Face of Our Time: The Passing Stranger Who Moves Us

It is often possible to see terrific photography exhibitions in San Francisco and Face of Our Time: Jim Goldberg, Daniel Schwartz, Zanele Muholi, Jacob Aue Sobol, Richard Misrach, at SFMOMA through October 16, is one of the best I have seen; an ode to new photography with its heart firmly related to its head and its eyeball as cold and clear as glare ice.

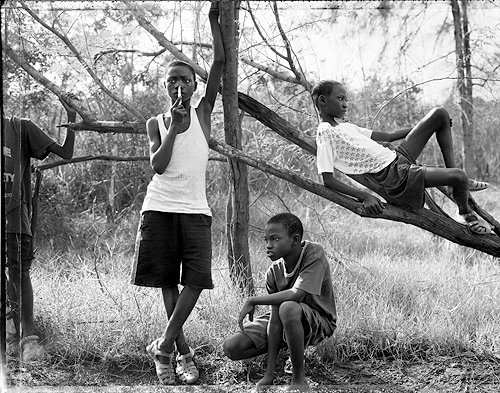

Jacob Aue Sobel in Face of Our Time

The documentary aspect of Face of Our Time deals in artists who have worked their subjects over time: Jim Goldberg, of San Francisco, is interested in refugees, especially African (and esp. Senegalese) refugees; Schwartz, a Magnum photographer, began working up a photo-story of the Silk Road after US-led war began in Afghanistan. Muholi is a South African lesbian for whom transgender experience in her peer group formed subject. Sobol, a Danish artist, deals in his personal relationship with his girlfriend, Sabine, and her family in Arctic Greenland in photos that are grimaces to regard. And Richard Misrach went on foot to record the graffito of human devastation around New Orleans after Katrina. Spray-painted messages of being barricaded, and effectively, abandoned. Powerful.

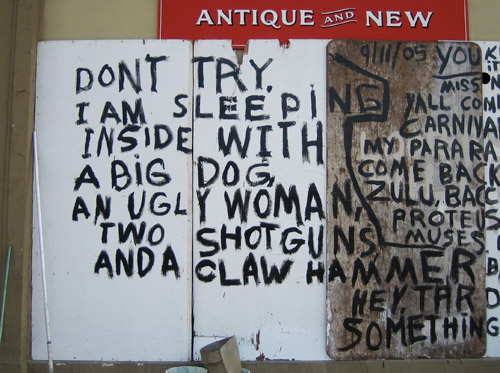

Richard Misrach, in Face of Our Time

I found myself first at SFMOMA”s third-floor mezzanine, confronted by two super-scaled Jim Goldberg photographs on which he had written in pencil some narrative text, a meandering print that followed the angles of the photograph like a child’s game. The bleached blocks of sky, grayish sea, called attention to the figure, a black man walking a goat through tide, about as poetic a figure as a photograph can capture imaginally through freight-of-circumstance.

“Open See” the title of the body of work that these photographs come from, deals in how a person, a Goldberg subject, described a desire to be elsewhere, in another condition, free. “Open,” connoting both aperture and democracy, “See,” a figure of speech meaning “understand?”

Yet “See?” as interrogation here is also “See” as imperative. Look! See! For Goldberg’s spot-on method of centering a subject in a frame creates a strange power between foreground and ancillary. Composition zooms you without rope into life, this life, their life.

“Poaching,” (featured image) finds three young men, one sitting in a tree, two homies to his left and right (the left-hand guy with steel blade), and me on-looking, stunned. Not only because these three lithe boys, were, are up to violence against wild things, they’re wild things themselves. But not anything like what “wild” means heretofore. “Wild,” synonym for abandoned in derelict society that has left these youths to fend for themselves like so. What you believed before in face of this photograph becomes stupendously unimportant, for their frozen presence is what is up, a frontalism that temporarily makes the case against the “cause,” suggests a new cause. Silent. Insolent. Confused. All of which becomes true, in the viewer.

Goldberg turns out humanist documents which are ineluctable.

Daniel Schwartz in Face of Our Time

Against this, in the second room, no less a photography genie than the Swiss Daniel Schwartz offered a place to stand (watching) that felt less vulnerable and exposed. For while these are beautiful photographs, their appearance as photographs, tremendously organized square-riddles, remains persistent. Schwartz is as Eisenstein to Goldberg’s Truffaut. The frame is made through bodies parting. The eyes of the woman behind the chador, the grid of her eye slots, are code for what else you can see that she is either blocking, or peripheral to.

Given how long I spent in the first two rooms, with these first two photographers, I had the sense on entering the next three of surfeit, not because of shortcomings in them as much as a feeling overcome these authors had evoked in me. As to Richard Misrach New Orleans images, I had to take them in a second; and finally saw how, for Misrach, these pictures of human-made signs fit formally into his prior work, allowing him to capture without the bodies of people the sense of an ongoing aura of places absent humans, which has characterized his environmental documents of Salton Sea, and the diffuse, remote blues of San Francisco Bay.

Zanele Muholi, in Face of Our Time

Daniel Aue Sobel’s look at the Greeland family of his girlfriend Sabine. at the desolation of their lives, marked this series out as a document of cold and faraway.

And Zanele Muholi’s work, elegant spare portraits of queer and transgendered women in South Africa, offered “Face” as a face, multiple faces, in essence daring the camera: “Being”? “Identity?” “Appearance?”

A tremendous show that calls out SFMOMA as the masterful museum for photography it has been, and is.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Through October 16.