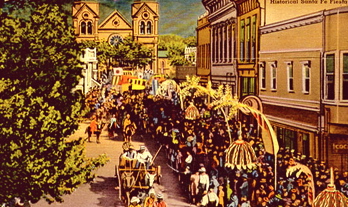

Thoughts on Santa Fe’s Legendary Zozobra, An Historic to Modern Spectacle

He’s been burned and rebuilt since 1926. He hangs from his pole, a large-scale marionette, and watches through bulging eyes as the crowd grows larger and the fireworks burn brighter. He’s seen families eat picnics at his feet, children point at his curly hair, artists circle his skirts, and teenagers throw him a finger. He himself changes year to year — eyes grow narrower, lips fatter, ears rounder. The ritual of his doom incurs his fury and for one night Santa Fe listens to him moan. The fire dancer taunts, the lights scare and the shouts keep his arms flailing and head twisting in an uproar until finally he alights with a consuming flame until nothing is left but ash.

Thursday, September 6th 2012, initiated Santa Fe’s annual Fiestas with the traditional burning in Fort Marcy Park of the 50-foot puppet named Zozobra or Old Man Gloom. The month-long celebration of fiestas, culminated this weekend, begins with a blaze of the city’s sorrows, citations, maybe even divorce papers inside of the stuffing of Zozobra. “Que viva la fiesta!” the Santa Fe Fiesta Counsel shouts in their grand entrance to the event. “Let the celebrations begin!”

Old Man Gloom did not always exist as part of Santa Fe’s September Fiestas. Like the city, it grew as an event by its unusual creativity. Fiestas began in memory of the Spanish re-conquest of New Mexican territory after the Pueblo Indians successfully chased them out in 1680. In honor of the re-conquest, leaders organized parades which included a portrayal of the Conquering Conquistador, Don Diego de Vargas followed by a portrayal of a Pueblo leader. This was not such a cheerful a sight if you were part of the losing side. Things were added, like the Fiesta Queen and her princesas, an Indian princess and the supporting counsel, but around 1950 an artist and veteran of WWI called the celebration “dull and commercialized” and he did something about it. His name was Will Shuster.

For years the parades, dances, songs and catholic masses were a trade mark of the Santa Fe Fiestas, but as the city grew in artistry and diversity more and more visitors felt a bleakness that couldn’t be swept away by parading the counsel through town. Shuster came up with the idea of Zozobra when he saw a a burning figure of Judas being carried through the streets of Mexico. Representing evil, the Judas figure was adapted to the image of a monster which Shuster burned with a group of friends in his backyard. The idea was that Shuster could burn away his “great pre-fiesta worry” and give a better show for the occasion. The ritual caught on. Zozobra, which means Gloomy One, was moved to a parking lot then to the elevated field of Fort Marcy Park in the 40s. At first, the construction of the puppet included a simple white gown beneath an enormous head and it was mostly done by Shuster’s group of friends. The fire dancer was added to the ritual as an added taunt, New York ballet dancer Jacques Cartier made use of a tall streaming hat and large miming movements to antagonize the moaning monster until his ignition. The burning methods remained experimental until Zozobra was officially handed over to the the Kiwanis Club in 1964, at which time Harold Gans perfected the construction with wood and carefully placed pyrotechnics.

Shuster was fascinated by Santa Fe’s younger generation and their reactions to Zozobra. When asked why he continued the annual burn, the Albuquerque Journal quoted him as saying, for “the look in the youngster’s faces as they [see] this monster who might have stepped out of a fairy tale go up in smoke.” The fantastic features of the beast was said to revive the inner child.

As a child, I colored my own Zozobra with my classmates and we hung them on the walls of our elementary school. Our glooms were written on pieces of paper and we were told they would be added to Zozobra’s robes, where they could burn away. I wrote something like making new friends and keeping good grades, a typical fourth grader’s wish, but admittedly I wrote the same wishes every year. The fiesta counsel joined our school assemblies, parading in pairs with the music, “Si Señor, como no, vamonos al vacilon…” repeating over and over. We would clap and cheer, then Don Diego and La Reina would introduce themselves with the rest of the Fiesta Counsel, telling us how exciting the next month would be. Afterwards we all got up and danced to the Mariachi music. We took the bait and went home begging our parents to see Zozobra. Ten years ago, my family and I would arrive at Fort Marcy early to eat, dance, and talk with friends. The lights and Fire Dancers would begin after sundown. It was scary for a while, the monstrous groans and the whipping arms, but when the time came I shouted along with my mom, dad and brother, excited by the energy.

When asked the impact of Zozobra in this decade, many of us respond, community. The admission charge has benefited Santa Fe youth in scholarships and programs while volunteers and local entertainment contribute their time and talents in preparation and pre-show. That’s what Zozobra is, one grand show! For whom exactly? Zozobra has always attracted young crowds, from the high schools and the colleges, but most importantly it has united the three cultures of Santa Fe: Hispanic, Native American and Anglo. For one night their interactions serve as a reminder of Santa Fe’s history and growth. Though the Fiestas surround a Catholic counsel (just as an

evil Judas goes to the Christian story), the pagan Zozobra, immolated as voices rise in unison to “Burn him!” also has bearing in many straw men or effigies of pre-Christian cultures.

For better or worse, Zozobra – a field of gloom set to go up in smoke – now gets filled with people ready for party standing shoulder-to-shoulder beneath large view screens, to the blaring music and the fearsome grimace of the puppet himself. The rave-like atmosphere cannot be stopped. The monster ignited at 10:30pm this year, and as the fireworks flared for Zozbra’s final breath, and the crowds streamed out, the spectacle remained just as cathartic as it has ever been.