of our students commented that these exercises allow him to think outside of the tangible problems to “how it can be otherwise.” That’s the substance of this discussion. Yes, we know how it is has been, we have seen where the problems lie, but perhaps instead of continuing to investigate these ideas, we can come around from the back and say, “how should it be?”

By considering “what could be” without any constants, restriction, or promoting, we are empowering students to imagine an environment that is more harmonious with their ideals. This of course is often borne of discontent with current situations.

B: I think the expansion of the imagination the imaginable world is the first step to forming new possibilities in the real world.