Hospitality Channel: Bali (detail), 2013, By Andrew Witrak (American). Single channel video. Running time: 3 minutes looped. Courtesy of the Artist.

What Is Contemporary Art Actually Mapping?

A map, which is usually thought of as a fixed, 2-D object, has become something else entirely in the information age—an ever-changing dataset subject to revisions. Author Rebecca Solnit, in her book Infinite City: a San Francisco Atlas, maps the city by butterfly migrations and drag queen sightings rather than by street names and the atlases of the old Mapsco. Solnit clearly reminds us that a map is “an arbitrary selection of information”—a fact often forgotten, but which has been true since mapping’s inception.

Contemporary thinkers James Corner and Peter Hall, also consider mapping to be a process that remains perpetually incomplete. And, since “a map” can now live in virtual space exclusively, it can also endlessly change and assemble information beyond basic geography (Wiki-style). There’s an “associative” element to mapping between a “given set” that is “the domain” and elements of a second set that is “the range.”

Hall, a leading design professor now heading the design department at Griffith University Queensland College of Art, defines mapping as “the process that precedes the map; the gathering of information, whereas the map tends to describe the finished moment of the project.” In his 2010 lecture “The Art of Mapping” at University of Texas at Austin (his previous post), Hall quotes landscape architect and urban theorist Corner, who defines mapping as “the digging, finding and exposing; relating, connecting and structuring of information.” (Click on the red type to see Hall’s complete “The Art of Mapping” lecture.)

Mapping piqued my interest when I noticed a trend toward place-based conversations in contemporary art. Also, I find mapping an apt metaphor for contemporary culture—at a time in which expanded cultural views and globalization seem to be simultaneously collapsing into hyperlocalism and a population of self-proclaiming “locavores.” As I embark on my master’s degree in Curatorial Practice at the California College of the Arts in San Francisco, I foresee that the concept of mapping could (and perhaps should) help shape 21st-century curatorial dialogue.

Independent curator and educator Glen Helfand’s recent three-part exhibition series, Proximities, at the Asian Art Museum addresses the perception of Asia, as if an exercise in mapping.

Helfand assembled an ethnically diverse group of contemporary Bay Area artists for the exhibition, including Asian-Americans and non-Asian artists. The first exhibition titled What Time is it There? exposes notions of place, but not in a traditional sense—fantastical places and personal narratives are explored.

American born Tucker Nichols’s idea of Asia, as shown through his piece Untitled (GR1301), arose from his experience with his mother’s antique collection and his work at the Asia Society in New York as a young adult. The culmination of Nichols’ piece is a series of hundreds of quickly brushed paintings of vases. These “cultural portals” (as described by fellow exhibiting artist Ala Ebtekar) into Asia can be identified throughout the United States and noticeably in the Bay Area.

Helfand’s curatorial approach to Proximities “re-maps” Asia for the viewer—metaphorically redrawing the boundaries of Asian art as something that also exists and is produced in the United States. In his words, “I was initially inspired by Raymond Roussel’s 1910 surrealist novel, Impressions of Africa, which revels in the notion of the imagined place through a formalized lens. In Proximities, we are viewing the concept of “Asia” from California, in a museum that is very much a constructed presentation of culture and an institution beset with unavoidable cultural baggage.”

The context of the Asian Art Museum is that it is a labyrinth of galleries labeled by the country of origin for what were once exotic, but now familiar appearing objects. Helfand’s contemporary view of Asia opposes the popularized aesthetic of each continent as on display in the museum. Within the concept of mapping, therefore, Proximities updates the domain of Asia by allowing a wider population to be part of what Asian is.

In the Proximities I exhibition, the viewer experiences a dissolve of Asian culture-as-other by relating to the personal narratives of the participating artists.

In a different discipline and place but in a similar vein, University of Utah English professor Paisley Rekdal proposed a place-based narrative mapping project with her students, soon-to-be available to a global audience via the Internet. The objective is to reveal a more complete story, or map, of Salt Lake City by collecting the personal histories of the university’s students. The audio of the students’ narratives will create a new map of Salt Lake City. Another example like this is Murmur, which started in Scotland.

In reference to contemporary art, two important concepts emerge here: the map as a postmodern construct and the ability of the digital infrastructure to support a fluctuating “range” of data based on the ever-changing process of mapping.

As a curatorial model, mapping allows contemporary curators to redefine the boundaries of museums by reconstituting the range of art history to a new, and perhaps also virtual, domain. Finally, mapping, as a new structure for curating, offers a design solution for another organizational problem in the arts–which is the interactivity of the public with the institution (i.e. museum or art center). Although mapping, as I have explored it here, is a largely unidentified trend in contemporary art, I foresee it as having significant ramifications for the art object’s viability in the increasingly technological future.

