Writer Sarah Boxer compares Annie Leibovitz's photograph of Emily Dickinson's dress to "branding," in that the closeness of seeing is analog to close-wearing. At Pilgrimage, at Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

On Georgia O’Keeffe, Annie Leibovitz, and the Calculated Cliche

Our age has a “my sister-my daughter” relationship with celebrity. Is it our twin or our spawn?

An interesting question deals not in the obvious worshipful condition, but in how to define a role – and a difference – for art objects in an image- and celebrity-inebriated society like ours. Walter Benjamin wrote the famous Mechanical Reproduction essay back in 1928, but even a seer like him couldn’t forsee Steve Jobs and the sateen of “retina” iPad display.

When I first lived in Santa Fe, two decades ago, objects of art generated the periodic excellent critical essay comparing artists’ oeuvres with their analogy in pop culture. For example, Rebecca Solnit writing on Georgia O’Keeffe and nature calendars in the excellent (now-defunct) art magazine Artissues. In the 1990s for seven years, MaLin Wilson-Powell and I split weeks of writing an art-critical column in the Albuquerque Journal North. Wilson-Powell wrote memorably on O’Keeffe reproduction postcards and the rift between paintings with skies and bones, and pretty picture postcards.

The negative-space doorway of Georgia O’Keeffe’s house in Abiquiu, by Annie Leibovitz, in Pilgrimage.

In New Mexico, of course, Georgia O’Keeffe’s work is the poster child for that over-used adjective, iconic. As the relic where hagiography and commerce meet, the correspondence between O’Keeffe and “place,” is an ecological, aesthetic thing. Come on a “pilgrimage” to O’Keeffe country. It’s a tourism message, underlying.

Annie Leibovitz, magazine cover photographer, did so herself. Admitted as a “pilgrim” to the O’Keeffe destination shrine, the house in Abiquiu, she revivified the portrait of the Abiquiu house — the famous black door (negative space) in the wall that O’Keeffe painted — in photography. Of course in getting to bring a camera in, she was permitted privileges that mortal pilgrims are not. Whether or not the ensuing picture is immortal, it’s having the inevitable appearance in the O’Keeffe Museum — and well, that’s show business.

Along with the Abiquiu black-door picture, square closeups of boxes of pastels, overviews of Spiral Jetty, panels of dimpled New England wallpaper, and other people-less pictures that Leibovitz made, have opened at the O’Keeffe Museum (Feb. 15-May 5). They first were published in a Random House book titled Pilgrimage, which also names the show here in its fourth museum stop, after opening in January 2012 at the Smithsonian Museum of American Art in Washington, DC.

As biography is integral to the O’Keeffe story (see my 2009 post on Saatchi Online Magazine here), we know from Leibovitz biography that she made this work after the death of her lover, Susan Sontag, and after her own personal bankruptcy. Pilgrimage, was a project she and Sontag had apparently meant to do together. For Leibovitz, the two firsts of the journeys were abandoning film for a digital camera, and shooting portraits of places or things without people in them.

It’s hardly new to report that she made visits to Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Concord and to Emily Dickinson’s Amherst, as well as to the aforementioned black door. The pictures are indeed tableaux, and they’re pretty and even intimate – wide, plain, strict sometimes. I have seen them reproduced in media large and small, salon-style and more aired out, and I remain entirely unconvinced whether, despite their museum appearances, they’re art. They’re fine enough pictures, of lore that belongs to the cultural set of being an American and appreciating literary and art history.

What really goes wrong for me is a sense that this show reflects eternal recurrence of the same for the O’Keeffe Museum. For of all the things wrong with the O’Keeffe legend as it’s continually packaged in Santa Fe, possibly the wrongest lies in the fact that the only connections her handlers permit are sanctioned connections. Somebody as famous and celebrity as Annie Leibovitz, sanctioned in. Nothing truly accidental ever occurs that would actually turn the relationship of historic past to contemporary present interesting, because it can’t. Ring up the inevitable quotes about sanctity of “place.” The prohibitions on picture-taking or recording with microphones or saints forbid, touching anything.

To not ring the praises of O’Keeffe to the highest, and to live in Santa Fe, is to be insufficiently pious and subject to chastisement. And the correctness has only gotten worse.

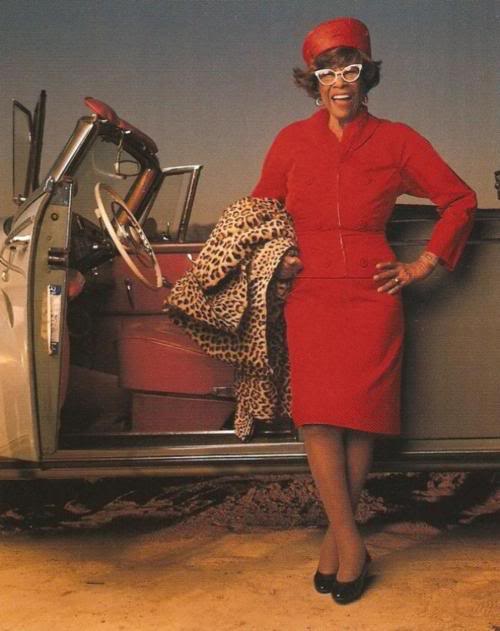

Annie Leibovitz shot Ella Fitzgerald for American Express in September 1986

At the end of the day, after all the Annie Leibovitz-opening-in-Santa-Fe hype surged and subsided on Facebook, with the usual suspects posting their pictures standing next to her, I looked back to watch the Leibovitz interview video on the NewsHour last February. I googled the Demi Moore cover from Vanity Fair (slideshow on Huffington Post) and remembered how when I was coming up in NY media, the client or venue didn’t matter: whether it was Ella Fitzgerald styled for an AmEx ad, or Michael Jackson styled for the cover of Vanity Fair, Annie Leibovitz’s images made commerce and culture interchangeable. They sold us cultural membership in the basic agreement that celebrity is the most important thing of all.

Being a much bigger fan of Emily Dickinson than I ever was of Georgia O’Keeffe, I am happier to think of her in the words of self-description that she used than in the flat and broad portrait of her dress that a New Yorker critic compared to “branding,” as you’d brand a cow. (Emily Dickinson wrote, “My hair is brown – like the wren. And my eyes – like the sherry in the glass that the guest leaves.”)

Ultimately, it’s uninteresting to me that celebrity photographer Annie Leibovitz had a spiritual catharsis in Abiquiu or in Amherst. But if all the hoopla amounts to wanting to rub the lantern in hopes the genie will come out, I can’t help but wonder who’s doing the rubbing — and who’s the genie? Is it Annie Leibovitz burnishing her own reputation as purported heir to O’Keeffe? Or is it Annie Leibovitz as revival preacher for the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, with her appearance pre-approved straight down to the door in the wall just as the maestra herself had seen it? What might the artist herself have had to say about the practice of Leibovitz’s simple-minded postmodernism, in pilgrim’s clothing?