The Farm - Home and Harmony in Catalunya

Miró in (Almost) Full — at The National Gallery of Art

Joan Miró was not Picasso. That’s the bad news. The good news was that he was Joan Miró. The more of Miró’s work that you see, the more you will appreciate that.

Miro’s Universe – Sometimes Playful, Sometimes Sinister – from the Constellations Series

You’ll see a lot of Joan Miró in the Exhibition, Joan Miró: The Ladder of Escape, which is at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC through August 12. If you are near Washington, don’t miss this show.

Images begin with the land. Miró would be a Catalan patriot for his entire life, rooted in the region on the Mediterranean below France and around Barcelona with its own language and culture – which the Spanish fascist regime made illegal from the late 1930’s until the death of Francisco Franco. The persecution of Catalunya (also written as Catalonia) helps explain Miró’s despair about Spain, which he shared with Picasso.

Picasso would not return to Spain while Francisco Franco ruled. The artist died in France in 1973. Franco died in 1975. His mausoleum is a vast monument.

Miró returned to Spain from France after World War II began, first settling in Catalunya on the farm that he painted in his famous picture from 1921-2. He later spent much of his time in internal exile in Mallorca, where he lived quietly for the rest of his life – an escape from politics?

The Face of Catalunya

Years before the Spanish Civil War turned Spain into a violent stage for a rehearsal for World War II, Miró painted The Farm (1921-2). Created with affection, it depicts the house where he lived and worked, surrounded by tended plots, a picture of harmony and self-sufficiency, but also of whimsy. Did he intend a allegory of an independent Catalunya? (Ernest Hemingway bought The Farm in 1925 for some $200. The family of the author, who observed the agony of The Spanish Civil War in A Farewell to Arms, donated The Farm to the National Gallery.)

In the 1930’s, as surrealism took hold in Europe, the US and Latin America (as fascism also did), Miró’s images tended toward distortions of figures that seem to be influenced by a fellow Catalan, Salvador Dali. Dali’s figures melted onto the canvas. Miró’s were saturated with colors of the desert.

Dali peddled anti-clericalism in images that still looked sacramental. Miró seemed to be painting paganism. Boundaries of all kinds dissolved. Humans became indistinguishable from animals, and the horizon disappeared in his landscapes.

In Miro’s Surrealism, Boundaries Disappear

Abstraction seemed to be where Miró was heading, or was it just infinity? Soon, in the early 1940’s, Miró would compose his Constellation series. The pictures looked like starscapes composed from what he saw through a telescope. On closer observation, each was a wondrous delicate look into the heavens of his imagination. It’s tempting to say that Miró’s astral patterns that surged their way to the frame were leading the way to Jackson Pollock. Not really. If he has a fellow traveler here in these meticulously composed universes, it is Paul Klee, another master of detail and whimsy. This isn’t dripping, but celestial precision.

