Persistently Abstract, New Mexico Artists Paint Now

Abstract Expressionism is America’s great homegrown art movement. British critic Briony Fer reminded in covering Inventing Abstraction: 1910-1925, MoMa’s 2013 reprise of founder Alfred Barr’s first abstract show, that “few episodes in the history of art attract so many origin myths as the history of abstraction.” New Mexico owns its abstraction origin myths, too, from the Taos Moderns through 20th-century “transcendentalists,” to Richard Diebenkorn in Albuquerque on the GI Bill, to Black Mountain College master Jorge Fick. The list goes on.

Abstract painting persists strongly today in New Mexico. The dialogues are more hermetic, more studio-centered, less public than even a decade ago. Its practitioners may resist being labeled as abstract expressionists, as if aware that that term is too limiting for a contemporary painter now. But what gets discussed in front of the paintings evokes the rhetoric that made abstract expressionism the signature, heroic American art movement–and so new.

My degree in visual culture from Goldsmiths College, London (2005), burnished my postmodern proclivities. Goldsmiths bred YBA superstar Damien Hirst. He’s the art-world pop star, alongside Jeff Koons and Paul McCarthy, who saturates international headlines and dominates markets. Their work is the anti-emotional antithesis of abstraction’s personal satin sheets.

When Tate Britain this November opens its new show, Painting Now, five contemporary painters with curator-discerned “distinctive approaches” to new painting take the limelight.

But, previews the Guardian’s Jonathan Jones, “It’s a doubtful proposition that any good painting has ever been made with an eye exclusively on the present.”

In Santa Fe, I wanted to investigate this tension: How do four contemporary abstract painters root in tradition and assert their pertinence through paint?

Shelley Horton-Trippe (b. 1951) – The Now and The Sublime

A sign on a clock in Shelley Horton-Trippe’s south-side studio reads, “THE TIME IS NOW.” She writes in her artist statement, “By bringing the paint and myself back to the ‘now’ I sometimes find that that great philosophical problem I want to solve in my painting has just been accomplished by following the paint.”

The desire to solve great philosophical problems on canvas goes to Barnett Newman’s 1948 manifesto, “The Sublime is Now.” He wanted “real and concrete revelation” without nostalgia for legends and myths. He wrote, “Instead of making cathedrals out of Christ, man, or ‘life,’ we are making it out of ourselves, out of our own feelings.” Artist as “first man” and stripes relating to the Kabbalah made his work as mystical as the concept of “the zip” and “onement.”

But what needed a manifesto in 1948 today sounds nostalgic, even utterly idealistic, although with this caveat: That from the standpoint of a generation that worships technology, maybe the manifestos are still viable.

Horton-Trippe’s painting, Carbon (2008), is big enough to walk into at 6’ x 5’. The canvas is black and rough, textured by broad brushstrokes and sand. A small oil derrick floats in thin, bright white lines and bursts with red-and-orange oil fire. Horton-Trippe is from Oklahoma, and Carbon — more representational than many paintings of hers that reveal a calligraphic, gestural vocabulary– addresses our reliance on fossil fuels.

So here’s abstraction (or expressionism) as a political response, while newer work such as Antarctica or Arctic Circle reveals an environmental concern through their titles, but force the viewer back to their form by way of gestural mark-making as a “signature of emotion” (artist’s statement).

A political stamp adds pertinence but Horton-Trippe’s appeal to something “exalted” still feels problematic in part because of its use of “emotiveness” as a corollary between matter and spirit.

