Becoming Van Gogh at the Denver Art Museum

Becoming Van Gogh might be Dr. Timothy J. Standring’s defining exhibition. Standring is the Gates Foundation Curator of Painting and Sculpture at the Denver Art Museum and has curated nine exhibitions there since 1989, including Inspiring Impressionism, El Greco to Picasso from the Phillips Collection and Impressionism: Paintings Collected by European Museums.

Becoming Van Gogh examines the evolution of the largely self-taught artist through more than 70 paintings and drawings, most by Van Gogh, but also key works by artists to whom he responded or reacted: William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Jean Francois Millet, Adolphe Monticelli, Paul Signac, Emile Bernard and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. The DAM is the only venue for the exhibition, which brings together loans from more than 60 public and private collections in Europe and North America (the museum doesn’t own a Van Gogh). The exhibition illustrates Van Gogh’s foray into mastering draftsmanship, understanding materials and techniques, learning to incorporate color theory and exploring his own eye for color by combing threads of yarn. Focusing on the artist’s personal growth and progression, the exhibition tells a compelling narrative of the development of Van Gogh—the artist.

Standring said Van Gogh was an underdog. “A Rocky Balboa of art, who started off after four careers and was determined and disciplined to become an artist.”

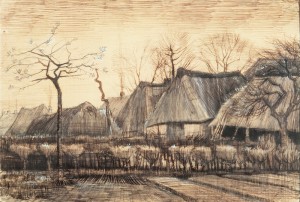

Those careers were: assistant art dealer, working in a bookstore, substitute teacher and evangelical minister. At 27, Van Gogh dedicated his life to making art and taught himself how to draw. In 10 short years he sampled a smorgasbord of avant-garde ideas and styles, from the lighter color palette of the Impressionists to Neo-Impressionist short brushstrokes to flat areas of color and strong outlines found in Japanese prints. Through his own personal and creative inclinations he created a new way to paint. His development wasn’t the result of emotional paroxysms of creativity—it was measured. He focused on one element at a time in logical order—drawing, line, color, perspective and brushstroke.

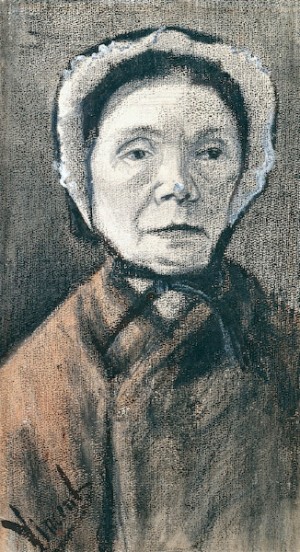

“Just let me be myself—and express severe, rough, yet true things with rough workmanship,” Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo. In his early work he wanted to channel his spiritual convictions into art, to create what he called visual sermons that express a moralizing message. His early preferred subject matter were objects old and tattered—worn shoes, peasants and people from the streets. He was devoted to the figure and capturing the opposite of Bouguereau—not the beauty found in unadorned nature, but the sorrow of broken souls.

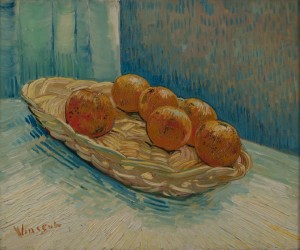

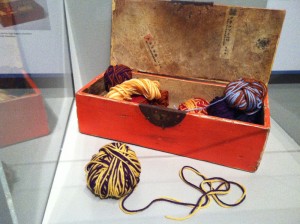

Early on he favored the dark browns and grays of Dutch painters, seen in what is considered his first masterpiece, The Potato Eaters, finished in 1885, the same year his father died and Van Gogh visited the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Van Gogh began to embrace the emotive potential of color inspired by the Old Masters he saw there—Rembrandt, Rubens and Frans Hals. Van Gogh switched from drawing to painting, concentrating his efforts on mastering color, which he did by winding different colors of yarn together, keeping the colors separate, just as he did on the canvas using short, side-by-side brushstrokes of unmixed paint.

He again wrote to his brother Theo who lived in Paris: “As you can see, I am immersing myself in color—I’ve held back from that until now; and I don’t regret it.”

