Robert Frank at Metropolitan Museum of Art

Last Saturday Robert Franks film Cocksucker Blues (CSB) (1972) played at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where a 50th anniversary exhibition of Franks The Americans runs through January 3.

Frank looked at ordinary Americans, and at the unkept promises of the land of plenty in The Americans, his last work in still photography before abandoning the medium for moving pictures. In CSB, he peered behind the scenes while traveling with the most glamorous rock band of the time – the Rolling Stones US tour of 1972, timed with the release of Exile on Main Street. With Frank, the work of art usually involves a journey. CSB was Franks look at celebrity and at what was then the ultimate victory lap.

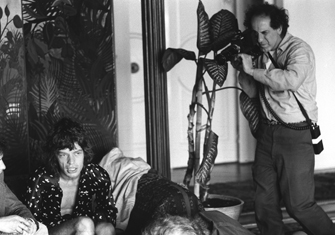

Ken Regan, Mick Jagger and Robert Frank at Michael Butler’s House in L.A., 1972. Courtesy of Ken Regan/Camera 5

No surprise, sex, drugs and rock n roll werent all that they were cracked up to be (no pun intended, since this was long before the crack era), but the Stones and their entourage experimented with everything just to make sure.

Glam comes in brief spurts in Cocksucker Blues. Boredom, however, is a big part of the mix as Frank observes the group in hotel rooms, in backstage locker rooms, and in their flying harem of an airplane.

Its a legendary notorious film. At times you feel it might be more subversive in its undermining of the celebrity glow than Jagger and co. were in reaching hands under the skirt of propriety. Rebels only to a point, the Rolling Stones certainly felt that way. They or their management didnt want the band seen shooting up or beating drums in a primitive ritual at 30,000 feet, in which women were stripped. Someone warned them that to keep selling, the Rolling Stones couldnt go completely over the top. The Stones did not want to be Roman Polanski. (Below: Super 8 footage of the Stones shot by Frank in 71 before Exile On Main Street.)

CSB, which belongs to the Stones, can only be screened once a year, at a museum or non-profit organization, and only if Robert Frank is present. Hence the screening at the Met. Hence the minimal exposure for the film most of the time, although its easy enough to get in degraded versions on the Internet.

The Stones began as fans of Robert Frank. Pictures from The Americans are on the cover of Exile on Main Street, which looks like a contact sheet from the beatnik days. The Stones loved that. They didnt love Franks insistence on showing them how they looked. Yet sometimes it takes an outsider to help see whats close to home. Alexis de Tocqueville did it for a new nation in Democracy in America in 1835, and we still read that book today to learn about ourselves. Robert Franks somber testimony in The Americans also still haunts us, 50 years after publication in 1959.

Frank came to the US at 23 after World War II, a Jew from wealthy Swiss family, and his view of America has much of the frontier in it. Landscape in American painting and photography had been elegant and monumental. Franks landscapes, eerie enough to be a blank slate for a David Lynch film. were empty and silent. Sometimes a single car travels through them, transporting settlers in a still-unsettled place. Franks peer and pal, Jack Kerouac, made an adventure of the lonely highways. Yet for Frank the heartland seemed mournful. (Kerouac recognized it, though; he wrote the introduction to The Americans.)

If the automobile had already conquered the landscape in Franks lens, the weak grey light of television, a presence in the pictures, was promising to be Americas new hearth.

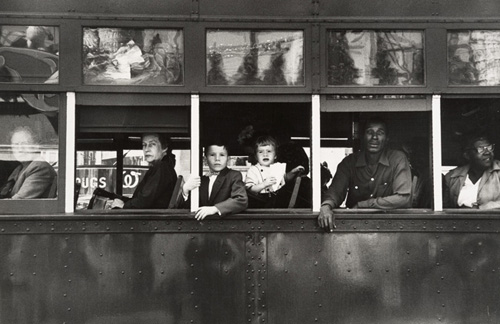

The city photographs that Frank took were sober alternatives to the happy snapshot. They were unsettling glimpses of people who were either solitary or found themselves alone together in streetcars and diners or on sidewalks. One cross-section – Canal Street New Orleans – had quirkiness of a Norman Rockwell group portrait of puzzle pieces that dont fit, minus the warm humor.

The Americans was never a celebration of America. Yet, while the grim Frank might not want to see it as such, it celebrated photographys refinement as a medium. For education, Frank took some cues from French photographers of an earlier generation, who found a special true lyricism of place in the public life of its ordinary citizens. Using an approach pioneered by Walker Evans, for whom he worked as an assistant, Frank observed the improvised American bricolage of street signs and advertising that sprang up like weeds wherever people gathered – and stayed after they moved on.

But Franks drive-by portraits were all his own, depicting not only people, but the distinctive objects around them, not just Americans, but America. Photographers have drawn from his work ever since, trying to out-Frank him by wringing sentimentality out of their pictures, but Frank led the way, and then deserted them for film. No nostalgia emanates from Franks black and white photographs.

Either theyre still too contemporary in mood (another inspiration to photographers today), or they show us sad pages of our own history that we are pleased to have turned.

Frank himself turned the page, abandoning still photography after The Americans for filmmaking, which became more and more personal as the years went on. Yet those pictures remain icons. Like monuments, these icons are likely to outlast all of us. And like the best monuments, we keep returning to them.