Quilting for their Lives: Pakistani Women at Santa Fe International Folk Art Market

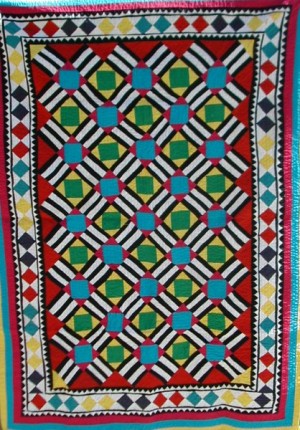

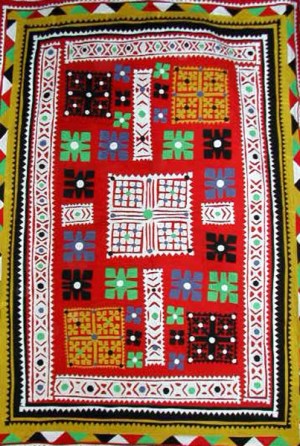

In a remote village in the Thar desert of Pakistan, the women are primarily Hindu in a Muslim country. Not only that, but they are from the bottom of the untouchable caste system. They have very few options in life for what they can do to earn a living. Most of the women are illiterate and are forbidden to travel without their husbands or a male relative. The men dye cotton and the women take that cotton and stitch together brightly patterned Ralli quilts. They embroider, appliqué, and adorn their creations with bits of mirror, sequins, shells and beads. The patterns are based on ancient textile traditions dating back thousands of years.

“Portuguese traders in the 1500s brought back boatloads of quilts to Europe. Those quilts were described as being brightly colored with lots of bordering,” Patricia Stoddard said via telephone from her home in Utah. She is the author of the book Ralli Quilts: Traditional Textiles from Pakistan and India – and has been the agent of the Ralli quiltmakers, Lila Handicrafts, whose quilts she first took to the Santa Fe International Folk Art Market in 2004 to give international exposure to the women working in stark poverty to create these beautiful objects. They’ve participated in the Market, occurring July 8-10 this year at Museum Hill in Santa Fe, every year since.

Stoddard serendipitously came upon Ralli quilts while living in Pakistan. Her husband was a Defense Department attaché in Islamabad. They were provided a big, empty house and she was looking for items to decorate the enormous white walls, something colorful. She spent hours in handicraft shops looking through stacks of textiles, embroidery, weaving; at the very bottom of the stack she found a quilt. Having lived on the East Coast, Stoddard thought the quilt reminded her of Amish quilts, but made with very intense color. The shopkeeper told her it was a quilt made in the villages, but that nobody was interested in buying them, so he didn’t carry many in his shop. In a different store she found another quilt appliquéd with sequins. Then she found some in the museum, and was told , “they make them in the villages.” Stoddard estimates that 25 million people sleep under these quilts every night. They are made for home use, given as gifts on the occasion of marriages and births. The more quilts a family owns, the wealthier they are considered. Often the quilts are made and exchanged as currency for a buffalo, cow or goat to provide a permanent milk source for a family.

“I am totally in awe of the women that make these quilts. It teaches me that if women of the West, we have certain skill sets, we learn certain things. They have memory for pattern and I have never seen a written description. Somebody had one on a camel that went by. They grew up in a village and this was the pattern. Most of the intricate patchwork patterns have no mistakes. There’s an integrity to them. They have no cutting boards, no tables, no quilt frames, no rotary cutters. It’s a needle and thread and fabric that they make these out of. It’s just amazing,” Stoddard said.

Stoddard helped launch Lila Handicrafts when she was contacted by a son whose mother made quilts and was looking for a way to sell them. He managed to get a digital camera and send her images. She sent money to them via a Western Union account and they shipped her the quilts. Their appearance at Santa Fe International Folk Art Market in 2004 was a boon for the quilters. The sale of the quilts has provided money for the cooperative to develop local schools, including the new Santa Fe Desert School, named in honor of the relationship the women have with the Folk Art Market.

“It gives me such a feeling of connection with these women because the things that they think are beautiful I think are beautiful. I can appreciate the hours of work it takes, in some quilts the stitches are completely hidden and the appliqué looks like it is magically adhered to the background. There is a connection. A great similarity to what we perceive as beautiful and fine work.” Stoddard said.

This year, the Lila Handicrafts Ralli quilters will also be featured in an exhibit called “The Arts of Survival: Folk Expression in the Face of Natural Disaster” opening July 3 at the Museum of International Folk Art, curated by Suzanne Seriff, a folklorist from the University of Texas, Austin.

The exhibit is about natural disaster and “the way folk artists garner every means available to them to survive and help other people in their community survive,” Seriff said. She had the genesis of an idea and about the same time last summer that the Clinton Global Initiative was meeting in Santa Fe to discuss Haitian disaster relief following the earthquake, there was also this huge flood in Pakistan. So Seriff narrowed down her exhibition to the four elements: earth, wind, water, fire and selected one disaster from the 21st Century for each of those primal elements gone awry: The earthquake in Haiti, hurricane Katrina, the flooding in Pakistan, and the volcanic eruption near Java, Indonesia.

In Pakistan, the region most hard hit was the Sindh province, where Ralli quilts are prominent. “I started looking at the pictures on the news services and they showed people with bundles on their heads of these colorful quilts. They were ubiquitous,” Seriff said. “I heard reports of women in the relief camps who had been there for months and were running out of food and supplies, no money, no identification, using any scraps of materials they could find, materials cut from clothing and blankets sent from around the world, to create the quilt tops. They were selling them to relief agents and neighboring markets to survive. Many of the women had brought with them, their dowry pieces, quilts that had been made for them or that they had made for their daughters. They were willing to sell them to get money to go home.” The exhibit will feature two dowry quilts made by different women.

And, for the first time ever, Surendar Valasai, husband of a quilter, will travel to Santa Fe for the International Folk Art Market and Art of Survival exhibition t MOIFA. Because he agreed to come, his wife, quilter Naina Valasai will also travel from Pakistan to the United States. Surendar travels back and forth to Karachi to mail quilts. He speaks English – and Seriff has asked him to share his experience of working with the quilters in the refugee camps. It will be the first time he or his wife have ever left their homeland.

“I am totally in awe of the women that make these quilts. It teaches me that if women of the West, we have certain skill sets, we learn certain things. They have memory for pattern and I have never seen a written description. Somebody had one on a camel that went by. They grew up in a village and this was the pattern. Most of the intricate patchwork patterns have no mistakes. There’s an integrity to them.

This for sharing this article. Ralli quilts are really wonderful traditional textiles made by the folk artisans of Pakistan.

Trackbacks for this post