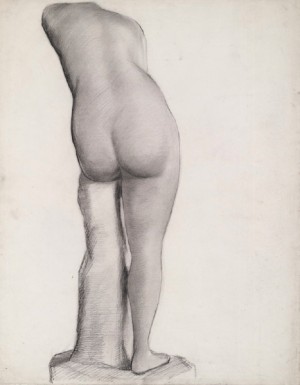

In 1886, Van Gogh surprised Theo by arriving in Paris where he continued his figure studies at the studio of Fernand Cormon, discovered Monticelli and pointillism and where he painted 20 self-portraits while becoming enamored of Impressionist techniques, coloration and Japonisms bold designs, flat areas of color and elegant and simple lines. “I envy the Japanese,” he wrote. “The extreme clarity that everything in their work has.”

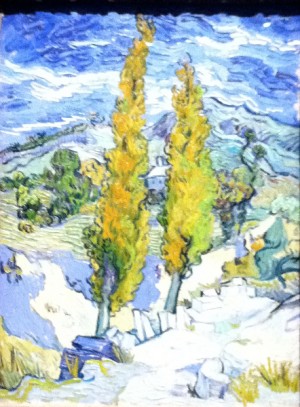

By 1888 Van Gogh had moved to Provence.

“This part of the world seems to me as beautiful as Japan for the clearness of the atmosphere and the gay color effects. The stretches of water make patches of a beautiful emerald and a rich blue in the landscapes, as we see it in the Japanese prints,” he wrote.

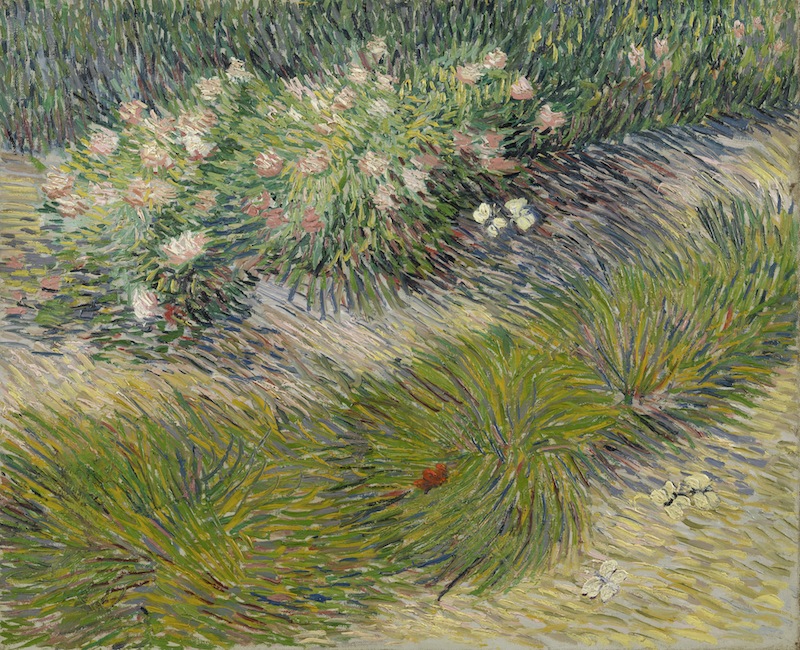

It was in Arles that he worked side-by-side with Paul Gauguin for nine weeks during autumn before having a psychotic or metabolic episode that resulted in part of his ear being cut off, some say by Gauguin’s sword, others that Van Gogh himself sliced it off with a razor blade. Van Gogh was hospitalized, but continued to paint from the gardens of the asylum at Saint Paul-do-Mausole.

By July 27, 1890, Van Gogh was dead, either the victim of a self-inflicted gunshot or an accident in a field near the village of Auvers-sur-Oise. Inside a decade he had created 864 paintings and almost 1,200 drawings and prints that survive today. He sold only one (to his brother Theo) during his lifetime: The Red Vineyard at Arles.

Standring and his collaborator, Louis van Tilborgh, the senior researcher of paintings at the Van Gogh Museum, have developed an exhibition that explores the labyrinth-like journey Van Gogh took, forged by his highly organized mind and unpredictable creative impulses. Whether drawing or painting, it appears that Van Gogh understood when he succeeded and knew also when he failed. He was ever focused on the figure, yet is known for his landscapes. This exhibition pivots around the elements that came together in a short decade for the artist and punctuates what Van Gogh himself wrote.

“For the great doesn’t happen through impulse alone, and is a successor of little things that are brought together.”