Sherrie Levine and the Critics

Roberta Smith writing in The New York Times Friday about Sherrie Levine: “Mayhem”, at New York’s Whitney Museum through January 29, inquired whether the show, like an “art boutique full of fastidious, expensive-looking objects lightly dusted with irony” meant that a mistake had been made: “I’d like to think that Ms. Levine is a better artist than this, but I’m not sure.”

You won’t find this particular review on Whitney dot org’s list of press coverage. But this New York Times take-down bears on the powerful Smith powerfully missing the point. Smith, who used “taunting” to describe Levine’s acts of emergence – well-chronicled outright appropriations, such as rephotographing Walker Evans and being chased by Getty curators and lawsuits – is right that Levine has always been a provocateur. 1981, the “Untitled: After Walker Evans” open date for “Mayhem”, was some three years after Levine was admitted to Douglas Crimp’s 1977 show at Artists Space, “Pictures,” which also included Richard Prince, Cindy Sherman and Robert Longo.

There is in Levine’s meticulous body of work a 30-year tango both with the viewer (or the appropriator) “finishing” the object; and with the relationship between fetish, non-object, murderous rivalry, and finally, flaunting identifications, that are all part of what Levine does and has done. Hence, for Smith to suggest that Levine as a sculptor is “just awful,” woke me up in the night, reflecting on how Smith’s spartanism interfered, in this review, with clearsight.

In cases that I personally experienced, Levine as a sculptor stopped me proverbially dead.

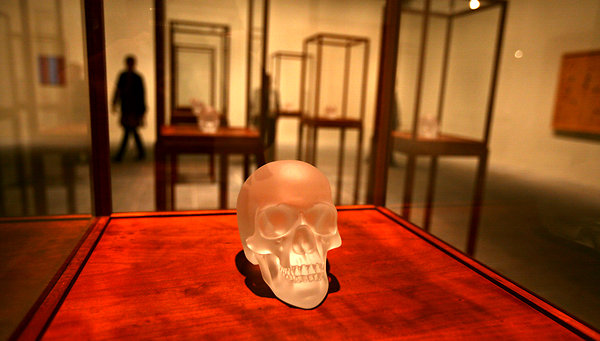

Smith particularly objects to Levine’s sculptures, after Brancusi, named “Newborn,” which are cast glass – crystal or black – and which indeed have in common with the seminal sculpture by Constantin Brancusi that in a bronze object managed to assimilate, like Bird in Space, everything that was new, shiny, aspiring yet unattainable about the 20th-century (perfection?). Newborn’s opacity to interpretation even as it were in the process of being experienced, also applies to Levine’s crystal glass forms that could be said lightly to also incorporate the position of the African tribal masks of Man Ray.

In 2005, the Menil Collection in Houston mounted an installation of “Black Newborns,” for which Levine placed crystal newborn heads atop grand pianos. Not lolling about as if just set down randomly, but arranged precisely centimeters from the brass fittings that mark the line of the piano lid, the better to hear you with my dear. In 1989, at Mary Boone Gallery, “Crystal Bachelors,” castings from the bachelors of Duchamp’s Large Glass, each occupied a vitrine in the gallery. Levine as a sculptor has cast, fabricated, tried out finishes, changed up and rethought appropriation and mimicry with a consistency that has won her this moment in New York’s fall art season.

Nothing “light” about the “Newborn” irony at all, the delicate symbol of a head, embryonic emergence, fragile glass. Set atop the apotheosis of cultivation: the concert piano shone to indelible gloss.

Sherrie Levine, "Newborn," collection Los Angeles County Museum of Art

You can’t understand Levine without gloss. And without the irony of a pun that may play out entirely in her own head and never be revealed materially. It’s what can make the work obtuse, infuriating, a study in refusal. Levine’s gift of mimicry is unsurpassed. But she releases the first finish from its relationship with the mark eternal in the instant of her willful and pushy over-identification with source.

So much for “museum-gift-shop fare,” about which Smith complained in describing Levine’s Newborn as “the semi-abstract head of a wailing infant, which she renders in cast glass and cast crystal.” P.s. Roberta, it’s not “wailing,” and neither Levine nor the piano would care if it were.