Antioch Creek, 2008, by Larry Sultan (American, 1946–2009). Chromogenic print, edition of 9. H. 40 5/8 x W. 49 3/4 in. © Estate of Larry Sultan. Courtesy of the Stephen Wirtz Gallery and Pier 24.

Cocktail umbrellas, styrofoam, by by Andrew Witrak (American). Courtesy of the Artist.

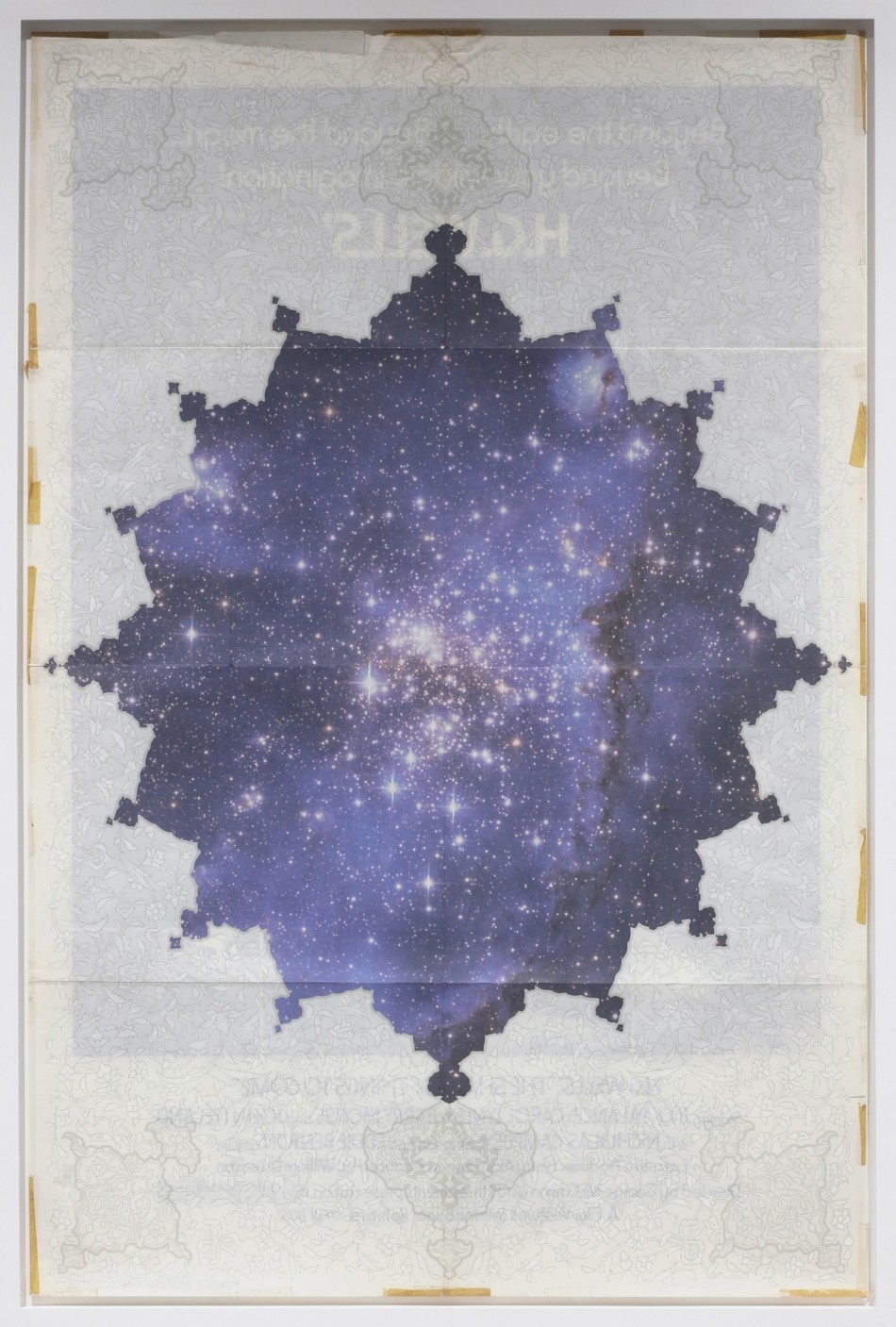

The Shape of Things to Come, 2012, by Ala Ebtekar (American). Acrylic on archival pigment print on found poster. Courtesy of Paule Anglim Gallery. Photo: Wilfred J Jones.

Hospitality Channel: Bali (detail), 2013, By Andrew Witrak (American). Single channel video. Running time: 3 minutes looped. Courtesy of the Artist.