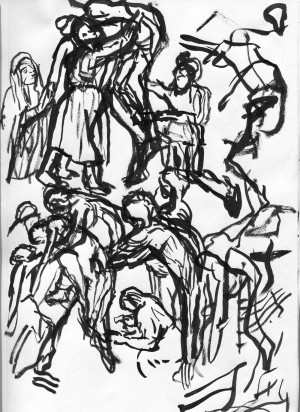

Eugene Newmann (b. 1936) – Gesture and Excavation

From his studio in Ribera, New Mexico, Eugene Newmann grapples with the figure — “the body heading towards death.” He told the Santa Fean in 2009 that “abstract art though secular has aspirations in common with the sacred art of the past.” Newmann is inspired by Goya’s Depositions of Christ, has said he is interested in the human body in poses from uprightness to limpness. As a formal matter, he’s looked widely at entombments and depositions, from Caravaggio to Rubens to Matthias Grünewald. He also looks to the body in yogic poses.

The Bodies (oil on canvas, 34” x 42”) shows two muted burnt-red figures that sag and hunch over on all fours as if devolving through a black hole. Their stubbed hands and feet slip into the ground of pink brushstrokes. A third green figure in the foreground looks into the painting like an ominous Grinch. The geometric shapes delineated on the surface— blue triangles and a black box— possess an architectonics that alienates further the swabby gestural forms of the falling figures.

“A painting,” he says, “is a membrane with the artist on one side and the viewer on the other: what people want to see is what’s on the other side.”

If he’s invoking the mythology of abstraction, who or what is the presence on the other side? An invisible wizard beyond the paint? Man or medium?

Both Newmann and Horton-Trippe are serious painters who emphasize how emotional their personal investment is. If a painting will make a “true believer,” is the price of conversion dropping irony for earnestness?

David Solomon (b. 1976) – Technique and “Transfers”

David Solomon’s painting would fall into the category of a “distinctive approach,” because of his shift in 2010 from painting on canvas to painting on aluminum panel, a slick, non-absorptive surface.

Under Wave, at 36-x-30 inches, outlines a seedpod with clean yellow lines. This blimp floats in the center, on top of a waterfall of drippy violets and reds. With copious amounts of oil medium applied by brush the paint has nowhere to go but down.

As a biotic, sci-fi space, Under Wave hosts a landscape of natural gas vapors ready to generate new life. But Solomon resists describing the shapes as fertile. He says his painting is about “transfers of information.” Indeed, the material aluminum surface references built environments and information highways.

So this has nothing to do with the exalted, or does it?

Solomon, asked about the “sublime,” says he defines that as “honesty” – an answer that might suggest the younger-generation abstract painter is also smitten with metaphysics, just as a new abstract religion where the social virtue is authenticity.

Leslie Ayers (b. 1975) – The Future of Painting?

Leslie Ayers admits that she is “totally in love with the romance and gravity of being a painter” but insists, “these can’t be about me” — meaning, she doesn’t download feelings onto canvas. Her pursuit, she says, lies in the “future of painting.”

Ayers’s gestural marks are disparate and tangled, like graffiti tagging. Your Gold Male (36-x-30 inches) is composed of six black bars applied as slightly bulging brush strokes that stripe the canvas, separated by negative space. The red triangular scaffolding in the top left corner anchors the ground of khaki-colored wash. For Ayers, the verticality evokes the standing human—a conceptual torque that I buy, despite no evident representation of the figure.

Your Gold Male looks urban, gritty even. The image evokes a new city, while the title suggests something cold and hard. When you mix the title and the content, you picture a fallen deity or a street anti-hero, of the kind maybe found in Breaking Bad. Your Gold Male and a couple other of her paintings were styled into the episode, “Madrigal” (season 5).

Painting Now

Abstract Expressionism persists. It’s maybe a bad title for new work that both demands to be taken out of context and can’t be taken out of context, because what Barnett Newman wrote in 1948 isn’t true anymore:

“The image we produce is the self-evident one of revelation, real and concrete, that can be understood by anyone who will look at it without the nostalgic glasses of history.”

It’s impossible to look at abstract expressionist art without those glasses, because the once-revolutionary style is now classical.

Appeals to the exalted and the authentic continue. Painters love to paint. But whether or not emotion can really bridge paint and spirit, or if our virtual personas can even pause on a new definition of “authentic,” is an open question for painting now. It seems inevitable that the glasses of history fog nostalgic.