Nazi-Looted Klimt Brings $40 Million at Sotheby’s Auction

A Klimt landscape that that hadn’t been since the late 1930’s by the man whose family owned it before the Nazi Era sold for $40 million last Wednesday night at Sotheby’s in New York.

The sale affirmed a truth of today’s art market, that pictures seized during the Nazi Era which are restituted to their owners and brought “fresh” to auction can bring huge prices when they’re put up for sale. Another truth is that most heirs who recover paintings can’t afford to keep them. It’s good news for the auction houses. The $40 million was some 20% of Sotheby’s evening sale on November 2.

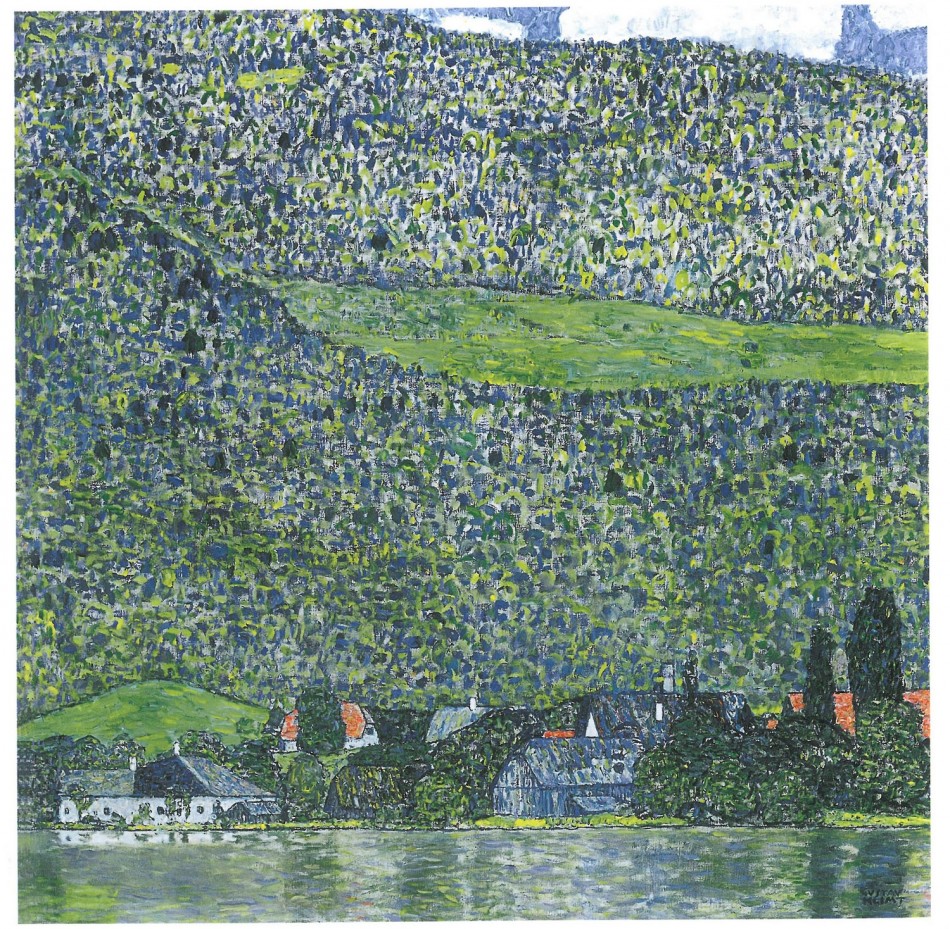

The picture in this case was Klimt’s Litzlberg am Attersee, a landscape of a hillside that rises from a picturesque lake in Austria. Klimt painted it in 1914, the year that the continent went to war, following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the presumed successor to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Some 25 years later, before Austria welcomed its annexation by Nazi Germany in March 1938, the picture (and many others) belonged to the Zuckerkandl family of Vienna, Jews who operated a sanitorium in Purkersdorf, on the outskirts of the city. The building, where the Zuckerkandls lived was seized by the Gestapo in 1938. A storage firm was bribed to house the art and furniture. Most of the family fled. Those who stayed – including Amalie Zuckerkandl, whose portrait was painted by Klimt – were deported by the Nazis and exterminated.

Georges Jorisch Watched the Sale of a Painting Returned to His Family After 70 Years

One of those who escaped was Amalie Zuckerkandl’s grandson, Georges Jorisch, now 83, who consigned the Klimt that sold on November 2. At the time, Jorisch was 10. He and his father left for the Netherlands, where they had arranged to be taken out of the country by boat. When the two arrived at the meeting point for that trip, the boat’s captain had already been intercepted and arrested. Father and son fled to Belgium, where they tried to be inconspicuous. They ended up hiding out for more than two years.