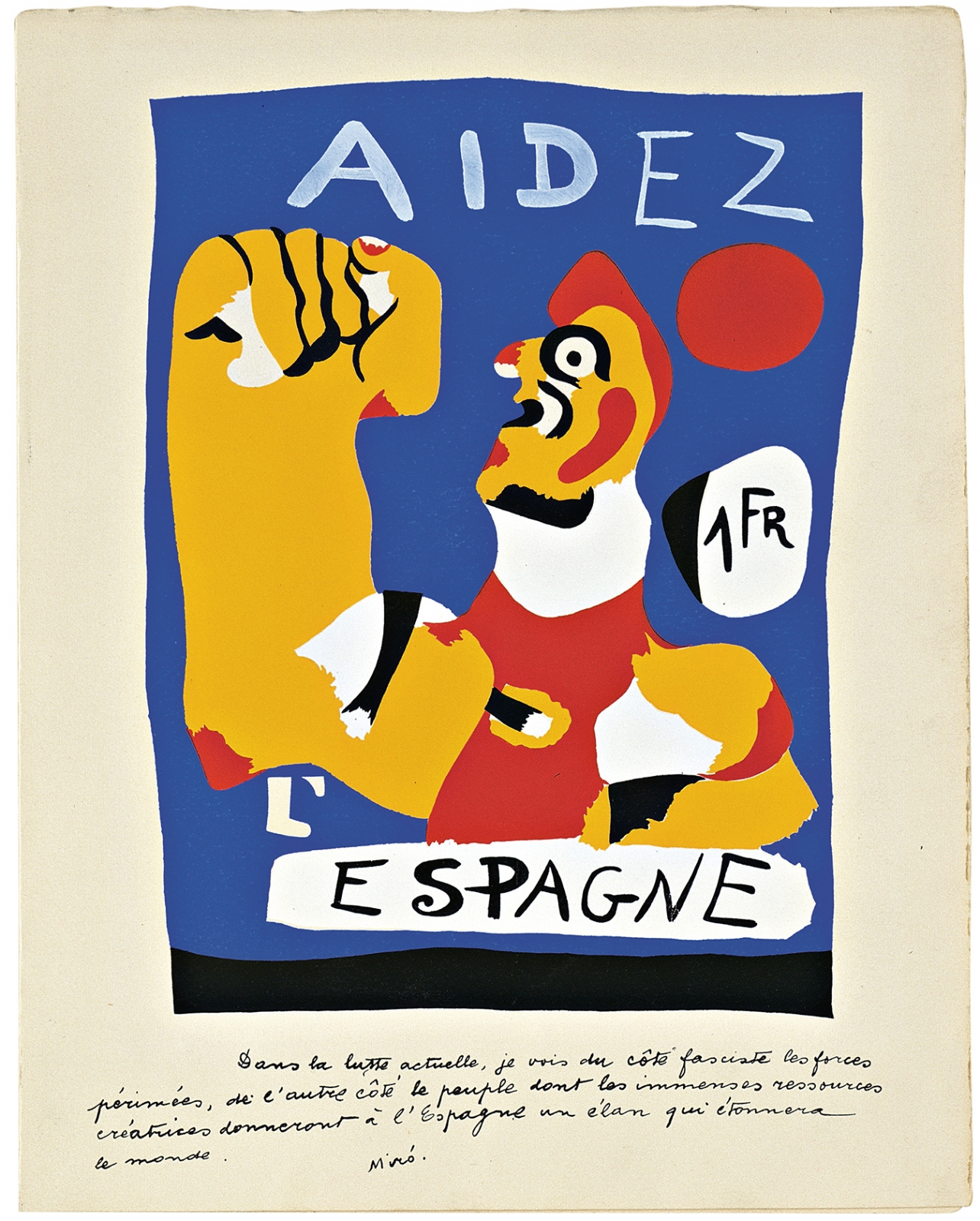

Poltics – Art by Other Means

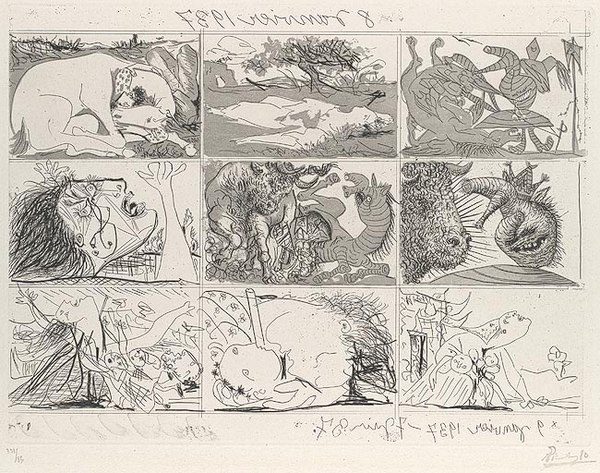

There was a darker side to Miró. After the Spanish Civil War, which ended in 1939 with the surrender of Barcelona, his birthplace, he made chilling drawings on plain white paper, the Barcelona Series. Fifty sheets show cartoonish figures in scenes that blend grotesquery, incredulity and despair. They aren’t Guernica, Picasso’s screaming vision of a village destroyed by bombs dropped from Nazi planes. They evoke a child’s hand, as if that child were remembering different version of a recurrent nightmare, with the some hulking ogres appearing again and again. The pictures were banned in Spain until 1975. The entire Barcelona Series is on view at the National Gallery, reason enough to visit the exhibition. (For Picasso’s version of grotesque satire and mockery of Generalissimo Franco, take a look at his Lie and Dream of Franco from 1939.

The Lie and Dream of Franco – Picasso Does His Cartoon Version of the Spanish Dictatorship

Miró’s profile rose after Franco’s death (1975), when the Fundacio Miró celebrated him, eventually building a huge museum in his honor on a hill overlooking Barcelona. It wasn’t a moment too soon. In the early 1970’s, Miró was deliberately damaging his own work, as testimony to the treatment of critics of the Franco regime.

In the 1970’s, Miro Was Tearing Apart His Own Work in Support of Catalan Autonomy

The National Gallery’s retrospective is the museum’s own homage to Catalunya, celebrated downstairs in the West Building with a Catalan menu. It is one of the best food bargains in Washington. Try it after your visit to the exhibition. Be forewarned — The Barcelona Series is best seen on an empty stomach.

But meanwhile …….

Back in Catalunya, down the hill from Mont-Roig, a short drive south of Barcelona, is the farm that Miró painted in the 1920’s – shuttered and mostly abandoned when I saw it on a recent visit, except for some vehicles and fields where parsley seemed to be growing. The structure, still intact, is owned by Miró descendants, who haven’t seemed to agree on a price to transfer it to an institution that could preserve the site and enable Miró’s army of admirers to visit. The world has grown around that once-isolated patch. A highway almost brushes the back walls – not the safest place for animals to wander.

Somehow, given today’s Spanish economy, it’s hard to see funds to preserve that essential Miro monument being a priority. Money didn’t get in the way of building a Titanic monument to Franco. Let’s hope the farm is still standing by the time the economy rises again. In the meantime, The Farm can be seen at the National Gallery of Art.