Creative Santa Fe: Coals to Newcastle?

Four speakers for Creative Santa Fe’s inaugural “Imagined Futures” IF event, told a New Mexico History Museum auditorium full house on Saturday that:

Tourist towns are “brands.”

Attention to historic architecture can make a place a mecca.

Affordable housing for artists can retrofit vacant building stock, and is desirable. (image: Artspace affordable housing in Patchogue, NY)

Yes. So: what’s new?

The question goes ultimately to whether this new-old nonprofit called Creative Santa Fe, with a seven-year existence and a much more recent makeover with a five-person staff, will be true to its promise of “new ideas and tangible outcomes.” Those were the words of CSF’s chairman of the board Bill Miller, in opening remarks Saturday. By the new-ideas standard, Saturday was not an object lesson in how-to revitalize culture with new ideas, but an occasion in which three of four speakers essentially described their own cities’ adapting ideas that Santa Fe could be said to lead in already.

Speaker Eddie Friel who ran a “destination marketing” firm for Glasgow, Scotland, took the lectern first. Friel offered that Glasgow, had gone from “cultural slum” to cultural city of Europe over a 20-year period.

Speaker Eddie Friel who ran a “destination marketing” firm for Glasgow, Scotland, took the lectern first. Friel offered that Glasgow, had gone from “cultural slum” to cultural city of Europe over a 20-year period.

Glasgow, said Friel, had become an “event-led” city, where “point of entry” jobs dependent on tourism had ensued. Nurturing the buildings and style of Glasgow’s famous 20th-century architect, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, was a strategy of cultural regeneration, Friel said. One mark of Glasgow’s cultural success: Airport arrivals went from 700,000 in 1983 to 8 million in 2003, said Friel.

An obvious observation is that Santa Fe lacks a major airport that would permit parallel “point-of-entry” job growth. Further, Santa Fe’s historic architecture was a cornerstone of tourism strategy, beginning around 1928. Preservation is an area in which Santa Fe has led architecture for decades; indeed, preservation and adaptable re-use have become such a way of life here that Frank Gehry once joked that were he to design a building for Santa Fe (a rumor whose falsity was early established), he would need to use brown glass.

Buffalo, NY, likewise cites historic architecture as cultural generator. Mary Roberts, who heads the Martin House Restoration Corporation in Buffalo, New York, next took the stage to discuss the MHRC’s $50 million architectural restoration project on a Frank Lloyd Wright building complex in Buffalo. She said the outcome will be 198 jobs for an $8 million annual payroll, and a total $17.6 million annual economic impact. Yet, cultural economy notwithstanding, Buffalo’s economic woes persist.

“Ouch!” reads a 2010 headline of a population report from Buffalo Rising – which relates: “Population estimates for 2010 and 2020 prepared by the Mayor’s Office of Strategic Planning based on a straight-line extrapolation of the 1990-2000 trend suggest that the city’s population may continue to decline to 250,000 or lower before growth resumes.”

These numbers mark a 10.7 percent population decline in the last decade, and a 50% drop in population, per the US Census, since 1970, reflecting decimation in the steel manufacturing sector, and commerce on the Great Lakes.

Such data – not difficult to find – make Creative Santa Fe’s incipient strategy very difficult to follow on the logic of straight-up economic analysis.

Even overlooking the lack of useful detail from program speakers, the simple fact that CSF’s first event couldn’t stick with the program raised a caution. It was 6:50 p.m. – just shy of two hours of lecture – when the final speaker’s presentation ended. While the printed program billed a panel discussion and presumably, a short q-and-a with audience, neither occurred. (Not a good augur for conference staff’s experience.)

The pertinence of the would-be examples continued to escape me, through Louis Grachos’s summary of his work as director (since 2003) at the Albright-Knox Gallery of Art.

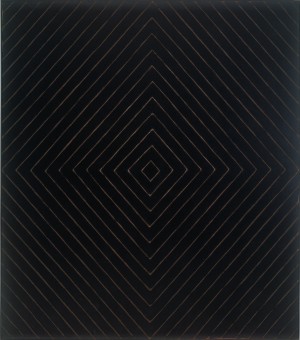

Part of the Albright-Knox collection: Clyfford Still (American, 1904–1980), 1957-D No. 1, 1957. Oil on canvas; support: 113 x 159 in. Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. Gift of Seymour H. Knox, Jr., 1959. Photograph: Tom Loonan © Clyfford Still Estate

Grachos, who is a CSF board member and directed SITE Santa Fe until 2003, gave an example of museums going outside institutional boundaries – such as when French tightrope walker Didier Pasquette navigated between the towers of Buffalo’s Liberty building in 2010.

The final speaker: Architect Matthew Meier, dealt with artists’ affordable housing, presumably as a key rung of CSF’s new mission to invigorate creative economy here. But incomprehensibly, we learned nothing about the outcome of two days of artists’ and funders’ community meetings in Meier’s presentation. Artspace as a nonprofit operates with significant foundation funding; according to its schedule, it charges $12,500 for a two-day visit to a community outside its home state of Minnesota. Artist market surveys and arts’ organization surveys respectively cost $30,000 and $45,000.

Meier presented on live/work spaces from El Paso, Texas; New York, NY; Patchogue, NY; and Buffalo, NY. Three of the four relied on first identifying vacant building stock in cities for retrofits. In Patchogue, Artspace found a site for a new building. Meier showed maps and interior shots, but never got to specifics such as: what are building costs? What defines “affordable?” (Case-by-case; or a formula?); What about zoning and overlay issues?

Meier told Conrad Skinner after the event that in the community meetings here, participants said the Railyard would be the logical site of affordable housing. (Begging the question of Don Wiviott’s Live/Work Artyard lofts, which had dedicated several affordable units for artists, in foreclosure and in the sights of lawsuits.) The Albuquerque Journal editorialized a year ago that the Artyard spaces at the Railyard might have worked out, albeit at $500k plus price points.

“But given that Wiviott and his partners seem to have run out of money to follow through on the project, we may never find out whether Santa Feans are really ready to embrace the live-work concept — particularly at the prices mentioned in the latest ArtYard court action, more than a half-million bucks per unit,” the Journal wrote.

If Creative Santa Fe is getting behind affordable housing, is it because there has been a needs assessment surveying artists? And will CSF be lobbying the city for policy changes, simultaneously?

The Creative Santa Fe website has a long list of initiatives – production of an Imagined Futures IF festival, an IF conference, IF residencies and an IF online magazine. But as the mission drift exemplified by its first event comes into strange focus, this first event had a patronizing flavor, not mitigated by the announcement that next up for the Santa Fe series is a session on “missing links” from Canyon Road to the Railyard, called “Santa Fe Ground Up.” In terms of attracting the young people whose leaving town is widely considered problematic, I don’t know whether the organizers just overlooked that this first Santa Fe series event was also the day of commencement from Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Not a single person under 30 appeared to be in the building.

The question for Creative Santa Fe may not be IF, but why?