Men of God, Men of Nature Makes Denver Art Museum A Mecca

The Fuse Box Gallery on level four of the Denver Art Museum’s Hamilton Building is all angles with slanted walls and sloping ceiling, as designed by architect Daniel Libeskind. A walk-through installation conceived by artist Laleh Mehran interacts with Libeskind’s angles by placing a large, black, acrylic cube near the far end of the long, tilted space.

Mehran’s installation is attentive to the most sacred site in Islam–the  The walk of the pilgrimage has a physical analogue with “Men of God, Men of Nature,” the title of Mehran’s installation and exhibition. Visitors must walk into the narrow entry of the Fuse Box Gallery and around the cube to enter the space, which can hold about ten people. The exterior of the cube is etched with Triangulated Irregular Network (TIN) vector topography, suggestive of a map of the Middle East.

The walk of the pilgrimage has a physical analogue with “Men of God, Men of Nature,” the title of Mehran’s installation and exhibition. Visitors must walk into the narrow entry of the Fuse Box Gallery and around the cube to enter the space, which can hold about ten people. The exterior of the cube is etched with Triangulated Irregular Network (TIN) vector topography, suggestive of a map of the Middle East.

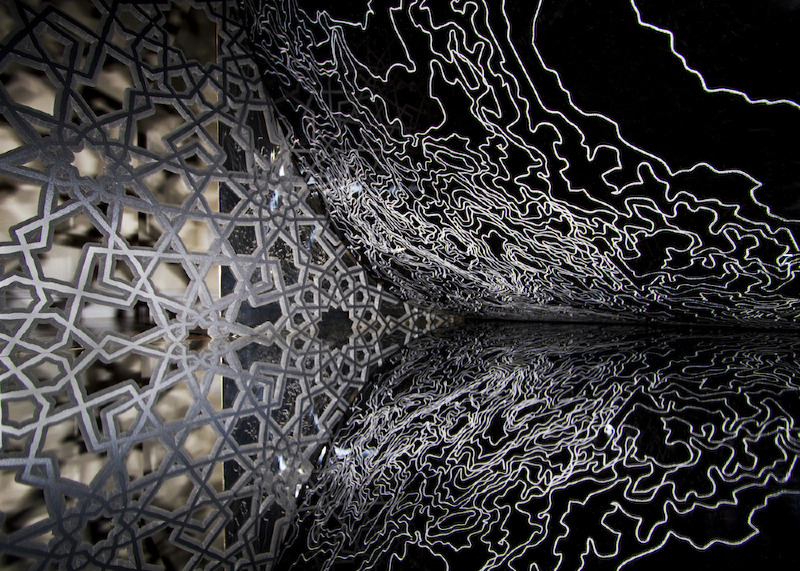

Inside the cube a self-referential component of elaborate calligraphic patterns cut with a Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machine veil partial images of the viewer reflected back at herself. (The pattern is cut into black acrylic, which is layered over mirrored acrylic.) Based on the Islamic arabesque, a geometric pattern that typically portrays repeating floral or vegetal designs often symbolic of the infinite nature of deity, Mehran’s arabesque begins with a pattern centered round a twelve-pointed star. The pattern mathematically disintegrates asymmetrically and the eye begins to wander until the viewer can no longer find the central star but begins to see other lines and shapes forming.

Inside the cube a self-referential component of elaborate calligraphic patterns cut with a Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machine veil partial images of the viewer reflected back at herself. (The pattern is cut into black acrylic, which is layered over mirrored acrylic.) Based on the Islamic arabesque, a geometric pattern that typically portrays repeating floral or vegetal designs often symbolic of the infinite nature of deity, Mehran’s arabesque begins with a pattern centered round a twelve-pointed star. The pattern mathematically disintegrates asymmetrically and the eye begins to wander until the viewer can no longer find the central star but begins to see other lines and shapes forming.

