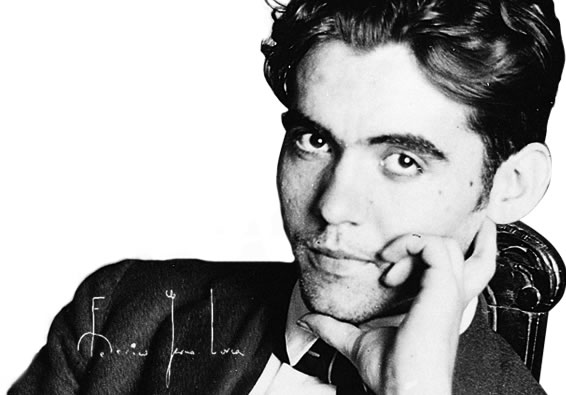

What Lorca Meant to American Poetry

“This is not a book about the Spanish playwright and poet Federico Garcîa Lorca (1898-1936).” So begins Jonathan Mayhew, in the preface of his study Apocryphal Lorca (Chicago, 2009). Instead, Mayhews subject is Lorca’s manifold influence and importance for American poetry, beginning soon after the poets death, but blooming around 1950 and continuing strongly through the 1970s.

Aesthetically, Lorca’s work has stood for a high, sometimes rhetorical expressivity; for a “Spanish” vein of surrealism; and for a primitive authenticity, in his use of folk poetry, his romantic theory of the duende, and his repertory of images from rural life. (Mayhew argues that Lorca’s poetry gives a frame to these “primitive” elements, making sophisticated, erudite use of the larger Spanish tradition. But reading him in translation, and abroad, these complexities have been muted.)

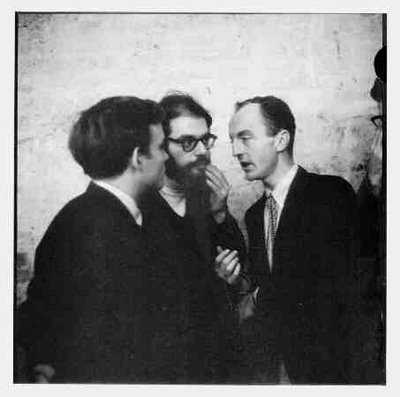

Frank O’Hara talking to Allen Ginsberg

Personally, Lorca’s life has been an example as well. Though not primarily a political poet, he was a genuine martyr of the left, murdered outside Granada by rightist forces on the eve of the Civil War. And he was an “out” gay poet. Uncloseted if not unconflicted, he meant something particular for poets such as Allen Ginsberg, Robert Duncan and Frank OHara. Further, Lorca himself came to America, spending much of 1929 in New York, attending language classes at Columbia and traveling in the Northeast. His poetry of that period, gathered as the collection Poet in New York, addresses America directly, both its present inhabitants and Lorcas chosen forebear Walt Whitman.

The first Lorca translation was a bilingual edition of Poet in New York, in 1941. Criticism of Lorca in English begins in the late 1930s, with a piece by W. C. Williams. By the 1950s, Lorca was well-known, and there were several selected translations to choose from; he began simultaneously to appear as a point of reference in new poetry. Robert Creeley wrote a minor poem “After Lorca”, based on a text someone told him was Lorcas. Frank OHara mentions Lorca at a few points, notably in the short poem “Failures of Spring”; for him, Lorca is less a model for poetry than for a poetic lifestyle, and specifically a gay one. Kenneth Koch made extended use of Lorca and the duende in his poetry teaching and textbooks, and also in his parodic sequence Some South American Poets (1969).

