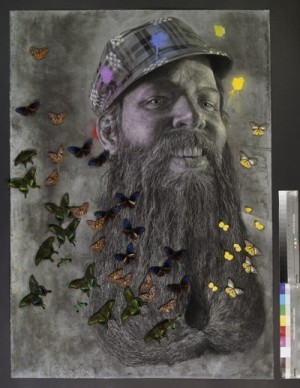

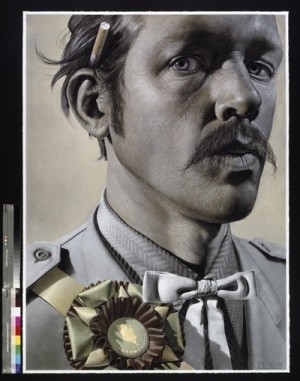

Ian Ingram (American, b. 1974), "The Wedding Quilt", 2008. Charcoal, pastel, beeswax and beads on paper, 60 x 44 inches (152.4 x 111.8 cm)

Ian Ingram Mapmaker-Draftsman

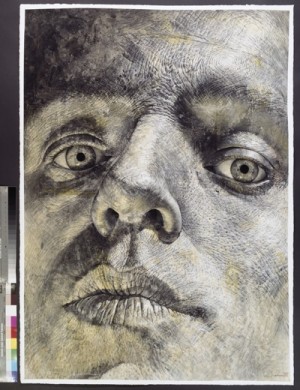

Ian Ingram works standing with a large magnifying glass on his left attached to a retractable stand and placed opposite a mirror. On his right is the sheet of paper on an easel. Both are illuminated. He works slowly, examining his reflection through the magnifier and transferring to paper what he sees with the objective facility of a dedicated cartographer. A single drawing takes two to three months to complete. While Ingram is not opposed in principle to using photographs to help him see more, he finds that in practice, visual curiosity is constantly engaged in the mirror, and more often than not is shut down by looking at a photograph. Ingram believes that working from photographs feels like copying the work of the camera. He explains, “If I can manage to engage my eyes enough to draw from photos, I end up with a drawing of a photograph, not a drawing of the subject, and I usually find the image flat and boring. For me, drawing is a discipline of the eyes; it is about seeing things honestly and feeling the brains influence over the eyes accuracy.” (Ian Ingram s show at Barry Friedman Ltd. in New York closed April 17.)

Ian Ingram now lives in Austin, but I first visited him in Santa Fe, at his studio at the top of Upper Canyon Road. On my initial visit, the first drawing of an interconnected 12-drawing series was under way. Seeing an artists drawings always puts me in closer contact with their unique internal workings. Drawing offers me connection with the contents of my own mind.

Given the artists boyish good looks and his virtuosic technique, the work – an epic, even magesterial achievement – could have developed a mawkish narcissism, Dorian Gray sans the tragedy. Further refinement of technique would have brought the drawing too close to perfection and left the image immaculately stillborn, without oxygen or rapture. The solution turned out for Ingram to be a radical increase in scale. At the increased scale the drawings ignore the boundaries of personal space.

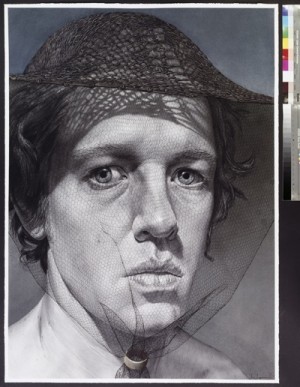

Ingrams face is rendered so large, with even its subtlest details so exaggerated, that one must be about ten feet away before one can escape a feeling of being thrust into unearned intimacy. In Pride of the Perdites Ingrams face masks an invented composite persona: a glad-hander with a cigarette and a slightly feminized Southern charm, his coin of the realm. Dont trust him. The saturation of gray makes the drawing heavy with guilt. The gold leaf on the ribbon is in the shape of the Louisiana Purchase, a memento which has interested other contemporary artists working on how histories of representation shape perception.

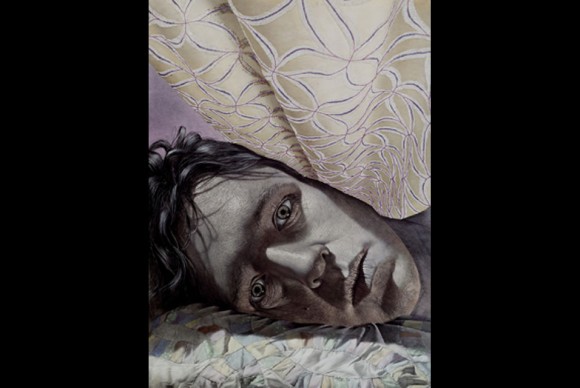

Visually Ingrams work, intermediary between peoples reluctance and inevitable contact with strangers, enters that defended area in which we usually only admit the closest of our intimates. His face, like a hologram projected by the mind, could be called “confrontational” if the mood were different.

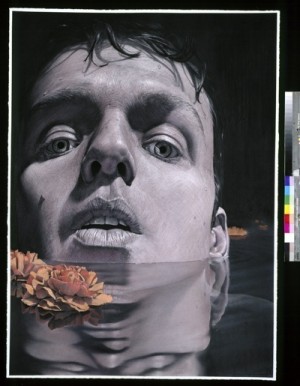

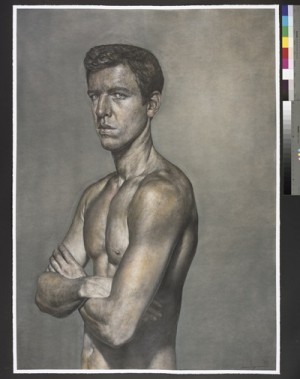

“This feeling of inconclusiveness,” Ingram points out about the drawing, Of Ash or Lead, “feeds into the title which I lifted directly from the definition of gray: The color of ash or lead. Not black and not white, only shades of gray.”

The head is tilted back trying to remain above water level while sweat trickles down his face to join the large pool of liquid below, blurring the separation between body and air and pointing to a more holistic truth: while everything is connected, it is not necessarily physically contained.

The artists calm gaze and usually impassive mouth calms the viewer. Ingram avers that “the blank page offers a vast potential for self-expression and my ego longs to fill it with false grandeur … Generally there are conflicts in my thoughts. Topics and issues have pros and cons (e.g., love brings attachment, but attachment leads to inevitable loss) and I usually have a great and exhausting internal battle about these.”

Could this imply Bridegroom Widow? offering a viewpoint of the marital state, as the replacement of independence with vulnerability. “One of the first things I remember saying,” the artist relates of spending 10 minutes alone with his wife after the wedding ceremony, was, I am going to miss you. ”

Ingram is a mapmaker of his face with a particular specialization, topography. Topography is the precise recording of rising and falling contours. In each drawing, the face remains a fixed piece of human geography. The content that gives each one its narrative is equivalent to weather sweeping through, changing emotional moods, increasing and decreasing light, blowing in vast clouds and then, in the next drawing, sweeping them away, as a new emotional front approaches. Weather, that current thought, that personal crisis, that flash of fear, is not permanent.

The mapmaker has made of his face a revealing journey of incremental mortality with moments of recognition from our own experience.

(top photo: Ian Ingram (American, b. 1974), “The Wedding Quilt”, 2008. Charcoal, pastel, beeswax and beads on paper, 60 x 44 inches (152.4 x 111.8 cm))