When the viewer steps up into the cube, nine computer monitors surround her. Computer-designed, organic pod-like shapes are triggered by the motion of human presence and appear to come toward the viewer within the monitors. The sensation is one of overwhelm, the elaborate patterns engulfing ambulating shapes, swarming sounds and shuffling movement.

When the viewer steps up into the cube, nine computer monitors surround her. Computer-designed, organic pod-like shapes are triggered by the motion of human presence and appear to come toward the viewer within the monitors. The sensation is one of overwhelm, the elaborate patterns engulfing ambulating shapes, swarming sounds and shuffling movement.

A relationship between transparency and veil interests the artist. “I love how you don’t get to see the full image of yourself,” Mehran says acknowledging that one’s reflection is divided by the arabesque pattern. She wants viewers to question the deep, ideological things that make us who we are. Not only individually, but to also consider that the patterns and the cube shape reflect thousands of years of culture refracting, changing and morphing. Mehran herself is Persian, the daughter of Iranian scientists , and has lived most of her life in the United States. She is a woman turning a representation of a sacred Islamist space into a reflective space for Western visitors. Her questions for the viewer is are you men of God or men of nature? Is it science or is it religion? Is it mathematical or is it spiritual? Nature is referenced on the external surface of the cube through the topographical map. The geography remains the same, but the countries change over time, borders shift and are merely drawn on a map. The interior of the cube could then represent God, with its arabesque patterns, though Mehran’s arabesque is intentionally imperfect, echoing the notion that only God is perfect. The Kaaba is a representation of heaven on earth and was built by Men of God—Abraham and Ismael.

A relationship between transparency and veil interests the artist. “I love how you don’t get to see the full image of yourself,” Mehran says acknowledging that one’s reflection is divided by the arabesque pattern. She wants viewers to question the deep, ideological things that make us who we are. Not only individually, but to also consider that the patterns and the cube shape reflect thousands of years of culture refracting, changing and morphing. Mehran herself is Persian, the daughter of Iranian scientists , and has lived most of her life in the United States. She is a woman turning a representation of a sacred Islamist space into a reflective space for Western visitors. Her questions for the viewer is are you men of God or men of nature? Is it science or is it religion? Is it mathematical or is it spiritual? Nature is referenced on the external surface of the cube through the topographical map. The geography remains the same, but the countries change over time, borders shift and are merely drawn on a map. The interior of the cube could then represent God, with its arabesque patterns, though Mehran’s arabesque is intentionally imperfect, echoing the notion that only God is perfect. The Kaaba is a representation of heaven on earth and was built by Men of God—Abraham and Ismael.

As complex as “Men of God, Men of Nature” appears to the viewer symbolically, its fabrication was even far more complicated and ingenious. Mehran and her husband Chris Coleman built a Do-It-Yourself CNC milling machine in their Denver garage.

As complex as “Men of God, Men of Nature” appears to the viewer symbolically, its fabrication was even far more complicated and ingenious. Mehran and her husband Chris Coleman built a Do-It-Yourself CNC milling machine in their Denver garage.

“Men of God, Men of Nature” will be on display through February 17, 2013. It’s a work that demands to be added to the permanent collection of the Denver Art Museum. It was made to interact with the angles of the Fuse Box space. The experience of the work won’t be the same in any other white cube art museum or gallery. But more importantly, an artist who elevates the dialogue of contemporary art to span the complex patterns of science, politics and religion and the interconnectedness of cultures, countries and creative concepts made the complex installation work in Denver.

“Men of God, Men of Nature” will be on display through February 17, 2013. It’s a work that demands to be added to the permanent collection of the Denver Art Museum. It was made to interact with the angles of the Fuse Box space. The experience of the work won’t be the same in any other white cube art museum or gallery. But more importantly, an artist who elevates the dialogue of contemporary art to span the complex patterns of science, politics and religion and the interconnectedness of cultures, countries and creative concepts made the complex installation work in Denver.