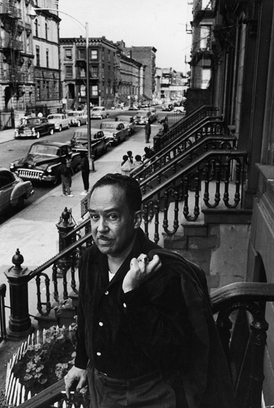

Langston Hughes On The Stoop

Lorca was decisive, though, for Jack Spicer (1925-1965); and for readers unfamiliar with this enigmatic poet, Mayhew’s discussion of the encounter is a good place to start. Spicer might be described as a West Coast complement to Frank O’Hara: both were gay, both engaged in the visual arts, both avant-gardists who wrote in a casual, jokey voice. But where the gregarious OHara projected a charming persona, filling his poems with friends and acquaintances, Spicer (in life a difficult man to know) challenges the reader more deeply, undermining the notions of persona and even poetic voice.

His “After Lorca” is a sequence of translations from Lorca, complicated from the start by bizarre intrusions. The introduction is by Lorca himself from beyond the grave (“Frankly I was quite surprised when Mr. Spicer asked me to write an introduction to this volume.”) Interspersed with the poems are letters from Spicer in response. Spicer said these apocrypha had been dictated to him by the spirit of Lorca (“just a direct connection like on the telephone”), and theres no reason to doubt his sincerity. The translations vary, sometimes following the original closely, sometimes varying minor details, or rewriting sections, and in half a dozen cases corresponding to no original at all. Throughout the book, we indeed feel the distinct presence of Lorca, alongside the equivocal figure of his translator-medium. The heart of the sequence is a vivid rendering of the “Ode for Walt Whitman”, its energy heightened by Spicers infidelities to the original:

New York of mud,

New York of wire fences and death,

What angel do you carry hidden in your cheek?

What perfect voice will tell you the truth about wheat

Or the terrible sleep of your wet-dreamed anemones?

Lorca has also meant a great deal to African-American poets. Mayhew cites LeRoi Jones (aka Amiri Baraka), and Bob Kaufman (a sort of a Beat). But the most impressive example is Langston Hughes (right), who engaged more deeply with Lorca than any of these poets, even Spicer. Hughes translated Blood Wedding, and traveled to Spain soon after Lorcas death, working with poets of Lorcas circle to translate the Romancero Gitano (Gypsy Ballads). This is not only the best version of this book in English, but, Mayhew argues, some of Hughes own best poetry. It was published only once, in 1951 in the Beloit Poetry Journal. Its uncannily alive, without translations usual uncertainties of tone and rhythm – in the eerie prophetic ending:

Oh, city of the gypsies!

As the flames draw near

the Civil Guards ride away

through a tunnel of silence.

Oh, city of the gypsies

Who could see you and not remember you?

May they seek you in my forehead,

a game of the sand and the moon.

Lorca was also the presiding spirit of the so-called Deep Image tendency. This movement, associated with such poets as Robert Bly and James Wright, was prominent into the 1980s. Mayhew is not much interested in this work, seemingly mentioning it for completeness sake; since Im ignorant of it myself, I would have appreciated a taste.

But Deep Image began with a different group, particularly Robert Kelly and Jerome Rothenberg, in the 1960s. Rothenberg has gone on to be a remarkable figure in poetry: the founder of “ethnopoetics”, a hybrid literary/anthropological approach to oral and written texts from many cultures, and an ambitious and influential anthologist. In 1983, when Lorcas Suites were reconstructed from scattered sources, Rothenberg was commissioned to translate them for the Collected Poetry. Invigorated by this return to his early influence, he went on to write a sequence of imitations and original poems,” The Lorca Variations”. Reviewing these, though, Mayhew seems to have hoped for better, finding value mainly in some of the translations.

One strong point of Mayhews book is that it organizes this literary history on a different principle than the familiar personal and aesthetic lineages: Deep Image apart, there is little talk of schools as such (Olson, Pound, Black Mountain). Rather, seeing what each poet made of the “external” influence of Lorca, we meet a range of poetries on their own terms. And another is Mayhews subtle and illuminating argument for how Lorca “worked” as a model for American poets of the Cold War era: through a kind of extended analogy, between the exceptional position of Spain in Europe and the post-war sense of American exceptionalism in the world.