If you read German, look at Thomas Trenkler’s feature about the Zuckerkandl heirs in Der Standard, the Vienna daily. Trenkler has been a constant observer of restitution battles in Austria, and is a reliable source on this ongoing process.

After the Sotheby’s sale, when most of the press corps had left, Georges Jorisch descended from the room overlooking the sale floor where he had watched the sale. The picture had ben purchased by a Zurich dealer, David Lachenmann, who gave no information about where it might be going.

To call the slight stooped Jorisch a man of few words is an understatement. When asked how he felt about recovering the painting that had been stolen from his family, he said, “good.”

Speaking German to an Austrian television reporter who asked what he thought about the sale which brought the second-highest price for a Klimt landscape at auction, Jorisch called it “a life’s achievement.”

It wasn’t an easy process. Jorisch and his father returned to Vienna after the war, to find the city emptied of Jews and emptied of the life that his family knew before the Nazi time. Jorisch’s father was thwarted in his efforts to get any property back.

Jorisch left the country, first for France, and then for Canada, where he settled in 1957 with his wife in Montreal. Son of a lawyer, Georges was never educated past high school. The man whose boyhood home was visited by Einstein, Franz Werfel, Max Reinhardt and Stefan Zweig Jorisch worked in factories for much of his life, and spent his last working years managing a camera shop. Jorisch would eventually recover some of his family’s art, but the lost opportunity for a formal education was just that – lost. He intends to apply the money from selling paintings to educating the younger generations of his family.

In 2000, after Austria had agreed to accelerate the restitution process of looted paintings that were found in state collections, Jorisch was encouraged enough to search again for his family’s property. “The resistance to handing anything back had thawed somewhat,” he recalled. He learned that one landscape had burned in 1945. Almost a decade later, he found one of the pictures in the hands of a private collector in Graz. Church in Cassone, a Klimt painting from 1913 set on the shores of Lake Garda in Italy, sold at Sotheby’s last January for $43 million, setting a world record for a Klimt landscape.

Litzlberg am Attersee, which sold on November 2, was in the Museum der Moderne in Salzburg. It got to the Landesmuseum in Salzburg, and then to e previous incarnation of the Museum der Moderne, called the Rupertinum, as part of a trade in 1944 with the dealer Friederich Welz, who was known for his Nazi Era aryanization of one particular gallery, Galerie Wurthle in Vienna. (Wels, a member of the Nazi Party, is also the dealer who seized Portrait of Wally, by Egon Schiele, which was the private property of the gallery’s owner, Lea Bondi Jaray. The 1912 painting of Schiele’s mistress ended up in the collection of Rudolf Leopold, and later in the Leopold Museum in Vienna. It was on loan to the Museum of Modern Art in 1997 when members of Lea Bondi’s family saw it on the walls, and asked MoMA to hold it in New York in order for its provenance could be checked. MoMA’s refusal triggered a grand jury sub poena by the District Attorney of the New York, and a 13-year battle in Federal Court. In the summer of 2010, after Leopold’s death, the Leopold Foundation agreed to pay $19 million to the Bondi heirs. Wally is now back on the walls of the Leopold Museum in Vienna.)

Georges Jorisch attended the sale at Sotheby’s in New York. Plain-spoken, he said he had no place to hang the painting, nor did he have it insured, and he hoped that the painting would be in good hands with its new owner. He noted that his daughter had a copy of “Church in Cassone” on her wall, and expected a copy of Litzlberg am Attersee to hang in the home of his son. The Litzlberg reminded him of his childhood, he said, noting that the “new generation” of Austrians today were “different people” than the countrymen who cheered Hitler back in 1938.

Georges Jorisch Takes a Parting Look at the Family Heirloom

Different, also, was the attitude of the Museum der Moderne in Salzburg, which returned the painting, said Jorisch, who noted, “they have been very nice.” Litzlberg am Attersee was the most popular painting for the museum’s visitors, said the director of the Museum der Moderne, Toni Stooss, who attended the sale. Stooss, who is Swiss, stressed that there was no opposition within the museum or in Salzburg to returning the work, although Jorisch had been rebuffed in 2002 by an earlier administration at the museum’s previous incarnation, called the Rupertinum. (Restitution experts note that the bad publicity that could come from resisting handing back the picture to Jorisch might not help the marketing goals of a town that depends on foreign tourism.)

In recognition of the museum’s cooperation, Jorisch is donating some $2 million to an expansion at the Museum der Moderne in Salzburg, The addition will be named for his grandmother, Amalie Zuckerkandl, who did in Auschwitz.