John Sonsini at James Kelly Contemporary: Review

In Santa Fe day laborers congregate near the Guadalupe Chapel at the north end of town. In Los Angeles, where painter John Sonsini lives and works, day laborer immigrants constitute a body of portrait subjects who look out from their canvases with unflinching expressions: sadness or reserve, an unsmiling mien, done with what New York Times critic Ken Johnson has called “Whitmanesque” affection, by the artist.

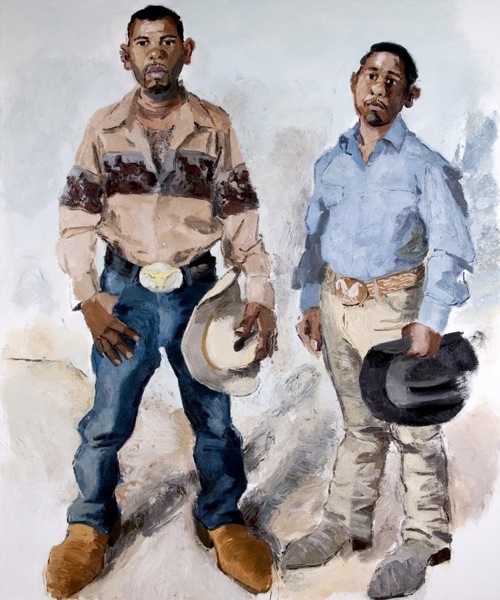

John Sonsini, Roger and Francisco, 2011

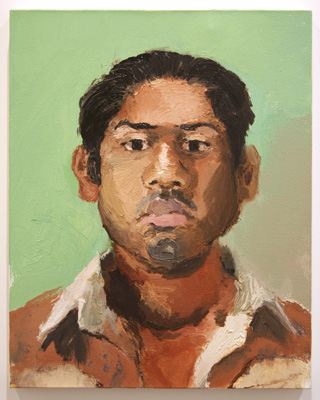

If it’s Whitmanesque, though, John Sonsini sings the body in limbo. His sitters wear their fancy belt buckles and sometimes, dress shirts. They are shod in cowboy boots (and the outsize scale of their feet causes you, the viewer, to regard the portrait from feet to head.) They hold hats in hand; or, like Manuel, a rail of a man with angular cheekbones, have carefully placed the cowboy hat on the floor. Christian’s wide-eyed expression, right thumb tucked into jeans pocket, has a forebearing air (Christian, 2011). Two valises suggest he is just leaving, or possibly has just arrived. The painter has swabbed a pink background behind him, a gentle seamless. Where Ken Johnson sees Whitman, I could not help but think of painter Alice Neel’s pathos, whose portraits of friends, lovers and art-world figures also often captured world-weariness, albeit of quite different variety. Eight new 2010 portraits shown last summer at ACME in L.A. were praised by David Pagel in the L.A. Times.

Now, nine Sonsini portraits on view at James Kelly Contemporary indeed describe that identity is mutable, the degree to which we “see” others about a requirement to look for the detail in the eyes, in the faces of men whose eyes we might more typically avoid.